|

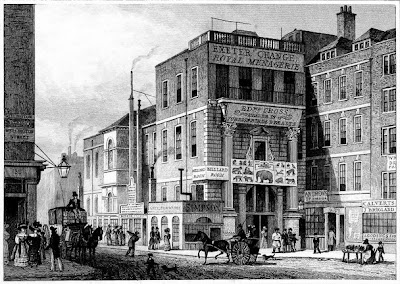

| The Exeter 'Change from London in the Nineteenth Century by Thomas H Shepherd (1829) |

The Exeter Exchange, popularly known as the Exeter ‘Change, was on the north side of the Strand in London. It was built on the site of Exeter House, a residence of the Earls of Exeter, from which it acquired its name. The building was designed to be a superior shopping venue, with an arcade in front, and originally housed small shops with lodgings above, but over time, the ground floor was taken over by businesses.

The Royal Menagerie

|

| The Royal Menagerie, Exeter 'Change from Ackermann's Repository (1812)3 |

From about 1773, the upper floors took on a new role, housing a menagerie formed by Mr Pidcock. On Pidcock’s death in about 1810, the menagerie passed to Stephani Polito and on his death in 1814, one of his employees, Edward Cross, took over the menagerie.

The menagerie displayed a wide variety of animals to the public in competition to the menagerie at the Tower of London.

The menagerie displayed a wide variety of animals to the public in competition to the menagerie at the Tower of London.

In 1812, the animals at the Exeter ‘Change included a Bengal tiger, a hyena, a lion, a jaguar, a sloth, a camel, monkeys, a hippopotamus, a rhinoceros, an elephant, an ostrich “said to weigh upwards of 200lbs and to be 11 feet high”, a cassowary, a pelican, “emews”, cranes, an eagle, cockatoos, elks, kangaroos and antelopes.2

|

| Advert from Ackermann's Repository (1814) |

The advert reads, I think:

Lord Byron at the Exeter ‘Change

Lord Byron was among the visitors to the Royal ‘Change. In an entry in his diary begun November 14 1813, he wrote:

Chunee the elephant

How much did it cost?Royal Menagrie, Exeter ‘Change

The numerous parties of distinction that daily visit the Royal Menagerie, Exeter ‘Change, is a well-merited reward to its celebrated Proprietor, for his spirited and indefatigable exertions, in procuring, for the inspection of the public, those remarkable and rare living objects of the first celebrity in natural history, which no other capital in Europe can boast of.The formidable Rhinoceros, which is grown so prodigiously since his arrival in 1810, as to be considered one of the largest ever seen, even in India, is so extremely rare, that many gentlemen have taken long and extensive excursions in its native country, without ever having an opportunity to see that animal; and his history, in many respects, is but very imperfectly known. Where it inhabits it is a dread to the human race, as well as to all beasts of the forest, being in strength inferior to none, and so protected, by nature, with his coat of mail, as to be capable of resisting the attacks of any other animal, and even the force of a musket-ball: but, what is more wonderful, in the adjoining den, in the same apartment, there is a fine large Male Elephant (indisputably one of the finest specimens of its species ever brought from India, and adorned with long ivory tusks); those, the two most formidable enemies in nature, are so closely united, and so reconciled, as to suffer to take their food from each other.The other apartments contain the Tapir, or Hippopotamus of the New World, that elegant quadruped, the Quagga, or Wild Horse of Ethiopia, the beautiful Nilghaw, from the interior of India, and the grand assemblage of Lions, Royal Tiger, Panther, Leopards, Ounce, Cervat, Hyaena, Ursine Sloth, Arabian Camel, Antelopes, Southern Ostrich, Grand Cassowary, the Royal Crown Bird, Vultures, and hundreds of other rare and interesting quadrupeds, and birds of the most exquisite plumage, all in fine health and condition, and so perfectly clean and secured, that the most timorous and delicate may approach them without fear or being annoyed. So desirable an exhibition is justly considered a great acquisition to the metropolis, and cannot fail of giving universal satisfaction.

|

| Details from Leigh's New Picture of London (1818) |

Lord Byron was among the visitors to the Royal ‘Change. In an entry in his diary begun November 14 1813, he wrote:

Two nights ago I saw the tigers sup at Exeter ‘Change. Except Veli Pacha’s lion in the Morea, who followed the Arab keeper like a dog, - the fondness of the hyaena for her keeper amused me most. Such a conversazione! – There was a ‘hippopotamus’ like Lord Liverpool in the face; and the ‘Ursine Sloth’ hath the very voice and manner of my valet – but the tiger talked too much. The elephant took and gave me my money again – took off my hat – opened a door – trunked a whip – and behaved so well, that I wish he was my butler. The handsomest animal on earth is one of the panthers; but the poor antelopes were dead. I should hate to see one here: - the sight of the camel made me pine again for Asia Minor.4

Chunee the elephant was the star attraction of the menagerie. After arriving in England in 1809, he performed on stage, delighting audiences “for forty successive nights at the Theatre Royal, Covent-Garden”2 and was often paraded in the street outside the menagerie.

But he was not a happy elephant and on 26 February 1826, he went out of control and killed one of his keepers in a fit of bad temper and was subsequently put down for safety reasons.

The end of the menagerie at the Exeter 'Change

After the death of Chunee, the popularity of the menagerie rapidly declined. Cross started a new menagerie at the Surrey Zoological Gardens, and around 1829 the Exeter ‘Change was demolished.

The end of the menagerie at the Exeter 'Change

After the death of Chunee, the popularity of the menagerie rapidly declined. Cross started a new menagerie at the Surrey Zoological Gardens, and around 1829 the Exeter ‘Change was demolished.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) Also known as the Exeter Change - the apostrophe is sometimes dropped.

(2) From Ackermann’s Repository (Jul 1812).

(3) There is some artistic licence in the print of the first floor of the Royal Menagerie, full details of which are given in the accompanying article in Ackermann's Repository.

(4) From Life, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron (1839).

(2) From Ackermann’s Repository (Jul 1812).

(3) There is some artistic licence in the print of the first floor of the Royal Menagerie, full details of which are given in the accompanying article in Ackermann's Repository.

(4) From Life, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron (1839).

Sources used include:

Byron, George Gordon, Baron and Moore, Thomas, Life, Letters and Journals of Lord Byron (1839)

Leigh, Samuel, Leigh's New Picture of London (London, 1818)

Shepherd, Thomas H, London in the Nineteenth Century, illustrated by a series of views (1829)

Thank you Rachel for this wonderful post which I had to share on my Lord Byron page...

ReplyDeleteBest wishes, Tee

Glad you enjoyed the post - the Lord Byron quote is very funny!

DeleteI think Messrs Pidcock. Polito & Cross can thank their lucky stars that there was no RSPCA back then

ReplyDeleteYes, I don't think the animals had much room. :(

DeleteBEING A PIDCOCK, I WAS INTERESTED IN FINDING A PICTURE BY GILLRAY THE MONKEY PIDCOCK DRESSED AS NAPOLEON

ReplyDeleteClearly Gillray was poking fun at Mr Pidcock's menagerie! Are you related to the Pidcock who once owned the menagerie?

DeleteNo.Iam Charles STEPHEN Polito.....

ReplyDeleteI got a golden watch from 1727 that was made in this street

ReplyDelete