|

| St George's Hanover Square - the most fashionable church in Regency London |

There was a rush to get married before the Act came into force and the registers of St George’s Chapel state that 1,136 marriages took place between October 1753 and March 1754 including 61 on the 24 March 1754.

If either of the couple were under the age of 21 years and previously unmarried, then a parent or guardian of the underage party could forbid the banns. However, if they failed to object at the time the banns were read, they could not later object to the marriage.

The marriage ceremony could only take place at one of the places where the banns were read. It had to be witnessed by two people in addition to the minister taking the ceremony, and the marriage register had to be signed by the minister, the witnesses and the two parties getting married.

This was by far the most common way of getting married.

Before the licence could be issued, one of the couple or someone acting on their behalf had to submit a sworn statement or allegation that there was no impediment of kindred or alliance to the marriage, and if one or both parties were underage and previously unmarried, that they had the consent of their parent or guardian. There was also a requirement for the groom or someone acting on his behalf to enter a bond where a substantial amount of money would be forfeited if an impediment existed.

The marriage had to take place in the church or chapel of the parish where one of the couple had been residing for at least four weeks. As with banns, the wedding had to take place in front of two witnesses who signed the register along with the minster and the couple.

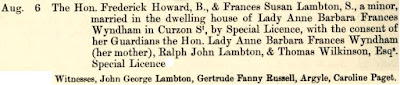

| Entry in the marriage register of St George's Hanover Square for a marriage by licence in 1815. This example is for the marriage of a minor and states that her father's consent had been obtained. |

Hardwicke’s Marriage Act was amended several times, most importantly by the Act of July 1823. The new stipulations which took effect on 1 November 1823 included:

• The marriage had to take place within three months of the banns being completed or from the date the licence was granted.

• The marriage had to take place between 8 o’clock and 12 noon, unless by special licence.

• The period of residency for the granting of a licence was reduced to 15 days.

• It was no longer necessary to enter into a separate bond when applying for a licence.

Runaway marriages

|

| Travelling chariot at the blacksmith's shop, Gretna Green |

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. From An Act for the better preventing of clandestine Marriages (1753)

2. All quotes from the marriage registers of St George’s Hanover Square are from the transcriptions edited by John Chapman (see full details below).

Sources used include:

An Act for amending the Laws respecting the Solemnization of Marriages in England [18th July 1823]

An Act for the better preventing of clandestine Marriages (1753)

Chapman, John H (ed) The Register book of marriages belonging to the Parish of St George, Hanover Square in the County of Middlesex Vol 3 1810-1823 (1896)

Clinch, George, Mayfair and Belgravia: being an historical account of the parish of St George, Hanover Square (1892)

Familysearch.org website

Lambeth Palace Research guide