|

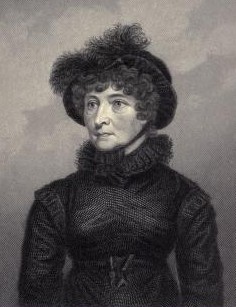

| Fanny Burney from Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay (1846) |

Fanny Burney (13 June 1752 - 6 January 1840) was an English novelist and diarist who served as second keeper of the robes to Queen Charlotte from 1786 to 1791. Her works include Evelina and Cecilia and her journal which was published after her death.

Early life

Frances Burney was born in King’s Lynn, Norfolk, on 13 June 1752, the third child of Charles Burney, a talented musician and author, and his wife Esther.

Frances, known as Fanny, was plain and short-sighted and struggled to learn to read. She was also extremely shy and had a serious manner about her, far beyond her years, which gained her the nickname “the Old Lady”.

Despite this, by the age of ten, Fanny had acquired a life-long love of writing and at the age of fourteen, she started to write a journal in the form of letters to her sister Susan and a family friend, Samuel “Daddy” Crisp.

Exalted company

In 1760, the family moved to Soho, London, where her father became a music teacher. Two years later, Fanny’s mother died of consumption, and in 1767, her father married again. Fanny’s stepmother, Elizabeth Allen, was a widow and long-time friend of the Burneys, but Fanny struggled to get on with her.

Fanny acted as secretary for her father who was working on a history of music. Charles Burney’s circle of friends included the lexicographer Samuel Johnson, the poet Christopher Smart, the painter Joshua Reynolds, the actor David Garrick and a brewer Henry Thrale and his wife, Hester, a diarist.

|

| Hester Piozzi, formerly Thrale from Autobiography Letters and Literary Remains of Mrs Piozzi (Thrale) (1861) |

On 29 January 1778, Fanny’s first novel, Evelina, or A Young Lady’s Entrance into the World, was published. The book was written in letter form and published anonymously and secretly with the help of her brother; not even her father knew she had written it.

Evelina was favourably received and when Fanny’s authorship became known, her father’s friend Hester Thrale demanded an introduction. Her celebrity as an author gained her entrée to literary circles and she became friends with the bluestocking hostess Elizabeth Montagu and through her, to the writer and artist Mary Delany.

|

| Madame Duval is furious from Evelina by Fanny Burney (1808 edition) |

On the advice of her father and Daddy Crisp, Fanny abandoned a play, The Witlings, a satire on the literary world, which she was writing, on the grounds that it might offend. Instead she concentrated on her second novel, Cecilia, or Memoirs of an Heiress, which was published on 12 June 1782.

|

| Cecilia and Mr Briggs from Cecilia by Fanny Burney (1825 edition) |

Through Mrs Delany’s influence, Fanny was presented to the King and Queen, and this was followed by the invitation to become second keeper of the robes for Queen Charlotte. Fanny was loath to accept. She feared separation from her friends and the heavy demands of the role, but her father’s enthusiasm for her to accept this mark of Royal favour, coupled with increasingly strained relations with her step-mother, eventually persuaded her to consent.

On 17 July 1786, Fanny began five years of service to the Queen. Her journals stand witness to the monotony of her days and the difficulties of dealing with her superior, Madame Elizabeth Schwellenberg. Her stress multiplied with the onset of the King’s illness in 1788, though the tedium was alleviated by a visit to Weymouth the following summer. But the rigours of the role were taking their toll on Fanny’s health and she petitioned the Queen to be allowed to retire. She was eventually released on 7 July 1791 on half pay.

|

| Queen Charlotte from Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay (1846) |

Still single at forty, Fanny must have doubted her chances of ever marrying. She had rejected the suit of a stiff young man named Thomas Barlow in 1775 and her court dalliance with Colonel Stephen Digby, Queen Charlotte’s vice chamberlain, had come to nothing.

But in 1793, Fanny met Alexandre d’Arblay, one of a party of French aristocrats who had fled to England to escape the revolution. The group of émigrés also included Madame de Stael and Charles Talleyrand.

Fanny fell in love with Alexandre and persuaded her family to accept their marriage, despite his Catholicism and penniless state. They were married on 28 July 1793 and a son, Alexander, was born the following year on 18 December 1794.

Camilla

Fanny wrote a new novel, Camilla, or A Picture of Youth, which was published on 12 July 1796. Although it was received less warmly than her previous books, it was her biggest financial success. She sold the copyright for £1,000 and received at least as much again from a subscription. The list of subscribers included Elizabeth Montagu, Hannah More, Ann Radcliffe and Jane Austen.

Paris

In 1801, Alexandre returned to France to try and reclaim his property and the following year, after peace had been declared, Fanny went to join him. They spent the next ten years living in the Paris area. In September 1811, Fanny underwent a mastectomy operation, performed by Dominique Jean Larrey, Napoleon’s surgeon, without anaesthetic.1

The Wanderer

In 1812, Fanny returned to England with her son, and in 1814, she published her last novel, The Wanderer, or Female Difficulties. The book was not very popular but she received £1,500 for the first edition.

Waterloo

Fanny returned to France in November 1814 when her husband resumed his military service and witnessed the run up to Waterloo which she recorded in her journal. Alexandre was injured, forcing him to retire from the army, and the family returned to England to live in Bath in October 1815.

|

| Bath Abbey |

In October 1817, Fanny had a harrowing experience at Ilfracombe in Devon when she was cut off by the tide and nearly drowned.

Then, on 3 May 1818, Alexandre died. Fanny was grief-stricken. In the years that followed, she devoted herself to compiling her father’s memoirs which were published in 1832. Fanny’s unsatisfactory and undistinguished son died of a fever on 19 January 1837.

Fanny died in London on 6 January 1840. Her journals, which she had carefully edited to exclude unpleasant family matters that she did not want generally known, were published posthumously and give a wonderful insight into Fanny’s life and the world she lived in.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Note

(1) Referred to as Dominique-Jean Larron in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography entry on Fanny Burney by Pat Rogers (2004).

Read about how Fanny Burney's writing influenced Jane Austen.

Sources used include:

Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett (Henry Colburn, 1846, London)

Chedzoy, Alan, Seaside Sovereign - King George III at Weymouth (The Dovecote Press, 2003, Wimborne)

Hodge, Jane Aiken, Passion and Principle (John Murray,1996,London)

Rogers, Pat, Burney, Frances (1752-1840) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn, May 2010, accessed 7 June 2012)

Thrale, Hester, Autobiography Letters and Literary Remains of Mrs Piozzi (Thrale) edited by A Hayward (Longman, Green, Longman & Roberts, 1861, London)

All photographs © Andrew Knowles & RegencyHistory.net

I love the novel Evalina. We read it at university, I've re-read it for pleasure since and I would read it again tomorrow. It's time they made that into a costume drama!

ReplyDeleteI must try that one - thanks for the recommendation :)

Delete90 per cent of Jane Austen's letters were destroyed by her sister Cassandra and all of Eliza's letters were destroyed by the Austen family. The only possible reason for this was to disguise the true author. The reason that Jane Austen discussed novels while they were being written was that she was staying at the time at Eliza's home in London where she acted as her secretary and proofreader. I think that the writing style of both authors is similar, as it is based on a latinate style and especially on the Latin author Tacitus. The last of Fanny Burney's novels, Camilla, is written in a very similar style to early Jane Austen novels.

DeleteI haven't read Camilla yet. I will have to read it and see whether I think the styles compare.

DeleteThis is a very good "official" biography of Fanny Burney but sadly is not true. As I show in my recently published book "Jane Austen - a New Revelation" the first three novels of Fanny Burney (Evelina, Cecilia and Camilla) were in fact written by Jane Austen's cousin Eliza de Feullide, who later went on to write the novels now attributed to Jane Austen. The highly educated Eliza could not publish under her own name as she was the secret illegitimate daughter of Warren Hastings, the Governor General of India.

ReplyDeleteThe only novel Fanny Burney actually wrote herself was The Wanderer, as Fanny Burney did not have access to the writing skills of Eliza de Feuillide at this time, since she was stuck in France from 1802 to 1812 when she wrote it. Critics at the time of its first publication wrote that The Wanderer was terribly badly written and could not have been written by the author of the first three novels.

Thank you for your comment. This is certainly a very different perspective, but one I struggle to accept. Having read Fanny Burney's diaries, I have no difficulty in believing that she also wrote the novels that she talks about in her diaries.

DeleteHow would you explain all of the letters both Jane Austen and Frances Burney wrote to family and friends discussing their novels in the process of writing them? Was is all part of some mass conspiracy to save the face of one woman. Not to mention Austen and Burney do indeed have different writing styles and tones, so does this mean that Eliza suddenly changed how she wrote?

DeleteThese are very good questions and I await the answers with interest!

DeleteOf course this (Burney+Austen=de Feullide) seems preposterous, as anyone must feel who has read and loved reading "Evelina", Fanny's diaries and the superb, wonderfully comic novels of Jane Austen. Flighty little Eliza would've been altogether too much occupied to have been their author. It's another "Bacon wrote Shakepeare's plays"-type of myth - might sell a book or two... On the other hand, can we be sure Corneille did not ghost-write Molière's plays? Could one be a busy actor-manager and find the time to write such a body of seminal comedies? As well as the tranquillity to write, Jane Austen hoped her creations would be well enough received to bring financial success, which must have been a spur; though not in want, she certainly didn't have her cousin's ease where money was concerned.

DeleteI guess that it is almost impossible to prove that one person wrote something without any significant help from another, especially at a time when so many people wrote anonymously - especially women. However, I too find it impossible to believe that the same person wrote Evelina and Pride and Prejudice. The diaries and letters of the two authors and the way they refer to their books and characters leaves me confident that they wrote the books they are credited with.

DeleteBurney was the co-Keeper of the Robes with Elizabeth Schwellenberg, who was not her superior although she acted as if she were. Second Keeper is Joyce Hemlow's mistake.

ReplyDeleteThank you for pointing this out. Fanny's diaries read as if she is under Mrs Schwellenberg, but on rereading her appointment, it is as a replacement for Mrs Haggerdorn, one of the keepers of the Queen's robes. In his biography of Fanny Burney in the version of Fanny's diaries that I am looking at, Lord Macaulay refers to Mrs Schwellenberg as the chief keeper of the robes suggesting that Fanny was only the assistant or second keeper.

DeleteAnyone who has read Burney's journals knows how ridiculous Mr. Enoss's claim is. Nowadays, you'd be hard-pressed to find a critic who agrees that The Wanderer is badly written. The book, which was ahead of its time, has finally found its audience.

ReplyDeleteI haven't read The Wanderer, but I am very pleased to hear that it is not badly written, even though it was not very popular at the time. I will have to add it to my reading list!

Delete"Nowadays, you'd be hard-pressed to find a critic who agrees that The Wanderer is badly written."

ReplyDeleteThis shows how badly educated critics are nowadays. I doubt that many critics now would be well acquainted with literature in Ancient Greek, Latin, French and Italian, as most critics of the early 19th century were. The early nineteenth century critics were unanimous not only that "The Wanderer" was terribly badly written but also that it was by a different author than the first three novels. Readers of "The Wanderer" when it was published also believed it was a terribly bad book as many copies were returned and a very large number of copies were pulped. We can be sure from Fanny Burney's contemporary letters in the same dreadful writing style that "The Wanderer" was written by her, and so it is proved that the first three novels were by another author. All the circumstantial evidence points to Eliza de Feuillide being that author.

Among the numerous proofs that Eliza de Feuillide was a novelist is that she was praised as a great novelist in her poems by Lady Sophia Burrell, who was an accomplished poet and tragedian. This was before the novels of Jane Austen were published, and therefore must refer to the novels of Fanny Burney, the first two of which were published anonymously.

It is hard to rely on any evidence from the letters of Jane Austen as all but 200 out of 3000 were deliberately destroyed after her death. The most plausible reason for this destruction was to disguise who the real author was.