|

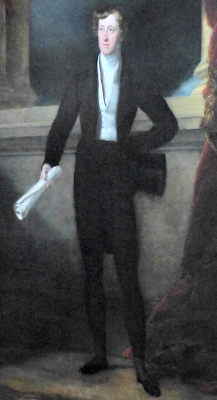

| William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire - on Oak Stairs at Chatsworth Photo © A Knowles (2014) |

William Spencer Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire (21 May 1790 - 18 January 1858), was known as the Bachelor Duke, because he never married. He was a patron of the Whigs, but his absorbing passions were more cultural than political with deep interests in horticulture, literature, science and sculpture.

Birth and family

William Spencer Cavendish was born in Paris on 21 May 1790, the long-awaited son and heir of William Cavendish, 5th Duke of Devonshire, and his first wife, Lady Georgiana Spencer. He had two older sisters, Georgiana (1783-1858) and Harriet (1785-1862). His family called him Hart (as I have throughout this post), an abbreviation of his title, the Marquess of Hartington, which he used from birth until he became Duke. Hart was baptised at St George’s Hanover Square on 21 May 1791.

|

| Bust of William Cavendish, 6th Duke of Devonshire in Sculpture Gallery, Chatsworth © A Knowles (2014) |

The relationship between Hart’s parents was very strained. They lived in a strange ménage à trois with Georgiana’s intimate friend, Lady Elizabeth Foster, who was also the Duke’s mistress. Indeed, rumours circulated from time to time that Lady Elizabeth was really Hart’s mother.

Georgiana’s huge gambling debts threatened her marriage, but it was her affair with Charles Grey, later 2nd Earl Grey, which brought things to a head. Georgiana became pregnant with Grey’s child and the Duke sent her abroad in disgrace. She gave birth to her daughter Eliza in February 1792, but she was not allowed to return home until the following autumn.

For two years, Hart and his sisters were left under the care of their governess, Selina Trimmer. When Georgiana returned, the three-and-a-half-year-old Hart did not recognise his mother and screamed when she tried to touch him. It later transpired that he was profoundly deaf – the result of an infection he had contracted whilst she was abroad. Georgiana felt so guilty for being away that she was inclined to spoil her son.

|

| Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire, and child after the painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds from The Two Duchesses (1898) |

Education and character

As a boy, Hart was temperamental and isolated, and his mother deplored the fact that he seemed to prefer the company of servants. He was educated at Harrow School before going up to Trinity College, Cambridge. He continued to shy away from physical contact and was inclined to hysterics if his sisters teased him.

Lady Caro

Hart was very attached to his cousin, Lady Caroline Ponsonby, and was distraught when she married William Lamb, the future Prime Minister, Lord Melbourne, in 1805. It was, however, the act of allowing his mother to comfort him that established a friendship between them that had been lacking.

|

| Lady Caroline Lamb from Wives of the Prime Ministers (1844-1906) |

Lady Elizabeth Foster

After Georgiana’s death in March 1806, Hart and his sisters deeply resented Lady Elizabeth Foster taking their mother’s place and her eventual marriage with their father in October 1809. In later years, however, the new Duchess seemed to regain the influence which she had possessed over Hart as a child.

|

| Lady Elizabeth Foster, later Duchess of Devonshire, in South Sketch Gallery, Chatsworth |

The 6th Duke

Hart became the 6th Duke of Devonshire on the death of his father on 29 July 1811, at the age of 21. He inherited eight houses, including Chatsworth, Devonshire House, Hardwick Hall and Chiswick, and around 200,000 acres of land. He took his family responsibilities very seriously and continued to pay off his mother’s debts.

Politics

|

| The Oak Stairs, Chatsworth © A Knowles (2014) |

Hart was a Whig and a reformist, but more through patronage than from an active political career in the House of Lords as he was impeded by his deafness.

He was appointed Ambassador Extraordinary to the Russian Empire and visited St Petersburg in 1826 for the coronation of Tsar Nicholas I and was decorated with the orders of St Andrew and St Alexander Nevsky in recognition of the £26,000 of his own money he spent on the occasion.

Hart was sworn in as a member of the Privy Council in April 1827 and was Lord Chamberlain to George IV (1827-8) and William IV (1830-4). He took over from his father as Lord Lieutenant of Derbyshire in 1811, a position he held until his death.

Hart was a friend of the Prince Regent, later George IV, and carried the orb at his coronation in 1821.

|

| George IV in his coronation robes from An authentic history of the coronation of His Majesty, King George the Fourth by Robert Huish (1821) |

The Bachelor Duke

After his disappointment over Lady Caro Ponsonby, Hart did not embark upon any serious courtship – at least not one that is mentioned in any of my chief sources. He did, however, appear to have had at least one mistress. He had a secret, ten-year relationship with Eliza Warwick from 1827, but little is known about her. It has been suggested that Hart abandoned Eliza after his conversion to Evangelical Christianity.

Modernisation of Chatsworth

Hart employed the architect Sir Jeffry Wyatville to modernise and extend Chatsworth. He built a magnificent oak staircase leading to the new north wing which included a Dining Room, Orangery, private Theatre and Sculpture Gallery. He also turned the Long Gallery into the Library and added ground floor windows to the Painted Gallery.

Redecorating Chiswick

|

| The Library, Chatsworth © A Knowles (2014) |

In the 1840s, Hart lavishly redecorated the interiors of Chiswick House, using the firm of Crace & Son. His sister Harriet exclaimed:

Oh! Chiswick! Dearest brother, Chiswick! What shall I say? Chatsworth, be jealous.1

Sadly, the decorations were left to decay and the east and west wings were demolished in the 1950s. You can read a description of the decorations on the Chiswick House website.

Horticulturalist

Hart made Joseph Paxton Head Gardener at Chatsworth and with his help, he redeveloped the gardens. Hart was very fond of travelling and in 1838, Paxton accompanied him on a Grand Tour of Europe. He built the Rockery at Chatsworth to imitate the alpine scenery. He also built the Emperor Fountain, which can rise to the height of 90 metres, and the Grand Conservatory – the forerunner of Paxton’s Crystal Palace, built for the Great Exhibition of 1851.

Hart was President of the Royal Horticultural Society (1838-58) and the Cavendish banana is named for him.

Hart the collector

|

| The Emperor Fountain, Chatsworth © A Knowles (2014) |

|

| The Sculpture Gallery, Chatsworth © A Knowles (2014) |

He was passionate about marble and formed a great friendship with the sculptor Antonio Canova. The Sculpture Gallery was created to display his collection of contemporary sculpture and is presided over by busts of Canova and Hart.

|

| Bust of Canova in Sculpture Gallery, Chatsworth © A Knowles (2014) |

Hart the historian

Hart was also very interested in the history of his family and of their estates at Chatsworth and Hardwick. In 1844, he privately published the first volume of a book called Handbook to Chatsworth and Hardwick, written in the first person to his sister, Harriet, Countess Granville.

He was instrumental in the formation of the Derby Museum and Art Gallery in 1836.

Debts

Hart’s expensive habits of building, collecting and travelling came with a cost. He ran up extensive debts and was obliged to sell some of his estates to settle them.

Illness and death

Hart suffered a paralytic seizure in 1854 and died at Hardwick Hall in Derbyshire on 18 January 1858. He was buried at Edensor, Derbyshire.

He was succeeded by his first cousin, once removed, another William Cavendish, 2nd Earl of Burlington (1808-1891).2

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. From the Chiswick House website (see link below).

2. The 7th Duke's father, yet another William Cavendish (1783-1812), was Hart's first cousin, and he would have inherited if he had not already died.

2. The 7th Duke's father, yet another William Cavendish (1783-1812), was Hart's first cousin, and he would have inherited if he had not already died.

Sources used include:

Cavendish, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire and others, The Two Duchesses, Family Correspondence, ed by Vere Foster (Blackie & Son, 1898, London)

Foreman, Amanda, Georgiana, Duchess of Devonshire (HarperCollins, 1998, London)

Fowler, Claire, Your guide to Chatsworth (Chatsworth House Trust, 2010)

Huish, Robert, An authentic history of the coronation of His Majesty, King George the Fourth (1821)

Reynolds, KD, Cavendish, William George Spencer, 6th Duke of Devonshire (1790-1858), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 30 Oct 2014)