|

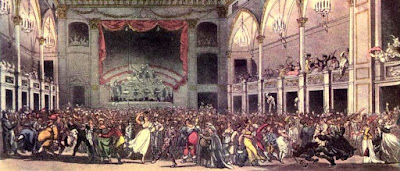

Masquerade at the Pantheon (cropped)

from The Microcosm of London Vol 2 (1808-10) |

A masquerade is a valuable plot device for a historical romance writer. There is no end to the scenarios that could arise when your characters’ identities are disguised. When writing the first draft

of

A Reason for Romance (

The Merry Romances #2), I saw how I could use a masquerade to take the story where I wanted it to go. Questions immediately arose in my mind. I knew that masquerades were very popular in the 18th century, but did they still have masquerades in 1810? Were they as I imagined them? What sort of costumes did they wear, and did they always wear masks?

Public masquerades

According to the Picture of London (1810), public masquerades took place at the Argyle Rooms, the Opera House and the Pantheon. It wrote:

The Fashionable Institution in Argyle-street embraces the amusements of masquerades, concerts, vocal and instrumental, &c.1

In the diary of the exhibitions and amusements of London for the month of January it stated:

N.B. In the course of this and the ensuing five months, masquerades are occasionally held at the Opera-house, and the Pantheon, always previously advertised in the newspapers, admission 10s 6d, 1l 1s and 2l 2s and dresses may be hired at the masquerade warehouses, from 5s to 2l 2s each.1

The plate of

Masquerade at the Pantheon (shown cropped at the top of this post and in full under 'A masquerade in

The Sylph' below) accompanied a chapter on the Pantheon in the

Microcosm of London. It said:

Since the Pantheon was rebuilt, it has been principally used for exhibitions, and occasionally for masquerades, of which the plate is a very spirited representation. It is composed, as these scenes usually are, of a motley crowd of peers and pickpockets, honourables and dishonourables, Jew brokers and demireps, quidnuncs and quack doctors.2

A masquerade at

the Argyll Rooms was advertised in

The Times for 31 May 1810:

Masquerade, Argyle Rooms. – By Permission of the Right Hon. the Lord Chamberlain. – S. Slade most respectfully informs the Nobility, Gentry, and his Friends in general, that his BENEFIT MASQUED BALL will take place on Wednesday, the 6th of June. Gentlemens Tickets 1l 11s 6d Ladies Tickets 1l 1s; to include Refreshments, Supper, old Port, Sherry, Madeira, and Claret, to be had at the Office, Little Argyle-street. To prevent the intrusion of improper persons, no ticket will be issued, unless the name and address is left at this Office.3

|

Masquerade, Argyll Rooms

Print by T Lane Published by George Hunt (1826) © British Museum |

Private masquerades

One was a breakfast masquerade held at the house of Lady Buckinghamshire on 22 May 1810. The guests had been invited to come in fancy dress but the ambassador and his host, Sir Gore Ouseley, did not. The ambassador noted that the costumes included a lady’s maid, a sailor, and a Roman empress, and numerous Iranians, Turks and Indians. He commented that one Iranian ‘wore a false beard made from the hair of a cat or a goat.’ I like to use real events in my stories where possible, and so in A Reason for Romance, my heroine Georgiana attends this breakfast masquerade along with the Persian ambassador and some 500 others.

He attended another masquerade – this time a ball – at Mrs Chichester’s house on 18 June. Sir Gore Ouseley pretended he was not going but actually dressed up as a Persian and tried to fool the ambassador.

At another masquerade in June, the ambassador was approached by Lady William Gordon, who was then unknown to him, disguised as a priest.

|

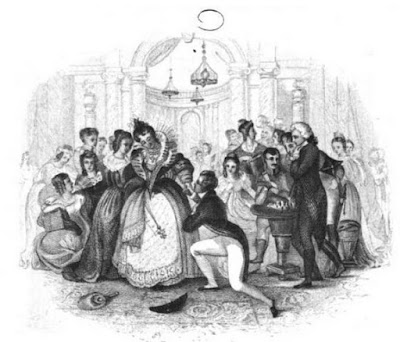

Masquerading by Thomas Rowlandson (30/08/1811)

from the Metropolitan Museum DP881828 |

A masquerade in The Sylph

Judging by the number of contemporary novels that include masquerades, it would appear to have been generally accepted that a person’s identity could be successfully hidden by their costume. The accounts often include details of the characters and costumes worn.

The Sylph by

Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, was published in 1778. The heroine, Julia, Lady Stanley, attends a masquerade at the Pantheon. Here she meets in person the Sylph, a man who has been acting as her guardian angel, giving her advice by letter. The author gives us a detailed description of what the Sylph was wearing:

I will describe his dress: his figure in itself seems the most perfect I ever saw; the finest harmony of shape; a waistcoat and breeches of silver tissue, exactly fitted to his body; buskins of the same, fringed, &c.; a blue silk mantle depending from one shoulder, to which it was secured by a diamond epaulette, falling in beautiful folds upon the ground; this robe was starred all over with plated silver, which had a most brilliant effect; on each shoulder was placed a transparent wing of painted gauze, which looked like peacocks feathers; a cap, suitable to the whole dress, which was certainly the most elegant and best contrived that can be imagined. I gazed on him with the most perfect admiration. Ah! how I longed to see his face, which the envious mask concealed. His hair hung in sportive ringlets; and just carelessly restrained from wandering too far by a white ribband.4

This idea that a costume gave a sense of anonymity is further reinforced when Julia leaves the masquerade in the company, so she thinks, of her husband:

I had taken off my mask, as it was very warm; he still kept his on, and talked in the same kind of voice he practised at the masquerade. He paid me most profuse compliments on the beauty of my dress, and, throwing his arms round my waist, congratulated himself on possessing such an angel, at the same time kissing my face and bosom with such a strange kind of eagerness as made me suppose he was intoxicated; and, under that idea, being very desirous of disengaging myself from his arms, I struggled to get away from him. He pressed me to go to bed; and, in short, his behaviour was unaccountable: at last, on my persisting to intreat him to let me go, he blew out one of the candles. I then used all my force, and burst from him, and at that instant his mask gave way; and in the dress of my husband, (Oh, Louisa! judge, if you can, of my terror) I beheld that villain Lord Biddulph.4

|

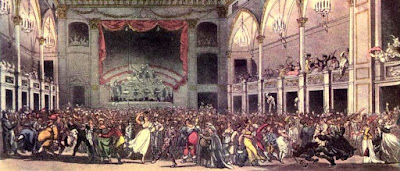

| Masquerade at the Pantheon from The Microcosm of London Vol 2 (1808-10) |

A masquerade in Cecilia

Fanny Burney’s

Cecilia was published in 1782. Burney’s description of a masquerade attended by her heroine Cecilia gives us details of some of the costumes people wore:

Dominos of no character, and fancy dresses of no meaning, made, as is usual at such meetings, the general herd of the company: for the rest, the men were Spaniards, chimney-sweepers, Turks, watchmen, conjurers, and old women; and the ladies, shepherdesses, orange girls, Circassians, gipseys, haymakers, and sultanas.5

Burney also mentions a Minerva, a Don Devil and a Harlequin.

A masquerade in Belinda

Belinda by Maria Edgeworth was published in 1801. Edgeworth describes how Belinda and her hostess, Lady Delacour, are to go to a masquerade.

Lady Delacour burst into the room, exclaiming, in a tone of gaiety, “Tragedy or comedy, Belinda? The masquerade dresses are come.”6

Lady Delacour chooses tragedy but then changes her mind and insists that they swap dresses. She assures Belinda: ‘Not a human being will find us out at the masquerade.’6

The disguise is so good that Lady Delacour’s admirer, Clarence Hervey, mistakes Belinda for Lady Delacour, and Belinda overhears a conversation not intended for her ears which includes derogatory comments about her aunt and herself.

Edgeworth also describes the elaborate costume of a serpent that Mr Hervey had planned to wear:

The first person they saw, when they went into the drawing-room at Lady Singleton’s, was this very Clarence Hervey, who was not in a masquerade dress. He had laid a wager with one of his acquaintance, that he could perform the part of the serpent, such as he is seen in Fuseli’s well-known picture. For this purpose he had exerted much ingenuity in the invention and execution of a length of coiled skin, which he manoeuvred with great dexterity, by means of internal wires; his grand difficulty had been to manufacture the rays that were to come from his eyes. He had contrived a set of phosphoric rays, which he was certain would charm all the fair daughters of Eve. He forgot, it seems, that phosphorus could not well be seen by candlelight. When he was just equipped as a serpent, his rays set fire to part of his envelope, and it was with the greatest difficulty that he was extricated. He escaped unhurt, but his serpent’s skin was utterly consumed; nothing remained but the melancholy spectacle of its skeleton.6

Edgeworth notes that:

After a recital of his misfortune had entertained the company, and after the muses had performed their parts to the satisfaction of the audience and their own, the conversation ceased to be supported in masquerade character; muses and harlequins, gipsies and Cleopatras, began to talk of their private affairs, and of the news and the scandal of the day.6

On arriving at the Pantheon, Lady Delacourt gives Belinda the following advice:

You have nothing to fear from me, and everything to hope from yourself, if you will only dry up your tears, keep on your mask, and take my advice.6

Later, Edgeworth refers to another masquerade costume:

Lady Delacour … returned, dressed in the character of Queen Elizabeth, in which she had once appeared at a masquerade, with a large ruff, and all the costume of the times.6

|

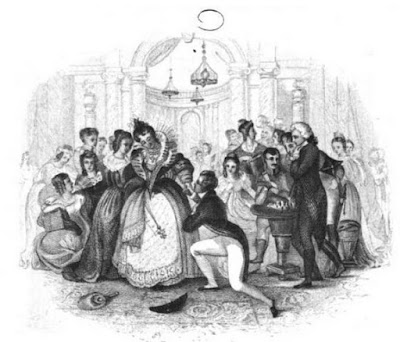

| Illustration from Belinda by Maria Edgeworth - 1850 edition |

Costumes at Vauxhall in 1787

Further suggestions of the costumes people wore can be gleaned from the description of the masqued ball in Vauxhall Gardens in May 1787 which was reported in

The Times. The costumes of note included ‘a lady who professed herself eight months advanced in pregnancy’

7 which was judged to be an excellent character, but a poor disguise as she was unmasked. She was accompanied by a nurse. There was also a wild Irishman, a wooden-legged Harlequin, a noisy watchman, a woman selling primroses, a Punch, young Astley as half Beau and half Belle, a Highland lad and lassie, the character of a porter from the comic opera

The Duenna who ‘asked no more than nature craved’ (a line from

The Duenna which was written by

Richard Brinsley Sheridan) and a cobbler, together with an assortment of cricketers, haymakers, flower girls and vestal virgins.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(2) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 2 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(3) From The Times, 31 May 1810.

(4) From Cavendish, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, The Sylph (1778).

(5) From Burney, Fanny, Cecilia or Memoirs of an Heiress (1782).

(6) From Edgeworth, Maria, Belinda (1801).

(7) From The Times, 18 May 1787.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 2 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Burney, Fanny, Cecilia or Memoirs of an Heiress (1782)

Cavendish, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, The Sylph (1778)

Edgeworth, Maria, Belinda (1802)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Hassan Khan, Mirza Abul, A Persian at the Court of King George 1809-10, edited by Margaret Morris Cloake (1988)

The Times online archive