|

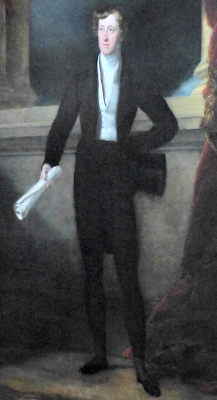

| A duke from A book explaining the ranks and dignitaries of British Society by C Lamb (1809) |

There are five ranks of the British peerage: duke, marquess, earl, viscount and baron.

These are all hereditary titles and, with a few exceptions, pass down from father to son in the male line.1

How do you inherit a dukedom?

To inherit a dukedom, you would need:

- To be a direct male descendant of a previous holder of the title.

- For all those with a greater claim to the title (if any) to have already died.

Normally, the dukedom would descend to the duke’s eldest son. But if he has already died, the dukedom would pass to the eldest son’s eldest son.

But what if both son and grandson have died or the duke has no sons?

The order of succession

You continue down the order of succession until you find a direct male descendant who is alive. The order of succession would look something like this:

- Duke’s eldest son and his direct male descendants, eldest first

- Duke’s 2nd son and his direct male descendants, eldest first

- Duke’s 3rd son etc If the Duke’s father held the title before him

- Duke’s next eldest brother and his direct male descendants, eldest first

- Duke’s next eldest brother etc If the duke’s grandfather held the title before him

- Duke’s father’s next eldest brother and his direct male descendants, eldest first

If there are no direct male descendants of a previous holder of the title, then the dukedom would normally become extinct.2

If, say, the current duke had been granted the dukedom and his father was only an earl, then his brothers could only inherit the earldom, not the dukedom, as they are not direct male descendants of a previous holder of the title.

|

| Francis Russell, 5th Duke of Bedford (1765-1802) Died unmarried and was succeeded by his brother, John from The Life of George Brummell by W Jesse (1886 edition) |

If the heir is the son of the current duke, then he usually takes the next highest title of the duke as a courtesy title before he inherits. The eldest son is known as the heir apparent as he is the highest in the succession order above, and will definitely inherit if he is still alive at the time of his father’s death.

In the same way, if the eldest son has died, his eldest son would be heir apparent and take his father’s courtesy title.

You can read more about the use of titles here.

If there is the possibility that another male could be born who would push the heir down the succession order, he is known as the heir presumptive.

Only direct descendants of the current duke can take a courtesy title.

What title, if any, do the relatives of the new duke use?

If the heir is a direct descendant of the current duke, then his mother and siblings will already have titles as the wife and children of the duke.

But if the heir is lower down the line of succession, then his mother and siblings may not have any title at all.

Typically, the siblings of the new duke will be awarded the rank and title of children of a duke by a royal warrant of precedence.

However, this does not usually apply to the duke’s mother who retains her previous rank.

The Dukes of Devonshire

I think it’s easier to explain using a real-life example, so we’ll look at the Dukes of Devonshire. The only problem with this example is that there are a lot of Williams!

|

| William Cavendish, 4th Duke of Devonshire, after Thomas Hudson Hardwick Hall © National Trust via WikiMedi Commons |

William (1748–1811)(William 5)

Lord Richard (1752–1781)

Lord George (1754–1834) – made 1st Earl of Burlington in 1831.

On the death of William 4 in 1764, he was succeeded by his eldest son William 5 who became the 5th Duke of Devonshire. William 5 only had one son:

(Yet another) William (1790–1858), (William 6) who became the 6th Duke on his father’s death.

|

| William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire - on Oak Stairs at Chatsworth Photo © A Knowles (2014) |

When William 6 died, the title would have passed to his next oldest brother, but as he didn’t have any brothers, we have to go back another generation to the next oldest son of William 4.

However, Lord Richard had already died unmarried in 1781, so we have to go to William 4’s third son, Lord George. By the time William 6 died in 1858, George had already died, but George had married and had sons. The eldest of these was another William Cavendish (1783–1812).

As you can see from his dates, he had already died as well. But he had married, and his eldest son was also William Cavendish (1808–1891) (William 7) who became the 7th Duke of Devonshire.

William 7 already had a title – he had become the 2nd Earl of Burlington on his grandfather’s death in 1834.

If a person has already died, they cannot inherit a title posthumously. So, William 7’s father was never an earl or a duke and is always referred to as William Cavendish.

However, when a man inherits a title that his father would have inherited had he still been alive, his siblings may be granted the precedence as if he had inherited, by Royal Warrant. As Black points out, though, this is not a right but by favour of the Crown.3

So, when William 7 became Earl of Burlington in 1834, his brothers were granted the precedence of younger sons of an earl, and his sister, the precedence of a daughter of an earl.

In the same way, when William 7 became Duke of Devonshire in 1858, his brothers were granted the precedence of younger sons of a duke, and his sister, the precedence of a daughter of a duke.

His mother, however, who was still alive at the time, did not inherit the title of dowager countess or dowager duchess.4

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

- Some ladies hold a title in their own right. These titles, mostly baronies and a few earldoms, descend in the female line.

- Sometimes, a peer was given royal permission for his title to be inherited differently, eg an Act of Parliament gave John Churchill, 1st Duke of Marlborough (1650–1722), the right for his title to descend to his daughter Henrietta and then to his second daughter’s son.

- Black, Adam and Charles, Titles and forms of address - a guide to their correct use (9th edition)(1955).

- There is a long list of Royal Warrants of Precedence on Wikipedia, and this list doesn’t include any 19th century cases of precedence being granted to widows of peers. You can find the list here. The entries are all referenced with announcements in the Gazette.

Black, Adam and Charles, Titles and forms of address - a guide to their correct use (9th edition)(1955)

Courthope, William, editor, Debrett's Complete Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1838)

Lamb, Charles, A book explaining the ranks and dignities of British Society (1809)