|

| Evening dresses from The Mirror of the Graces (1811) |

Ornamented with Mechlin lace

The first figure in a round robe of white crape, ornamented at the feet with a flounce of Mechlin lace: an horizontal striped front, composed of alternate lace and needlework: short sleeve to correspond: the robe extended over a slip of gossamer satin, either white, blossom-colour, or blue: the hair in curls confined, and ornamented with a bandeau and rose-diadem of pearls, diamonds, or coloured gems; ear-rings, neck-chain and bracelets to correspond: French watch and chain, with a cluster of small variegated emblematic seals: ivory fan, with mount of silver frosted crape: white satin slippers, with silver clasps or rosettes: and white gloves of French kid.1

Mechlin lace originated in Flanders and was traditionally made by hand using a system of bobbins to organise the threads being woven together.

It is a very fine lace with a transparent appearance, particularly known for its floral patterns and outlined designs. It was particularly suitable for trimming garments, such as the evening dress described above. It was sometimes used for gathered trimmings called quillings.

It is a very fine lace with a transparent appearance, particularly known for its floral patterns and outlined designs. It was particularly suitable for trimming garments, such as the evening dress described above. It was sometimes used for gathered trimmings called quillings.

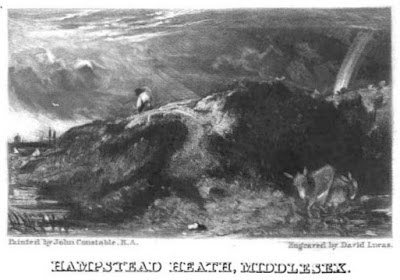

|

| Mechlin lace2 |

The second figure in this plate appears in a robe of green vellum gauze, or Venetian velvet: the bosom and sleeves ornamented with alternate folds of white satin, and finished at the feet en suite: a full long sleeve of white crape: belt of white satin, confined with a large rose clasp of carved mother-of-pearl, with Maltese or convent cross, suspended in front of the bosom: a Grecian scarf of silver tissue, or white French silk, the ends gathered into a globe tassel of silver: the hair in irregular curls and ringlets, twisted on one side the head in the eastern style, and ornamented with rolls of silver frosted crape or gauze, finished on the left side with a silver rose: Grecian sandal-slippers appliqued with silver embroidery in front of the foot: gloves of white kid, and fan of carved ivory.3

Folding fans were popular fashion accessories throughout the Georgian period and were made all over Europe as well as being imported from the Far East by the East India Company.

A folding fan consists of sticks which are joined at the base by a rivet which forms a pivot for the fan to be opened or closed. These sticks are then covered with a pleated leaf which is painted or printed with a design. The outer sticks are called guards and together with the rest of the sticks, they are called montures.

During the Georgian period, the montures were made from materials such as ivory, mother of pearl and tortoiseshell, and were often carved and decorated with precious metals and stones.

The smaller brisé fan was particularly fashionable during the late Georgian and Regency periods. The brisé fan has wider sticks that overlap when open and are joined at the top by a ribbon or thread creating an effect similar to the pleated leaf of the folding fan.

A folding fan consists of sticks which are joined at the base by a rivet which forms a pivot for the fan to be opened or closed. These sticks are then covered with a pleated leaf which is painted or printed with a design. The outer sticks are called guards and together with the rest of the sticks, they are called montures.

During the Georgian period, the montures were made from materials such as ivory, mother of pearl and tortoiseshell, and were often carved and decorated with precious metals and stones.

The smaller brisé fan was particularly fashionable during the late Georgian and Regency periods. The brisé fan has wider sticks that overlap when open and are joined at the top by a ribbon or thread creating an effect similar to the pleated leaf of the folding fan.

|

| Carved ivory fan4 |

Read more about Regency fashion from the The Mirror of the Graces - Regency promenade dresses and Regency morning gowns.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

- A lady of distinction, The Mirror of the Graces; or the English lady's costume (1811).

- Picture of Mechlin lace by Carolus and used under a Creative Commons License.

- A lady of distinction, The Mirror of the Graces; or the English lady's costume (1811).

- Picture of carved ivory fan from the Museum of Liverpool by Reptonix under a Creative Commons license.

Sources used include:

A lady of distinction, The Mirror of the Graces; or the English lady's costume (1811)

A lace lover's diary website

Candice Hern's website - Regency brisé fans

The fan museum website

A lady of distinction, The Mirror of the Graces; or the English lady's costume (1811)

A lace lover's diary website

Candice Hern's website - Regency brisé fans

The fan museum website