|

|

Two young ladies wearing fashionable afternoon |

One hundred years ago, in the early 1900s, thousands of single young women from wealthy families were sent to finishing schools. The very best were in Switzerland, but wherever the school was, its primary purpose was to turn out refined young ladies fully prepared to be a society wife.

Wind back the clock another hundred years or so to the early 1800s. Were finishing schools doing the same job of polishing a young woman in preparation for marriage?

The short answer is: sort of.

The finishing school, as we’ve come to think of it today, was not quite the same in the late Georgian and Regency era.

We’ve dug out early accounts and descriptions of finishing schools, in order to better understand them.

How a Regency finishing school differs

There are three huge differences between a Regency finishing school and those of the late Victorian era and the first half of the twentieth century.

Firstly, the schools weren’t in Switzerland. Now famous for its neutrality, Switzerland was invaded and captured by the French in 1798. This led to years of political instability until 1815.

Secondly, the young women who attended finishing schools were not drawn from the cream of society. Private tutoring, overseen by a governess, was the preferred method of educating girls and young ladies. This was expensive, making it exclusive to the wealthy. Finishing school was a second-best option.

Thirdly, the quality of education was patchy. Many thought that the students learned little, if anything, in such establishments.

Charles Dickens captures this sentiment in Sketches by Boz, in an episode first published in a magazine in 1834. He describes a fictional school:

Minerva House, conducted under the auspices of the two sisters, was a ‘finishing establishment for young ladies,’ where some twenty girls of the ages of from thirteen to nineteen inclusive, acquired a smattering of everything, and a knowledge of nothing; instruction in French and Italian, dancing lessons twice a-week; and other necessaries of life.1

In his story, a Member of Parliament puts his daughter in the school to hide her from a potential suitor. It’s not long before she elopes, and the MP exclaims:

“I’ll bring in a bill for the abolition of finishing-schools.”2

While Dickens’ story is fiction, and he liked to poke fun at many aspects of society, his poor opinion of finishing schools is shared by others—as we’ll see below.

There’s one final difference to note—the term ‘finishing school’ was not restricted to places where girls were educated.

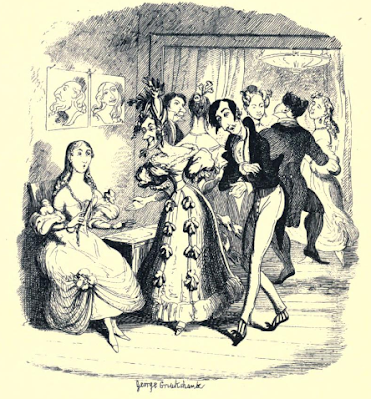

|

| Theodosius is introduced to the new pupil by George Cruikshank in Sketches by Boz by Charles Dickens (1836) |

Regency finishing school wasn’t just for women

Words and phrases often change their meaning over time, and this is what’s happened to ‘finishing school’.

In its more general sense, a finishing school was a place where someone’s education was rounded off, or finished. This could apply as much to a man as a woman.

In a book on university education for doctors published in 1759, Richard Davies wrote:

After giving some public proof of a natural Genius, Students should be sent for instruction to the national Schools; there to pass thro’ all the discipline of a philosophic Education; to be afterwards improved by due attendance as some public Hospital. Which ought to be the finishing school of the clinical Physician.3

This usage appears in other documents around that time. A ‘finishing school’ wasn’t so much a specific institution as an environment where your education was completed. On leaving, students were equipped for a particular station in life.

In The Art of Teaching by David Morrice, 1801, that author writes:

What are called FINISHING SCHOOLS in London, are of very great service to young gentlemen designed for the commercial line, as they are there more particularly instructed with a view to that object, and by masters practically versed in the business.

Half a year’s instruction at one of these academies, after leaving a country school, will greatly benefit a youth, and prepare him for the counting-house with much advantage.4

For late Georgian women, that final stage of education included the knowledge of running a household. Indeed, preparing them to be a good wife was the primary purpose of their education.

This emphasis is captured in A Picture of Manchester (1826), which states that in the same way that young men finish their studies at university:

...so the young ladies in those days completed theirs under the celebrated Mrs Blomiley, without which (provided the deficiency in education was known) it would have been vain for them to hope that any young man would deem them fit to be his wife.5

A Regency finishing school was not a premium education

Those who could afford it usually educated their daughters at home. They sent their sons to boarding schools, such as Harrow and Eton, where they were harshly treated, but could get up to all kinds of mischief. Girls needed more protection—and less education.

There were boarding schools for girls, and plenty of them, often run in private homes, with relatively small numbers of pupils.

The students were usually drawn from middle-class families who wanted their daughters to improve themselves—or be ‘finished’.

In her finishing school, the celebrated Mrs Blomily of Manchester educated the daughters of merchants—very much the middle classes.

|

| Lady Morgan (born Sydney Owenson) from The Missionary by Lady Morgan (1811) |

…placed us in the fashionable “finishing school,” as it was then called, of Mrs Anderson.

The pupils were the daughters of wealthy mediocrities, and their manners seemed coarse and familiar after the polished formalities of the habits of St Cyr.6

In a letter to her father, preserved in the memoir, Sydney expressed her dislike of the ‘vulgar’ and ‘odious’ Mrs Anderson, and complained she learned nothing new in her time there.

Sydney Owenson later became Lady Morgan, a noted Irish author.

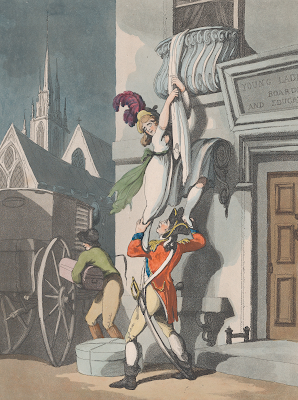

Another author, Thomas Hamilton, is equally uncomplimentary about a ‘finishing school’ education and its impact on a woman’s morals. In his novel The Youth and Manhood of Cyril Thornton (1827), he uses his characters to describe the girls who attend such schools as “always pert, forward, ill-educated and ill-bred.”7

Hamilton also has his character tell the story of a girl, “only lately returned from a finishing-school at Bath”, who marries an officer and soon elopes with another.8

The attitude towards finishing schools was not particularly positive.

|

| Smuggling Out or Starting for Gretna Green by Thomas Rowlandson (1798) |

Young ladies of quality did not attend a Regency finishing school

Our research suggests that the late Georgian and Regency idea of a finishing school was quite different from that we now associate with the phrase.

It was a term applied to any institution where any person’s education was considered to have been ‘finished’. That is, on leaving, they were ready for the duties for which the school had equipped them.

For women, that duty was to be a good wife. The wealthy employed governesses and tutors to achieve this finishing. The middle classes sent their daughters to a school where they hoped it would take place.

Many people had a low opinion of schools that promised to deliver this ‘finish’ for women.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

- Dickens, Charles, Sketches by Boz (1836).

- Ibid.

- Davies, Richard, MD, The general state of education in the universities (1759).

- Morrice, David, The Art of Teaching (1801).

- Aston, Joseph, A Picture of Manchester (1826).

- Morgan, Lady, Lady Morgan’s Memoirs Volume 1 (1862).

- Hamilton, Thomas, The Youth and Manhood of Cyril Thornton (1827).

- Ibid.

Sources used include:

Aston, Joseph, A Picture of Manchester (1826)

Davies, Richard, MD, The general state of education in the universities (1759)

Dickens, Charles, Sketches by Boz (1836)

Hamilton, Thomas, The Youth and Manhood of Cyril Thornton (1827)

Morgan, Lady, Lady Morgan’s Memoirs Volume 1 (1862)

Morrice, David, The Art of Teaching (1801)

© RegencyHistory

On Sydney Owenson, whose most famous book, perhaps, is A Wild Irish Girl. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sydney,_Lady_Morgan

ReplyDeleteIt should be noted, however, that most of the subjects were subjects that people are campaigning to put back in school today: household management (aka Home Ec), herbalism/First Aid, music, the arts, modern languages (and a child who knows both French and German can easily learn Latin; Greek, however, has the complexity of German and the irregularity of English and thus would prove more difficult)...

ReplyDeleteThe only reason a masculine education was valued over a feminine education was sexism! Women learned actual marketable skills (all those "ornamental" qualities) as well as Adulting, whereas men learned Roman literature, cricket, how to survive severe malnourishment, and how to good head (granted, the last of which _was_ a marketable skill).

While I agree with you on many points, I have to point out that not all finishing schools were made equal, some of them provided a more rounded, extensive education that could be easily obtained at home from a governess. After all, where did a governess learn her skills? Frequently, at a similar school. At least, at a London school better teachers could be found. For example, Frances Lady Shelley noted in her diary that she owed the most valuable part of her education entirely to the 2 years she spent, aged 15 to 17, to the school of Mrs. Olier, aunt of the celebrated Sydney Smith (one of founders of the Edinburgh Review). Another famous ladies' school I know of was at 22 Hans Place, where quite a few well-known 19-century female authors were educated, including Mary Russell Mitford, Letitia E. Landon, Rosina Bulwer Lytton and others. The school was a successor to the Reading Abbey school where Jane Austen went. There were undoubtedly other superior schools, especially in London and Bath. That being said, I supposed the quality of education greatly depended on the headmistress or owner of the establishment. Most schools, I imagine, were very much like the one like the one that Mrs. Goddard ran in Highbury.

ReplyDeleteI also have to disagree with your statement that upper class girls wouldn't attend school. Lady Caroline Lamb attended 22 Hans Place. Mrs. Olier's pupils were daughters of aristocrats or rich gentry. Elizabeth Knight and her sisters, daughters of a baronet, attended a female seminary.

Ambassadors, colonial statesmen and landowners, high-ranked army and navy officers could and did send their daughters to schools, because their lifestyles prevented employment of good tutors, and governesses' education was frequently inferior. I recommend reading 'Memoirs of a Highland Lady' by Elizabeth Grant for the description of her schooling and early years. Memoirs of Susan Sibbald are also interesting in this respect.

As of the contemporary criticism of girls' schools, I wonder how much of it was due to the perennial resistance of men to allowing girls learn anything above and beyond needlework and rudiments of reading and writing. The general attitude, too, was that everything other than Classics was an 'accomplishment' and therefore frivolous, somewhat immoral and unnecessary.