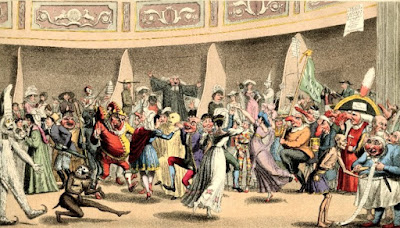

|

| Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, from The Microcosm of London Vol 1 (1808) |

Patty Wilkinson, the daughter of the actor-manager Tate Wilkinson and long-time companion of Mrs Siddons, said that

... before the audience left the house, she perceived a strong smell of fire while she was sitting in Mr. Kemble's box, and spoke of it to several of the servants as she was passing to Mrs. Siddons's dressing-room; but they said that it was only the smell of the lamps in the front of the stage.1

According to the Microcosm of London:

The building was discovered to be on fire, after midnight, on the 19th of September, 1808; and so irresistible were the flames, that before five o’clock on the following morning, nothing remained but an heap of smoking ruins. The real cause of this fatal catastrophe has never been discovered, nor has even a probable conjecture been formed as to the origin of the conflagration.2

The terrible fire was generally attributed ‘to the wadding of a gun, that was discharged in the performance of "Pizarro," having lodged unperceived in some crevice of the scenery.’3

A dreadful loss of life

The Picture of London for 1818 wrote:

But the destruction of the Theatre itself formed but a small part of the calamity: an engine had been introduced within the avenue opening from the Piazza, when, dreadful to relate, the covering of the passage fell in, and involved all beneath in the burning rubbish. The remains of fourteen unfortunate sufferers were afterwards dug out, in a most shocking state; and sixteen others, in whom life remained, were sent to the hospital, most miserably mangled and burnt.4

Another account reported ‘twenty-three firemen being killed by the unexpected fall of a part of the ruins.’5

Campbell’s Life of Mrs Siddons stated:

A number of firemen were crushed under the falling-in of the burning roof, and several unfortunate individuals, having approached the conflagration too nearly, were scalded to death by the steam of the water that arose from it. I shudder in calculating the number of victims —they must have amounted to thirty! Many of them were dug out of the ruins in such a state that they could not be identified.6

Harriot Mellon’s concern

|

| Harriot Mellon as Volante from The Life of Thomas Coutts Banker by EH Coleridge (1920) |

Miss Mellon, who was a great coward respecting fire, was almost out of her senses at the proximity of the flames to her house in Little Russell Street. But when a report arrived that several walls had fallen in and buried a number of poor creatures, her whole anxiety was for their rescue from their dreadful sufferings, if still alive.

Accordingly, with her usual promptitude, she took every measure to aid the great cause of humanity. The compiler of these volumes, on the evening after the fire, when returning home from school under charge of one of her father’s servants, begged hard to be taken to see the ruins. The crowd was alarming; and the servant carried her as near as was practicable, which was to the theatrical book-seller's shop, nearly opposite, which is still kept there.

Many workmen were engaged in digging out the bodies of the unfortunate persons who were buried under the ruins; and they worked by torchlight at their sad occupation. At the door of the bookseller's shop was placed a large barrel of ale, ordered by Miss Mellon, from which the labourers were supplied by her directions. In the drawing-room window above stood Miss Mellon herself, all anxiety, earnestly urging the men to proceed, and offering five pounds for each of those who were brought out alive, and two pounds for each body of the hapless creatures who perished. She was dressed in a blue satin pelisse, looking lovely in her anxiety; and each time she appeared at the window she was received with animated cheers by the crowd, who seemed ready to worship her.

While remaining there, eight individuals were exhumated, and Miss Mellon distributed her rewards; but life was extinct in all, and they were carried to St Paul's churchyard, Covent Garden.7

The unfortunate Mr Webb

One victim of the catastrophe was only discovered three months after the fire. A report in The Gentleman’s Magazine, dated 10 January 1809, said:

The workmen employed in clearing away the ruins of Covent Garden Theatre at the Piazza door, where the Phoenix engine, with the firemen, were so unfortunately destroyed, dug out, near the cistern, the body of a young man, not burnt, but much bruised. It proves to be the son of Mr Webb, of Tottenham-court-road, and had been missing ever since that dreadful morning; but his parents, until the discovery of the corpse, had flattered themselves with the delusive hope that he had been either trepanned into a regiment of the line, or been impressed into the Navy.8

Irreplaceable losses

The loss of property was estimated at £150,000 of which only £50,000 was covered by insurance. Not only the building, but all its contents were destroyed. This included the organ bequeathed to the theatre by Handel and many pages of unpublished manuscript music. All the scenery, costumes, musical and dramatic libraries were lost. In addition, the wines of the famous Beefsteak Club which were stored there were destroyed.

It was a particular blow to the Kemble family. John Kemble, part-owner and manager, was ruined. He had invested everything and more in the theatre and had not repaid what he had borrowed. But Kemble was fortunate in his patrons, who were eager to provide him with the resources to rebuild the theatre. George, Prince of Wales, gave Kemble £1,000 and the Duke of Northumberland gave him £10,000, refusing to make it a loan.

Kemble’s sister, the great tragedienne Sarah Siddons, lost her entire wardrobe – the costumes and jewellery that she had collected over her long career, including the French Queen’s veil which was worth £1,000 alone.

|

| Mrs Siddons from The Portfolio ed PG Hamerton (1894) |

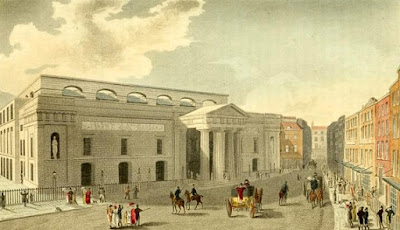

A new theatre rises from the ashes

Extra funds were raised by issuing subscription shares of £500 each and work was soon underway to rebuild the theatre. George, Prince of Wales, laid the foundation stone on 31 December 1808, and within ten months, the new theatre was finished. The new Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, opened on 18 September 1809.

|

| Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, from Ackermann's Repository (1809) |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. From Campbell, Thomas, Life of Mrs Siddons (1834).

2. From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

3. From Campbell, Thomas, Life of Mrs Siddons (1834).

4. Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818).

5. Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 3.

6. From Campbell, Thomas, Life of Mrs Siddons (1834).

7. From Wilson, Mrs Cornwell Baron, Memoirs of Miss Mellon, afterwards Duchess of St Albans new edition Vol 1 (1886).

8. From The Gentleman’s Magazine (1809).

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Campbell, Thomas, Life of Mrs Siddons (1834)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

The Gentleman’s Magazine (1809)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 3

Wilson, Mrs Cornwell Baron, Memoirs of Miss Mellon, afterwards Duchess of St Albans new edition Vol 1 (1886)