It’s well known that the first half of the Regency (1811-1815) saw the end of a long military conflict with France. Wellington’s victory over Napoleon Bonaparte at Waterloo in 1815 concluded a series of wars that began over twenty years earlier, in 1793.

This extended struggle made the military a familiar feature of Regency life. Jane Austen included significant references to both the army and the Royal Navy in her books. Elements of Regency women’s fashion incorporated details from military uniforms.

Today the war with the United States of America, from 1812 to 1814, is little more than a footnote in British history. It’s remembered, even celebrated, in both Canada and the United States. But here in Britain, the War of 1812, as it’s known, is easily overlooked.

The origins of the War of 1812

|

| Morning walking dress with 'military front' from La Belle Assemblée (Mar 1812) |

The American War of Independence had concluded in 1783. By the early 1800s, some of those idealistic young men and women who’d fought for freedom were frustrated by what they considered continued British arrogance.

In particular, the USA objected to Britain interfering with its ships and seamen. The Royal Navy’s domination of the seas meant many American vessels were prevented from trading with mainland Europe. Worse, American sailors were being forced to crew British ships, through the long-established tradition of press gangs.

America wanted to remain outside the conflicts that troubled Europe, and to trade freely with other nations.

Some have labelled the War of 1812 as the ‘Second War of Independence’, in which the young United States asserted its right to be free from British interference.

The USA declares its first war against another nation

Historians argue over the exact causes of the War of 1812. American pride was clearly offended by British treatment of its ships and sailors. It was also offended by Britain inciting Native American tribes to attack American settlers. There’s debate over whether some American politicians hoped a war would lead to the capture of Canada from the British.

Whatever the motivation, the enthusiasm for war grew steadily for several years before 1812.

On 18 June 1812, after several days of deliberation, the American government voted to declare war against Great Britain.

This was the first time the USA formally agreed to go to war with another nation and it wasn’t by an overwhelming majority. Of the 160 politicians who voted, 62 were against going to war.

|

| 200th anniversary ceremony at Fort McHenry, Baltimore, Maryland © Jay Baker, Maryland Govpics 2012 via Flickr |

Principal events of the War of 1812

Despite years of agitation for war, the Americans were not well prepared. Their army comprised ill-equipped local militias who were unwilling to travel far from home. In 1812 and 1813, they launched several small invasions into Canada, all of which were easily repulsed.

The British and American navies engaged in a number of actions off the Atlantic coast of the USA. In order to prevent the Americans from trading, the Royal Navy attempted to blockade the entire eastern coast. In a series of engagements, both sides captured and lost ships. The Americans made considerable use of privateers to bolster their naval forces.

From 1813 to 1815, hundreds of American sailors captured by the British were locked up in Dartmoor Prison.

The Great Lakes, which straddle a huge section of the border between Canada and the USA, saw military action on and off the water. A host of engagements saw first one side gain the upper hand, then the other.

The burning of Washington DC

|

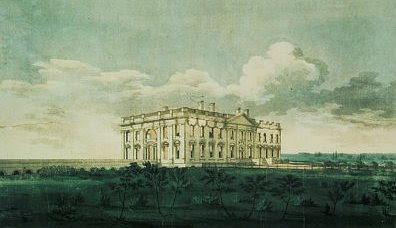

| Burnt out shell of the White House (1814) - engraving by W Strickland after watercolour by George Munger - courtesty of the Library of Congress |

We were all, moreover, from our commanding officer down to the youngest ensign, anxious to gather a few more laurels, even in America.1

In August 1814 a force of 4,500 British troops, supported by ships of the Royal Navy, targeted Washington DC.

The government of the USA had chosen to base itself in Washington DC, moving there in 1800. President James Madison and his government were in the city as the British approached, initially confident that their militia of 6,000 men offered adequate protection.

However, when the militia engaged the British at Bladensburg, six miles from the Capitol, it was clear they were outclassed by the smaller yet more professional army. President Madison himself rode out to witness some of the battle, leaving before the militia fled.

Washington DC was now undefended. According to a later account of a soldier present, the British commander sought payment from the Americans for sparing the city.

It was accepted tradition that the victors could help themselves to the spoils of war. Having limited means to remove valuables, the British knew their only choices were to destroy what they found, or accept a cash payment.

Such being the intention of General Ross, he did not march the troops immediately into the city, but halted them upon a plain in its immediate vicinity, whilst a flag of truce was sent forward with terms. But whatever his proposal might have been, it was not so much as heard; for scarcely had the party bearing the flag entered the street, when it was fired upon from the windows of one of the houses, and the horse of the General himself, who accompanied it, killed. The indignation excited by this act throughout ranks and classes of men in the army, was such as the nature of the case could not fail to occasion. All thought of accommodation was instantly laid aside; the troops advanced forthwith into the town…they proceeded, without a moment’s delay, to burn and destroy every thing in the most distant degree connected with the Government.1

On 24 August 1814, the British deliberately set fire to both the Capitol building and the President’s House, what we now know as the White House.

Our eyewitness noted:

I cannot help admiring the forbearance and humanity of the British troops, who, irritated as they had every right to be, spared as far as possible all private property, neither plundering nor destroying a single house in the place, except that from which the General’s horse had been killed.1

The original star spangled banner

|

| Fort McHenry, Baltimore, from Our Country's Story; an elementary history of the United States by EM Tappan (1908) |

Baltimore’s defences were much stronger than those in Washington DC. After initial forays, the British army decided to hold back until Fort McHenry was neutralised. On 13 September the Navy began bombarding the fort with cannon and Congreve rockets. The attack went on for over 24 hours.

An American lawyer, Francis Key Scott, had boarded one of the Royal Navy ships to negotiate a prisoner exchange. He remained aboard during the bombardment, having no idea of its impact on his fellow countrymen in the fort. On the morning of 14 September, he was delighted to see a large American stars and stripes flag raised over the fort, indicating that its defenders remained resolute. The British finally gave up their attacks on Baltimore and withdrew.

That image of the flag flying in the midst of the bombardment inspired Scott to write a patriotic poem. It was quickly spotted that the poem matched a popular melody and within days it began appearing in American newspapers.

During the later nineteenth century, the song became associated with the raising of the American flag at formal events. In 1931 it was adopted as the National Anthem for the USA.

The original star spangled banner, the flag flown over Fort McHenry in 1814, is in the National Museum of American History, Washington DC.

An account of the bombardment was published in Baltimore a few days after it occurred:

But the attack on Fort M’Henry was terribly grand and magnificent. The enemy’s vessels formed a great halfcircle in front of the works on the 12th, but out of reach of our guns… At 6 o’clock on Tuesday morning, six bomb and some rocket vessels commenced the attack, keeping such a respectful distance as to make the fort rather a target than an opponent; though Major Armistead, the gallant commander, and his brave garrison fired occasionally to let the enemy know the place was not given up! Four or five bombs were frequently in the air at a time, and, making a double explosion, with the noise of the foolish rockets and the firings of our fort, Lazaretto and our barges, created a horrible clatter.2

|

| National star-spangled banner centennial Baltimore, Maryland, September 1914 |

Even as the British and Americans tussled on the battlefields of continental USA in the late summer of 1814, their governments were starting to talk about peace. Negotiations began in Ghent, Belgium.

The Treaty of Ghent was ratified by the British on 27 December 1814 and by the American government on 18 February 1815.

Slow communication meant that even after the treaty was agreed, fighting continued. In late December 1814, a British army began its attempt to capture the city of New Orleans. After some initial successes, the British held back to allow the main body of their army to gather. This gave the Americans, under future President Andrew Jackson, time to construct defences.

The main attack on the city was launched on 8 January 1815 and was a dismal failure for the British. The unit responsible for supplying ladders to the attackers, necessary for climbing the defences, failed to deliver the equipment before the attack was launched.

A British soldier wrote later that soldiers:

...though thrown into some confusion by the enemy’s fire, pushed on with desperate gallantry to the ditch; but to scale the parapet without ladders was a work of no slight difficulty. Some few, indeed, by mounting one upon another’s shoulders, succeeded in entering the works, but these were speedily overpowered, most of them killed and the rest taken; whilst as many as stood without were exposed to a sweeping fire, which cut them down by whole companies.1

Within a few hours, hundreds of British troops were dead, while the American defenders counted only 24 killed, and their defences were unbroken.

The Battle of New Orleans quickly gained a place in American culture as a major symbolic victory.

Who won the War of 1812?

Historians disagree about who, if anyone, won this war between the USA and Britain. The Americans initiated the war partly out of pride and perhaps in the hope of capturing Canada. They failed in the latter but their pride was boosted, particularly by the defence of Baltimore and the victory in New Orleans.

Perhaps some in Britain were pleased with the opportunity for a rematch against the upstarts across the Atlantic, who’d won independence thirty years earlier. They would be disappointed. However, disappointment with events in America were soon to be eclipsed by the re-emergence of a more immediate threat, as Bonaparte returned to France in March 1815.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who wrote this post.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes:

(1) From Gleig, George Robert, The campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, in the years 1814-15 (1821) (This edition 1827)

(2) From The Citizen Soldiers at North Point and Fort McHenry, September 12 & 13 1814 (1889 reprint)

Sources used include:

Gleig, George Robert, The campaigns of the British Army at Washington and New Orleans, in the years 1814-15 (1821) (This edition 1827)

Risjord, Norman K, 1812: Conservatives, War Hawks and the Nation's Honor in The William and Mary Quarterly Vol 18 no.2 (April 1961)

Soldiers' and citizens' album of biographical record containing personal sketches of army men and citizens prominent in loyalty to the union (1890)

The Citizen Soldiers at North Point and Fort McHenry, September 12 & 13 1814 (1889 reprint)