‘Silly Billy’ is a common nickname for someone who behaves foolishly, and is particularly appropriate if their name happens to be William. The nickname appears to originate in the 18th century, but I have found three different royal Williams who earned it: Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester; King William IV; and Prince William of Orange. But which one was the original ‘Silly Billy’?

Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (1776-1834)

|

| Prince William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany by John Watkins (1827) |

The Duke of Gloucester was a cousin of George IV and was a very pompous man, who demanded great respect for his royal status. He was widely known for his lack of intelligence. As Captain Gronow records:

His Royal Highness, who was in the habit of saying very ludicrous things, asked one of his friends in the House of Lords, on the occasion when William IV assented to Lord Grey's Proposition to pass the Reform Bill ‘coute qui coute’, ‘Who is Silly Billy now?’ This was in allusion to the general opinion that was prevalent of the Royal Duke's weakness, and which had obtained for him the sobriquet of ‘Silly Billy’.1

Whilst confirming that the Duke knew that he was widely known as ‘Silly Billy’, this anecdote implies that he thought his cousin, William IV, was proving as great a fool as he by his political actions.

A Reformer’s Petition

|

| The Petition, advertised in The Satirist (1831) © The Trustees of the British Museum |

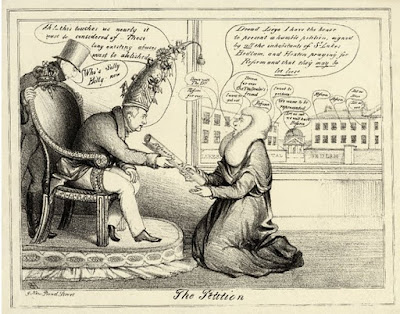

A contemporary cartoon from 1831 seems to support this. It depicts William IV sitting on a carved chair and wearing a fool’s cap. Kneeling in front of him is Brougham, presenting ‘A Reformer’s Petition’, with the words:

William IV, Duke of Clarence (1765-1837)“Dread Liege I have the honour to present a humble petition, signed by all the inhabitants of St Luke’s Bedlam, and Hoxton praying Reform and that they may be let loose.”The King says: “Ah! – this touches us nearly it must be considered of – These long existing abuses must be abolished.”Behind the king, the Duke of Gloucester, wearing a top hat, bends forward to say: “Who’s Silly Billy now?”2

|

| William IV From The History of the Life and Reign of William IV by Robert Huish (1837) |

Many sources suggest that the phrase ‘Silly Billy’ was originally coined for William IV. Plantagenet Somerset Fry’s book, Kings and Queens of England, suggests that he earned this nickname because, as a young man, he was very excitable and rather tactless. Evidence seems to suggest that his behaviour was very wild and ridiculous at times and that possibly he was afflicted with the same mental instability as his father, George III.

There is an anecdote in circulation that when William became king, his first remark to his Privy Council who were kneeling before him was “Who is ‘Silly Billy’ now?” but I have failed to find an original source for this and the documentary evidence seems to put the words into the mouth of the Duke of Gloucester rather than William IV as mentioned above.

“One of the silliest old gentlemen”

However, there is no doubt that William IV behaved, at times, in a very silly manner. Greville declared in his memoirs that King William’s

...ignorance, weakness, and levity put him in a miserable light, and prove him to be one of the silliest old gentlemen in his dominions; but I believe he is mad... and he reported that the King had made a number of speeches, so ridiculous and nonsensical, beyond all belief but to those who heard them, rambling from one subject to another, repeating the same thing over and over again, and altogether such a mass of confusion, trash and imbecility as made one laugh and blush at the same time. He goes on to say that: The Government and their people have now found out what a fool the King is…they find him rather shuffling and exceedingly silly.3Prince William of Orange (1792-1849)

A third William who lived during the Regency period and was not known for his wisdom was Prince William of Orange, who was briefly engaged to Princess Charlotte. Parissien describes him as:

a short and skinny and indecisive youth (and later in life a notoriously dull drunk) invariably known as ‘Silly Billy’.4

Prince William of Orange served on the Duke of Wellington’s staff in the British Army in the Peninsular War but here his nickname was ‘Slender Billy’, referring to his youth rather than his stupidity. He commanded the Dutch-Belgian forces under Wellington at the Battle of Waterloo, where he was injured, but although “not deficient in personal courage”, it is believed that his inexperience was responsible for errors which cost the lives of many men.

So who was the original ‘Silly Billy’?

All three Williams were known for their lack of wisdom, but I believe that the Duke of Gloucester was probably the original ‘Silly Billy’. Both in Gronow’s reminiscences and in the satirical cartoon, the Duke is acknowledged as ‘Silly Billy’.

However, Greville’s memoirs suggest that William IV deserved the nickname as much as the Duke by his increasingly eccentric behaviour. It is unsurprising that the nickname has become associated with William IV given the importance of his standing compared to his relatively unknown cousin.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

- Gronow, Captain, The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1900).

- The Petition, a satirical print (1831) © British Museum.

- Greville, Charles CF, The Greville Memoirs, edited by Henry Reeve (1874).

- Parissien, Steven, George IV, The Grand Entertainment (2001).

Fry, Plantagenet Somerset, The Kings & Queens of England & Scotland, (1990)

Greville, Charles CF, The Greville Memoirs, edited by Henry Reeve (1874)

Gronow, Captain, The Reminiscences and Recollections of Captain Gronow (1900)

Hibbert, Christopher, George IV (1972, 1973)

Huish, Robert, The History of the Life and Reign of William IV (1837)

Parissien, Steven, George IV, The Grand Entertainment (2001)

Purdue, AW, William Frederick, Prince, second Duke of Gloucester and Edinburgh (1776-1834), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, online edition (2009)