|

| Horse guards parading past the Canade Gate, the Green Park |

The Green Park was an area of meadowland enclosed by Charles II after the restoration of the monarchy in 1660. Lying between St James’s Park and Hyde Park, it was formed to link up the royal parks, and was known as Little or Upper St James’s Park until 1746. Charles II built icehouses in the middle of the park.

|

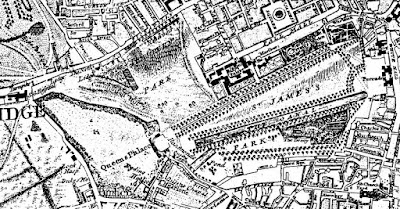

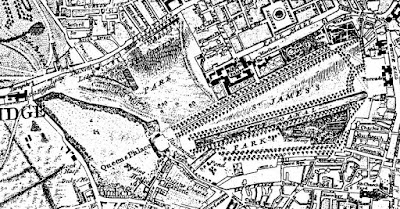

| Rocque's Map of London of 1741-5 showing the Green Park in London in the Eighteenth Century by Sir Walter Besant (1902) |

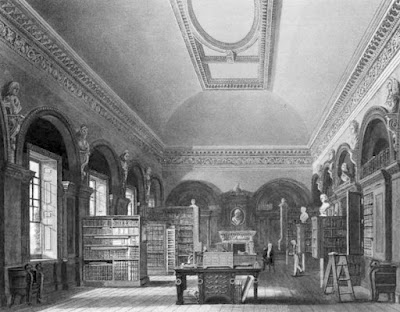

During the 1730s, George II’s wife, Queen Caroline, developed the park. She built a reservoir called the Queen’s Basin which provided water for St James’s Palace, and commissioned a path to the reservoir known as the Queen’s Walk which became a fashionable place to promenade. She also built a pavilion in the park known as the Queen’s Library. It was after a walk to her library that Queen Caroline was taken ill with the complaint from which she never recovered:

On the 9th [November 1737], her majesty [Queen Caroline] having walked to her library in the park, and break fasted there, was taken suddenly ill on her return to the Palace of St. James, with a complaint that was erroneously believed to be the gout in her stomach.1

In 1767, George III reduced the size of the Green Park to enlarge the gardens of Buckingham House.

The peace celebrations of 1749

On 27 April 1749, a huge firework display was held in the Green Park to celebrate the end of the War of the Austrian Succession and the signing of the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle. George II commissioned Handel’s Music for the Royal Fireworks to accompany the display. An enormous pavilion, known as The Temple of Peace, was built in the park for the event and caught fire during the firework display.

|

| View of the peace celebrations in Green Park in 1749 from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

On 1 August 1814, another grand firework display took place in the Green Park, to celebrate 100 years since the Hanoverian Succession and peace with France. Another huge building – The Temple of Concord – was built in the park for the event.

An Historical Memento (1814) recorded:

|

| The Temple of Concord in the Green Park on 1 August 1814 from An Historical Memento by E Orme (1814) |

At ten o'clock, a loud and long continued discharge of artillery announced the commencement of the fireworks; which were, certainly, if not the most tasteful, yet on the grandest and most extensive scale that we have ever witnessed. From the battlements of the castle, at one moment, ascended the most brilliant rockets: presently, the walls disclosed all the rarest and most complicated ornaments of which the art is susceptible: the senses were next astonished and enchanted with a pacific exhibition of those tremendous instruments of destruction invented by Colonel Congreve. Some notion even of their terrible power might be formed from this display, and their exceeding beauty could be contemplated, divested of its usual awful associations. Each rocket contains in itself a world of smaller rockets: as soon as it is discharged from the gun, it bursts and flings aloft into the air innumerable parcels of flame, brilliant as the brightest stars: the whole atmosphere is illuminated by a delicate blue light, which threw an air of enchantment over the trees and lawns, and made even the motley groups of universal London become interesting, as an assembly in romance. These several smaller rockets then burst again, and a shower of fiery light descends to the earth, and extends over many yards. Such was one of the beautiful fireworks, which, during the space of two hours, amused and astonished the people.

But the public, who had been on their legs all day, and were not sufficiently accommodated with seats, began at length to be tired with the endless repetition even of the most striking beauties, and became impatient for the grand metamorphosis of the castle into a temple. This was now the principal object to which the attention of the spectators was awake—the conversion of a fabric, designed for the purposes of war, into a temple of peace, and an illuminated monument of victory. The metamorphosis took place with somewhat less than the celerity generally witnessed in our theatrical pantomines: it resembled the cautious removal of a screen, rather than the sudden leap into a new shape. When fully developed, however, it presented a spectacle, which, for extent of splendour, and not less for tastefulness of arrangement, deserved the admiration, and satisfied the hopes which it had inspired.2

According to some sources, The Temple of Concord met the same fate as the Temple of Peace and was destroyed during a firework display, but Old and New London wrote:

Near Constitution Hill a building was erected from the design of Sir William Congreve (of rocket celebrity), which, with all its palings, and the cordon of sentries round it, covered one-third of the Green Park. This building received the name of the Temple of Concord. The materials of this structure, and of the other erections set up on that occasion, were sold afterwards by auction, and fetched only about £200.3

The Times of 12 October 1814 recorded that The Temple of Concord:

… after having been ineffectually offered for sale by private contract, with all its remaining magnificence, fell yesterday, ingloriously, under the hammer of the auctioneer … It was doubtless the subject of regret to its admirers, that this temple, after shining in all its brilliancy but for one night, should be doomed to such speedy destruction.4

The Green Park in the Regency

|

| The Fountain in the Green Park in 1808 from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

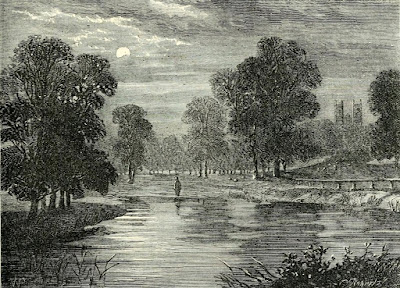

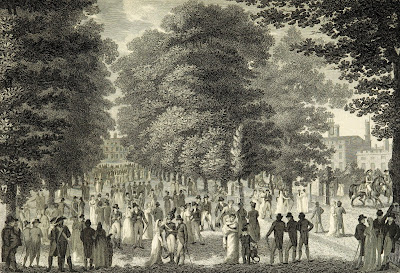

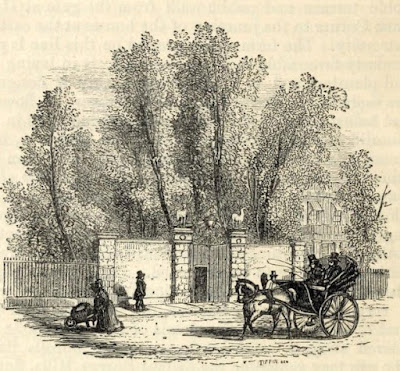

An inclosure, called the Green Park, is a beautiful spot, gradually ascending from St. James's Park, which it immediately joins to Piccadilly, being separated from it by a wall in some parts, and an iron railing in others, and this park is now become the fashionable evening promenade. The lodge of the ranger of Hyde Park stands at the top of this ascent, near the centre, facing Piccadilly and, with its gardens and pleasure-ground, is a very picturesque spot.5

|

| The entrance to the Ranger's Lodge from The story of the London Parks by J Larwood (1874) |

In spring and summer the eastern side of the Green Park forms a favourite promenade for the genteel inhabitants of the metropolis; and in fine weather, on every evening, and on Sundays in particular, it is always crowded with well-dressed company. At the north-east corner of this park there is a fine piece of water, which is supplied by the water-works of Chelsea, and forms at once a beautiful embellishment and a useful reservoir.6

Green Park today

Green Park was opened to the general public in 1826. During the reign of Queen Victoria, the Queen’s Basin was filled in and all the buildings were demolished. Several war memorials have since been erected in Green Park, which is open all day, all year round.

|

| View down Constitution Hill from the top of the Wellington Arch showing the Green Park on the left and Buckingham Palace gardens on the right |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) Pyne, WH, The History of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House and Frogmore (1819).

(2) Orme, Edward (ed), An Historical Memento (1814).

(3) Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878, London) Vol 5

(4) The Times Digital Archive: "Temple of Concord, in the Green Park." Times [London, England] 12 Oct. 1814: 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 5 Sept. 2017.

(5) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813).

(6) Ibid.

Sources used include:

Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Orme, Edward (ed), An Historical Memento representing the different scenes of public rejoicing, which took place the first of August, in St James's and Hyde Parks, London, in celebration of the Glorious Peace of 1814, and of the Centenary of the Accession of the Illustrious House of Brunswick (1814)

Phillips, Richard, Modern London; being the history and present state of the British Metropolis (1804)

Pyne, WH, The history of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House and Frogmore (1819)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878, London) Vol 5

Times Digital Archive

Photos © RegencyHistory