|

| St James's Palace, London (2012) |

|

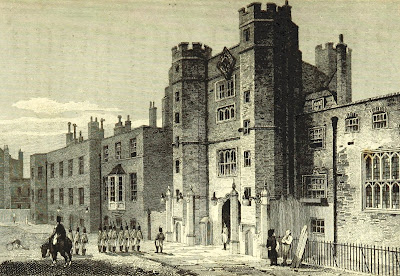

| View of St James's Palace during the time of Queen Anne from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

In The history of the Royal Residences, Pyne wrote that after George III’s accession to the throne:

The court was immediately removed to St James’s Palace, the king having issued an order for holding a drawing-room there every Thursday and Sunday.1

Well-dressed persons who wish to see the nobility and other persons of distinction go to court, on drawing-room days, may easily obtain admission to the ante-room, by permission of the officer of the guard, the yeomen, or other persons in waiting, provided application be made before the court begins. On birth-days, admission may be obtained to the gallery of the ball-room, either by the ticket of a peer, or the introduction of a page, or any person in the royal household. Admission may also be obtained to the Lord Chamberlain's box, but it is necessary to be full dressed. In this, as in most other cases, a small fee, properly applied, is the readiest and most independent passport.2

|

| St James's Palace from The History of he Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

George III and Queen Charlotte were married at St James’s Palace on 8 September 1761. George III bought Buckingham House, what is now Buckingham Palace, for his wife, and this became the main London residence for the royal family. However, it was at St James’s Palace, not Buckingham House, that George III’s first child, the future George IV, was born on 12 August 1762.

Pyne recorded that:

For the gratification of the public, it was announced, before the young prince was twelve days old, that his royal highness was to be seen at St. James’s from one until three o’clock on drawing-room days.3

|

| Princess Caroline of Brunswick by Sir Thomas Lawrence (c1804) © National Portrait Gallery, London George IV when Prince of Wales by John Hoppner (1792) © The Wallace Collection |

Old and New London stated:

On the 22nd of January, 1809 … about half-past two in the morning, a fire was discovered in St James's Palace, near the King's back stairs. The whole of the private apartments of the Queen, those of the Duke of Cambridge, the King's court, and the apartments of several persons belonging to the royal household, were destroyed; the most valuable part of the property was preserved.4

In 1808 the south-eastern wing of the building was destroyed by fire, and it still continues a vast mass of ruins; the state apartments were, however, uninjured, and the court of George the Third and his Queen were held here. It is said this palace will speedily be pulled down, and on the spot facing St James's Street a grand triumphal arch will be erected, to commemorate the victories of the late war, and to form a grand passage into St James's Park.5

|

| The German Chapel or Queen's Chapel, St James's Palace from The History of he Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

The Picture of London for 1818 wrote:

The other parts of St James's Palace are very irregular in their form, consisting chiefly of several courts. Some of the detached apartments are occupied by the Duke of Cumberland and the Duke of Clarence, others by the king's servants, and others are granted as a benefit to their occupiers.6

|

| St James's Palace from The Beauties of England and Wales Vol X by EW Brayley, J Nightingale and J Brewer (1814) |

This royal residence, it must be acknowledged, does not wear an appearance suited to the character of the sovereign who there holds his court; or to the power, wealth, and extent of that empire which he governs. Foreigners, accustomed to view the magnificence of the continental palaces, never fail to express their astonishment at its unappropriate exterior: and some of their travelling writers have almost doubted the affection of the English people for their kings, by permitting them to inhabit a structure so inferior in its figure to the proud character of the metropolis in which it is situated, and to the high claims of the monarch of the most opulent nation of the world.7

The external appearance of this palace is inconsiderable, yet certainly not mean. It is a brick building; that part in which the rooms of state are, being only one story, gives it a regular appearance on the outside.8

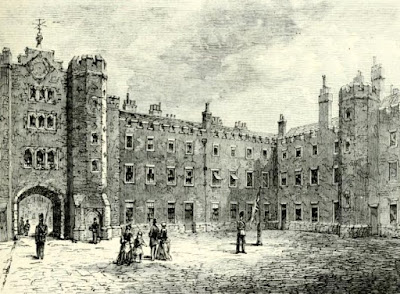

It is an irregular, heavy, brick building, but of considerable extent, and is not relieved by any ornaments. In the front which presents itself to St James's-street, is a Gothic arched gateway, with embattled towers, which leads into a square court, where the company of guards on duty is daily relieved, and where it parades in form on state days: the colours are fixed in the center of it. On the south and west sides are handsome colonnades, forming a covered passage to the great staircase, which is at the south-west corner of it. There are two other courts beyond it, besides an inhabited open space, called the Stable-yard, but they do not deviate from the ordinary appearance of the rest of the structure; though some of their apartments have an agreeable view over the garden, as well as St James's and the Green parks.9

|

| Courtyard of St James's Palace in 1875 from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

The writer of The Microcosm of London felt the interior of the palace was much superior to its exterior:

The Palace … has, for many years, been employed merely as the scene of the royal drawing-rooms on court days; but, with all its disadvantages as to exterior appearance, the number, succession, and proportions of its apartments are such, for every display of regal state and ceremonial connected with a court, that it may be said, we believe, to rival the most admired palaces of foreign princes.10

On the west side of the first and principal court is the chapel royal, which is the same as belonged to the ancient hospital; and, ever since the demolition of that building, has been converted to the use of the royal family.

Before the King made Windsor the principal place of his residence, he always went, attended by the royal family, in great state, to the chapel on Sundays, and after divine service there was a regular drawing-room.11

It is oblong in plan, and plain, and has nothing about it to call for particular mention, excepting, perhaps, the ceiling, which is divided into small painted squares, the design of which was executed by Hans Holbein.12

The Microcosm of London wrote:

The state apartments are of handsome proportions, and range in commodious succession; but they do not contain those superb decorations or splendid furniture, which might be expected to adorn the residence of George the Third.13

The State Apartments, in the south front of the Palace, face the garden and St James's Park. The sovereign enters by the gate on this side; it was here, on the 2nd of August, 1786, that Margaret Nicholson made an attempt to assassinate George III as he was alighting from his carriage.14

The entrance to these rooms is by the staircase that opens into the principal court next Pall-Mall. The guard-rooms are at the top of it: that to the left is called the Queen's, that to the right is the King's, which leads to the apartments, and is occupied by the yeomen of the guard.15

Immediately beyond the latter is the King's presence-chamber, where the band of pensioners range themselves on court-days.16

|

| King's Presence Chamber, St James's Palace from The History of he Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

That is a mere passage-room to the principal apartments, of which there are five, opening into each other, and fronting the park. The center room is called the privy-chamber, with a canopy of state, which is used on one peculiar occasion that very seldom occurs; when his Majesty receives an address from the people called Quakers.

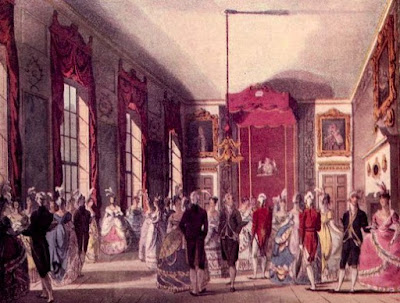

On the right are two drawing-rooms en suite: the first serves as an antichamber to the latter, which is called the grand council-chamber, and where the councils of state were held when this Palace was inhabited by the royal family. At the upper end is a canopy, beneath which the King receives addresses delivered in form to the throne. In the center of the room is suspended a large chandelier of silver gilt. The canopy of the throne was put up on account of the union of the kingdoms of Great Britain and Ireland, and was displayed on the first drawing-room after that event, which happened to be the Queen's birth-day. It is of crimson velvet, bordered with a broad gold lace, and enriched with embroidered crowns, set with fine pearls. The shamrock, the badge of the Irish nation, forms one of the decorations of the crown, and is accurately executed. It is the apartment in which their Majesties hold their drawing-rooms.17

|

| A drawing room at St James's Palace from The Microcosm of London by R Ackermann and W Combe (1808-10) |

To the left of the center room, are two levee-rooms; the first serving as an antichamber to the other. They retained their old and worn-out furniture, till the marriage of the Prince of Wales, when they were fitted up in their present state. The walls are now covered with very beautiful tapestry, whose colours are quite fresh, though it was fabricated for Charles II. It had never been put up, but had lain forgotten, during the long interval of so many years, among the useless lumber of the Palace, till it was accidentally discovered in an old chest, some time previous to the occasion which suggested the appropriate use that has been made of it. In the grand levee-room a very superb bed was put up at the same time. The furniture is of crimson velvet, manufactured in Spitalfields.18

When a drawing-room is held, a person attends here to receive the cards containing the names of the parties to be presented, a duplicate being handed to the lord in waiting, to prevent the presentation of persons not entitled to that privilege.19

The "Royal Closet" is the name conventionally given to the room in which the Queen gives audiences to ambassadors, and also receives an address annually on her birthday from the clergy of the Established Church.20

The ball-room is in that part of the Palace which stretches on to the Stable-yard. It is of considerable dimensions, with ranges of seats above each other for the court: there is a gallery at one end for the musicians, and two side galleries for the spectators. The area is for the dancers and the royal circle. It used to be employed for the court balls on birth-nights and other royal festivities, when the assembled company formed a magnificent and splendid spectacle; but it does not in itself possess the least decoration. It is painted of one colour; nor does it appear to have been refreshed by the brush for many a year. But these festal scenes have been omitted for many seasons; and indeed the Palace itself is only used for purposes of state.21

Pyne wrote:

The old bedchamber is the last room at the east end of the south front of St James’s Palace, looking into the garden; the apartments east of which were destroyed by the fire that happened there a few years since.22

|

| Old Bedchamber, St James's Palace from The History of he Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| Kitchen, St James's Palace from The History of he Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

St James’s Palace is still a working palace today and houses various royal officials and is the London residence of some members of the royal family. The Queen’s Chapel is occasionally open to the public.

|

| St James's Palace (2012) |

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) Pyne, WH, The History of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House and Frogmore (1819).

(2) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813).

(3) Pyne op cit.

(4) Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878, London) Vol 4.

(5) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818).

(6) Ibid.

(7) Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(8) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(9) Ackermann op cit.

(10) Ackermann op cit.

(11) Ackermann op cit.

(12) Walford op cit.

(13) Ackermann op cit.

(14) Walford op cit.

(15) Ackermann op cit.

(16) Ackermann op cit.

(17) Ackermann op cit.

(18) Ackermann op cit.

(19) Walford op cit.

(20) Walford op cit.

(21) Ackermann op cit.

(22) Pyne op cit.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Brayley, Edward Wedlake, Nightingale, J and Brewer, J, The Beauties of England and Wales Vol X part II (London and Middlesex)(1814)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Pyne, WH, The History of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House and Frogmore (1819)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878, London) Vol 4

Royal Residences website

All photos © RegencyHistory.net

Fascinating! Thank you for sharing this marvellously informative post.

ReplyDeleteLovely photos and great information. I got to visit England this summer. A pity I was unable to view St. James's Palace, although I did get to visit many stately homes!

ReplyDeleteThanks for researching all of this great information!

ReplyDelete