|

Princess Caroline of Brunswick by Sir Thomas Lawrence (c1804)

© National Portrait Gallery, London

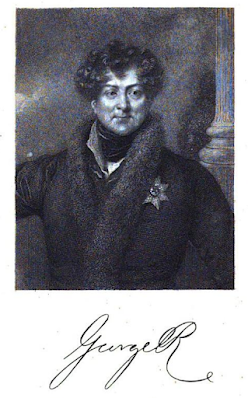

George IV when Prince of Wales by John Hoppner (1792)

© The Wallace Collection |

Resigned to an arranged marriage

George, Prince of Wales, and

Princess Caroline of Brunswick were married on 8 April 1795. Although they were first cousins, the couple had not met before the marriage was arranged. Neither the Prince of Wales nor the Princess Caroline wanted the match, but they both agreed to it.

British law had severely restricted George’s choice of bride.

1 His secret marriage to his mistress,

Mrs Fitzherbert, was not legal, and, desperate for money, the Prince had agreed to marry his father’s choice of bride.

But George was not the only one to suffer from this arranged marriage. After accepting the Prince’s proposal, Princess Caroline wrote to a friend:

I am indifferent to my marriage, but not averse to it; I think I shall be happy, but I fear my joy will not be enthusiastic. The man of my choice I am debarred from possessing, and I resign myself to my destiny.2

An uncouth bride?

Lord Malmesbury was sent to Brunswick to present the Prince’s proposal and describes his first impressions of Caroline in his diary:

Pretty face — not expressive of softness — her figure not graceful — fine eyes — good hand — tolerable teeth, but going — fair hair and light eye-brows, good bust — short.3

|

Lord Malmesbury

from Diaries and Correspondence of James Harris,

First Earl of Malmesbury, Volume III (1834) |

He goes on to record his reservations about Caroline’s suitability as a bride for the Prince:

Princess Caroline very missish at supper. I much fear these habits are irrecoverably rooted in her — she is naturally curious, and a gossip.3

He was obliged to caution her “to think always before she speaks” and to make improvements in her personal hygiene.3 He was particularly revolted when she had a tooth drawn and had it sent to him as a gift!

But he was not blind to her good points, noting that “she improves very much on closer acquaintance - cheerful, and loves laughing” and that she “understands a joke and can make one.”3

Lord Malmesbury remained very concerned about the suitability of the match:

We regret the apparent facility of the Princess Caroline's character—her want of reflection and substance— agree that with a steady man she would do vastly well, but with one of a different description, there are great risks.3

First impressions

Neither party was expecting a love match, but Princess Caroline, at least at the start, was hopeful of a good relationship with her cousin. She wrote to her friend:

I esteem and respect my intended husband, and I hope for great kindness and attention ... I shall strive to render my husband happy.2

Lord Malmesbury records their first meeting:

I, according to the established etiquette, introduced ... the Princess Caroline to him. She very properly ... attempted to kneel to him. He raised her (gracefully enough), and embraced her, said barely one word, turned round, retired to a distant part of the apartment, and calling me to him, said, "Harris, I am not well; pray get me a glass of brandy."3

Caroline was unimpressed. When Lord Malmesbury rejoined her she exclaimed in French, asking if the Prince was always like that and declaring that she found him very fat and nothing like as handsome as his portrait.

Wronged wife

When Princess Caroline arrived in England she hoped for “great kindness and attention.” She received neither.

The King was effusive in welcoming her, but

the Queen was cold and her future husband indifferent. George had never wanted the marriage apart from as a way to secure funds, and he was heavily influenced by his new mistress,

Frances, Countess of Jersey, whom he heartlessly appointed as a Lady of the Bedchamber for his new wife.

From the first moment of setting foot on English soil, Princess Caroline was subject to Lady Jersey’s spite. The Prince made no secret of the fact that Caroline was his wife in name only. When she unwisely revealed her previous attachment, Lady Jersey had no scruples in laying this before the Prince and poisoning his mind against his new wife.

Separation

The Prince of Wales’ dislike grew. He wanted to divorce his wife, but the King was emphatically against it. A separation, however, was unavoidable.

In a letter from the Prince of Wales to his wife dated 30 April 1796, the Prince stated that:

Our inclinations are not in our power; nor should either of us be held answerable to the other, because nature has not made us suitable to each other. Tranquil and comfortable society is, however, in our power; let our intercourse, therefore, be restricted to that.4

Caroline’s reply was also printed, saying that his letter “merely confirmed what you tacitly insinuated for this twelvemonth.”5 She confirms that this long-standing estrangement between them had been instigated by the Prince and the Prince alone.

Vindictive libertine

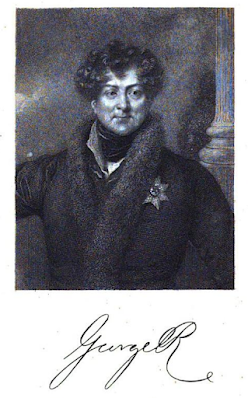

|

George, Prince of Wales

from Memoirs of George IV

by Robert Huish (1830) |

The Prince was inconstant in his affections. In time, Lady Jersey was abandoned for a succession of other mistresses, including a return to his long term lover, Mrs Fitzherbert. But at no time did the Prince show any kindness towards his wife. He did not desire her company, and yet, when he could, he restricted her movements and limited her access to her daughter. She could not expect his love, but she deserved his respect and received none.

In 1806, Caroline’s behaviour was examined by parliament after accusations that she had given birth to an illegitimate child; the “Delicate Investigation” exonerated Caroline, who won great public support through the affair.

When George became king in 1820, he publicly accused his wife of adultery and Queen Caroline was put on trial in an attempt to prevent her from being crowned as queen. Public support once again rallied to the Queen and the Bill of Pains and Penalties, which would have dissolved the marriage, had to be abandoned. George did, however, succeed in barring Caroline from his coronation. Popular media of the time represented George as a libertine and Caroline as the wronged wife.

A disastrous marriage

From start to finish, the Prince’s behaviour was unpardonable. He had agreed to marry Princess Caroline, but failed to show her the respect due to her as wife. He paraded his mistresses in front of her and yet accused her of improper behaviour at every opportunity.

Caroline, on the other hand, was an unfortunate choice of bride; her character and person disgusted her husband and her lack of restraint brought his dislike into the open. Their domestic dispute was paraded in front of the British public for over twenty years, causing the royal family acute embarrassment and loss of popularity.

But perhaps the most sobering reflection is that this match was carried forward against the natural inclinations of both parties and as such, was a recipe for marital disharmony before ever the marriage vows had been exchanged.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) The Act of Settlement of 1701 prevented George from marrying a Catholic, and the Royal Marriage Act of 1772 required the King’s consent to his marriage until he was over 25 years of age. As George III was vehemently opposed to his children marrying beneath them, this effectively left only German royalty as potential spouses.

(2) From a letter dated 28 November 1794 quoted in Opinions on Politics, Theology, &c by Henry Brougham (1839).

(3) From Diaries and Correspondence of James Harris, First Earl of Malmesbury, Volume III (1834).

(4) From John Fairburn's account of the trial of Queen Caroline (1820)(see sources for full title).

(5) From Huish's Memoirs of George IV (1830).

Sources used include:

Brougham, Henry, Baron Brougham and Vaux, Opinions on Politics, Theology, &c (1839)

Cobbett, Cobbett's Political Register (1813)

Fairburn, John, The whole proceedings on the trial of Her Majesty, Caroline Amelia Elizabeth, Queen of England, for 'adulterous intercourse' with Bartolomeo Bergami (1820)

Harris, James, First Earl of Malmesbury, Diaries and Correspondence of James Harris, First Earl of Malmesbury, Volume III (1834)

Huish, Robert, Memoirs of George IV (1830)

Parissien, Steven, George IV, The Grand Entertainment (2001)

Watson, J Steven, Oxford History of England: The Reign of George III 1760-1815 (1960)

wow wow, wow

ReplyDelete