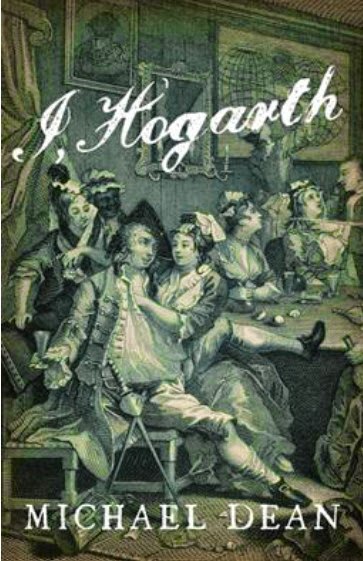

‘A work of fiction’

I, Hogarth is a very readable book which tells the story of William Hogarth, the famous Georgian painter and engraver. It vividly describes 18th century London and gives a background to many of the scenes that Hogarth represented in his work. Described as a ‘raucous novel of a raucous age’, in places I found it a little too coarse for my taste. It was easier to read than a traditional biography and gave me a real taste of what Hogarth was like. But at the end I had to ask, was it the right flavour?

The author’s note explains that I, Hogarth “is a work of fiction, so some real events have been bent to the demands of the narrative: others omitted altogether, others invented.” And therein lies my problem. I do not know which parts of what I have read were true, and which were not.

What was Hogarth really like?

|

| David Garrick and his wife, Eva-Maria Veigel by William Hogarth (1757-64) |

I am not an expert on William Hogarth. I know that he was a painter in the early Georgian period and that he produced several series of engravings on moral themes. I have seen some of his original work – his colourful portrait of David and Maria Garrick at The First Georgians exhibition and the original paintings of A Rake’s Progress in the Picture Room of Sir John Soane’s Museum. And of course, I have seen many of his prints, both on and offline.

Of the man I knew little. Dean depicts Hogarth as a man who started low and, through his own genius, built a successful career and married the daughter of the painter Sir James Thornhill. That much is history. But did Hogarth really frequent bawdy houses with such regularity and catch the pox? Did the man who painted pictures warning against the perilous life of the rake and the harlot have so few morals himself?

Fact or fiction?

The problem with a work of fiction based on fact is that it is impossible to separate the truth from the fiction. For example, I knew that the paintings of A Rake’s Progress had not gone up in flames, as it says in Dean’s book, as I had seen the originals. But what of A Harlot’s Progress? Did they burn as Dean says or was that made up too? A little research showed me that both sets of paintings really had been owned by William Beckford, and that A Harlot’s Progress had indeed been destroyed by a fire at Beckford’s home at Fonthill Splendens in Wiltshire in 1755.

|

| A Harlot's Progress, Plate 1 by William Hogarth (1732) © British Museum |

I have to conclude that though this was, for the most part, an entertaining read, I find the genre of a fictional account of a historical person’s life confusing and dissatisfying. As a historian, I want to know fact. I don’t mind that fact being acted out for me with scenes that could have been true, but to change the truth, without any indication of what has been altered in the author’s note, leaves me with too many unanswered questions.

Have you seen the tv-movie "A Harlot's Progress" (2006)? Quite interesting if you haven't seen it :)

ReplyDeleteNo, I haven't. I'll have to watch out for that one. Thanks.

DeleteIt stars that funny little actor who played Robert Cecil in Helen Mirren's Elizabeth, I think he also played one of the Fox brothers in the period drama "The Aristocrats". It's on YouTube :)

Delete