|

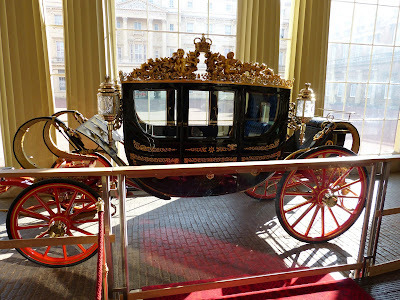

| Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

‘A beautiful object’

The Gold State Coach is on display in the former State Carriage House at the Royal Mews. It measures 7.3 metres long, 2.5 metres high and 3.9 metres wide, and is gilded all over.

|

| Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

|

| Lion detail on Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

The exterior boasts exquisitely painted panels by the Florentine artist, Giovanni Battista Cipriani.

|

| Panel detail on Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

On its roof, there are three cherubs representing the guardian spirits of England, Scotland and Ireland, supporting the Royal Crown, and holding the Sceptre, the Sword of State and the Ensign of the Knighthood in their hands.

|

| Cherubs on the roof of the Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

The body of the coach is supported by braces covered in Morocco leather decorated with gilded buckles held by Tritons.

|

| Triton detail on Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

Horace Walpole wrote to his friend Horace Mann:

There is come forth a new state coach, which has cost 8,000l. It is a beautiful object, though crowded with improprieties. Its support are Tritons, not very well adapted to land-carriage; and formed of palm-trees, which are as little aquatic as Tritons are terrestrial. The crowd to see it on the opening of the Parliament was greater than at the coronation, and much more mischief done.1

George III commissioned the Gold State Coach in 1760 and it was designed by the architect Sir William Chambers. As Walpole wrote in his letter, the coach cost nearly £8,000 to build. Based on the Retail Price Index, £8,000 would equate to well over £1,000,000 in today’s money. If we consider relative incomes, the equivalent cost would be as much as £14,000,000 or more.2 This seems uncharacteristically extravagant of George III.

Given the cost of building the Gold State Coach, it is perhaps surprising to discover that it was made not for George IV – renowned for his profligacy and love of pomp and ceremony – but for his much more frugal father.

The Gold State Coach’s first outing

The coach was completed in time for the State Opening of Parliament on 25 November 1762. Its first journey was deemed a success, despite the fact that one of the door handles broke and a pane of glass cracked.

Driving the coach

|

| Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

Originally, the coach was pulled by eight Cream Hanoverian stallions, with six of the horses being driven by a coachman from the box and the leading pair being driven by a postilion riding one of them. From 1918 to 1925, black horses were used, but since George VI’s coronation in 1937, the coach has been drawn by Windsor Greys.

The hammer cloth and box were removed by Edward VII to promote greater visibility and the coach is now pulled by eight postilion-driven horses.

Because of its weight, the coach can only travel at a walking pace and is no good at all on hills. It also takes a very long time to stop. A brakeman walks immediately behind the coach, ready to operate the brake handle when required. The brake needs to be applied approximately 27 metres before the desired stopping point.

Unfortunately, the magnificence of its exterior is not matched with the comfort of the ride. The body of the coach is supported by leather braces and not only rocks backwards and forwards, but sways from side to side as well.

|

| Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

Coronations and jubilees

The Gold State Coach has been used at every coronation since that of George IV in 1821. The frieze around the walls of the former State Carriage Room where the coach is on display was painted by Richard Barrett Davis (1782-1854) and depicts the coronation procession of William IV in 1831.

The coach is still used today, but only for special occasions. This is just as well as a large section of the wall on one side of the carriage room has to be removed in order to get the enormous coach out.

The Queen used the Gold State Coach for her coronation on 2 June 1953. It was last used on 4 June 2002 as part of the Queen’s Golden Jubilee celebrations.

|

| Gold State Coach at the Royal Mews, Buckingham Palace |

Last visited 1 August 2017 for Bloggers' breakfast event.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) In a letter dated 30 November 1762, from Walpole, Horace, Letters of Horace Walpole to Sir Horace Mann volume 1 p126 (1833).

(2) Relative values calculated using the Measuring Worth website (see link below).

(2) Relative values calculated using the Measuring Worth website (see link below).

Sources used include:

Vickers, Hugo, The Royal Mews at Buckingham Palace (Royal Collection Enterprises Ltd, 2011)

Walpole, Horace, Letters of Horace Walpole to Sir Horace Mann volume 1 (1833).