|

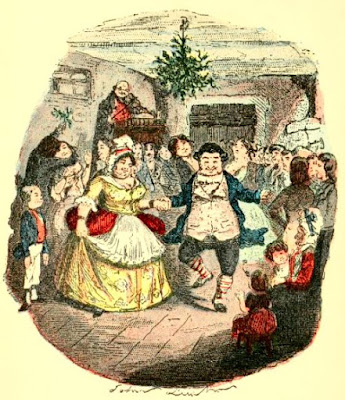

| Mr Fezziwig's Ball by John Leech from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1920 reprint of original 1843 edition) |

A Christmas Carol was published on 19 December 1843 and was a huge success. It is still very popular today and numerous adaptations have been made (two of which I’ve already watched this Christmas – Scrooged starring Bill Murray and A Christmas Carol starring Patrick Stewart). Some credit Dickens with bringing Christmas back into fashion, but is this true? I thought I would see what I could find in contemporary sources and novels about Christmas celebrations in the late Georgian and Regency periods.

|

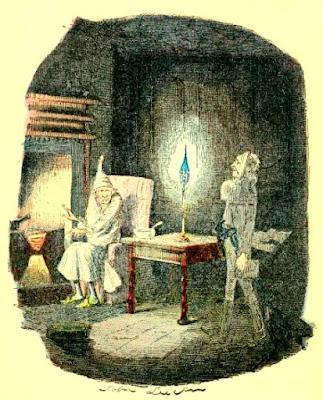

| Marley's Ghost by John Leech from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1920 reprint of original 1843 edition) |

Bank Holidays were first introduced by an act in 1871 but Christmas Day was not included as, along with Good Friday, it was already traditionally accepted as a public holiday in Britain. There is evidence that this holiday was observed in late Georgian England. The Persian ambassador, Mirza Abul Hassan, visiting England in 1809-10, wrote in his journal on Monday 25 December 1809:

This morning a messenger brought a note from Sir Gore Ouseley to say that Lord Wellesley had forgotten that today is one of their holidays and that it would not be possible for him to visit me. He would see me tomorrow night. In reply I wrote: ‘Such an excuse is unacceptable.’1

The Persian ambassador clearly did not understand the necessity for a holiday on Christmas Day!

It would appear that the theatres were closed on Christmas Day. The Theatrical Register for December 1809 showed that the theatre was not open on Sundays or on Christmas Day.2

It would appear that the theatres were closed on Christmas Day. The Theatrical Register for December 1809 showed that the theatre was not open on Sundays or on Christmas Day.2

Did people attend a church service on Christmas Day?

|

| St George's, Hanover Square from Ackermann's Repository (1812) |

The weather was most favourable for her; though Christmas Day, she could not go to church. Mr. Woodhouse would have been miserable had his daughter attempted it, and she was therefore safe from either exciting or receiving unpleasant and most unsuitable ideas. The ground covered with snow, and the atmosphere in that unsettled state between frost and thaw, which is of all others the most unfriendly for exercise, every morning beginning in rain or snow, and every evening setting in to freeze, she was for many days a most honourable prisoner.3

Harriet Leveson-Gower, Lady Granville, daughter of Georgiana Cavendish, Duchess of Devonshire, spent Christmas 1824 in Brighton with the king, George IV. She wrote:

On Christmas Day we processed into the chapel, where the service was really divine, but what with heat and emotion very overpowering.4

Perhaps surprisingly, the marriage registers of St George’s Hanover Square show that people could get married on Christmas Day.5

In Mansfield Park, Edmund Bertram expected to take orders at Christmas and wrote:

On the 23rd he was going to a friend near Peterborough, in the same situation as himself, and they were to receive ordination in the course of the Christmas week.6

Was Christmas a time for family?

Jane Austen certainly thought so. Christmas was a time of the year when the whole family could be together. Many gentlemen’s sons (and sometimes daughters) were sent away to be educated at boarding schools such as Eton, and the Michaelmas Term ran from late September or October until Christmas.

|

| Eton College from Picturesque Views of the River Thames by S Ireland (1792) |

Immediately surrounding Mrs Musgrove were the little Harvilles, whom she was sedulously guarding from the tyranny of the two children from the Cottage, expressly arrived to amuse them. On one side was a table occupied by some chattering girls, cutting up silk and gold paper; and on the other were tressels and trays, bending under the weight of brawn and cold pies, where riotous boys were holding high revel; the whole completed by a roaring Christmas fire, which seemed determined to be heard, in spite of all the noise of the others. Charles and Mary also came in, of course, during their visit, and Mr Musgrove made a point of paying his respects to Lady Russell, and sat down close to her for ten minutes, talking with a very raised voice, but from the clamour of the children on his knees, generally in vain. It was a fine family piece.7

In Emma, Emma’s sister and husband were coming to stay at Hartfield for Christmas. Emma commented:

It is unfortunate that they cannot stay longer—but it seems a case of necessity. Mr John Knightley must be in town again on the 28th, and we ought to be thankful, papa, that we are to have the whole of the time they can give to the country, that two or three days are not to be taken out for the Abbey. Mr Knightley promises to give up his claim this Christmas—though you know it is longer since they were with him, than with us.8

In Pride and Prejudice, Mr and Mrs Gardiner arrived to stay with the Bennet family for Christmas:

On the following Monday, Mrs Bennet had the pleasure of receiving her brother and his wife, who came as usual to spend the Christmas at Longbourn.9

After becoming betrothed to Mr Darcy, Elizabeth Bennet wrote to her Aunt Gardiner:

Mr Darcy sends you all the love in the world that he can spare from me. You are all to come to Pemberley at Christmas.9

|

| Lyme Park, Cheshire - Pemberley in the BBC's 1995 adapation of Pride and Prejudice |

For some, Christmas was spent away from home with friends. Horace Walpole wrote on 30 December 1761:

I have been my out-of-town with lord Waldegrave, Selwyn, and Williams; it was melancholy the missing poor Edgecumbe, who was constantly of the Christmas and Easter parties.10

Maria Edgeworth spent Christmas Day 1807 at Pakenham Hall, the home of Kitty Pakenham, who later became the wife of Arthur Wellesley, Duke of Wellington. Maria wrote:

A merry Christmas to you, my dear Henry and Sneyd! I wish you were here at this instant, and you would be sure of one; for this is really the most agreeable family and the pleasantest and most comfortable castle I ever was in. We came here yesterday – the we being Mr and Mrs Edgeworth, Honora, and ME. A few minutes after we came, arrived Hercules Pakenham – the first time he had met his family since his return from Copenhagen.’11

Harriet Leveson-Gower, Lady Granville, described the party gathered in Brighton for Christmas 1824:

We arrived here on the 24th in time for dinner. The King received us more than graciously. I never saw him in such health and spirits. He scarcely ever sits down or is still for a moment, but allows us. No legs but royal ones could otherwise endure. The company assembled were the Duke of York, who adores us, breakfasts en trio with us every morning, says Wherstead is the best house in England, and my toilette the most perfect. Partiality could no further go. The Duke of Clarence, the Duchess, a very excellent, amiable, well-bred little woman, who comes in and out of the room a ravir, with nine new gowns (the most loyal of us not having been able to muster above six), moving a la Lieven, independent of her body. Lord and Lady Erroll with faces like angels, that look as if they ought to have wings under their chins. She is a domestic, lazy, fat woman, excédée with curtseying and backsliding. Lord and Lady Maryborough, a very agreeable woman, with a fine back and very plausible ugliness. The usual Dukes and gentlemen-in-waiting. Lord Exeter, who pays no attention to Lady Exeter, who, nevertheless, is as handsome and as delightful as ever.12

Jane Austen referred to the gaieties of the Christmas season in her novels. In Emma, Mr Elton noted that:

This is quite the season indeed for friendly meetings. At Christmas every body invites their friends about them, and people think little of even the worst weather. I was snowed up at a friend's house once for a week. Nothing could be pleasanter. I went for only one night, and could not get away till that very day se'nnight.13

In Persuasion, Mary moaned to her sister Anne Elliot:

We have had a very dull Christmas; Mr and Mrs Musgrove have not had one dinner party all the holidays. I do not reckon the Hayters as anybody. The holidays, however, are over at last: I believe no children ever had such long ones. I am sure I had not.14

In Mansfield Park, Miss Crawford is eager for news of Edmund. She asked:

Was his letter a long one? Does he give you much account of what he is doing? Is it Christmas gaieties that he is staying for? She continued: Oh! if he wrote to his father; but I thought it might have been to Lady Bertram or you. But if he wrote to his father, no wonder he was concise. Who could write chat to Sir Thomas? If he had written to you, there would have been more particulars. You would have heard of balls and parties.15

In Pride and Prejudice, on setting out to follow her brother to London, Caroline Bingley wrote to Jane Bennet:

Many of my acquaintances are already there for the winter; I wish that I could hear that you, my dearest friend, had any intention of making one of the crowd—but of that I despair. I sincerely hope your Christmas in Hertfordshire may abound in the gaieties which that season generally brings, and that your beaux will be so numerous as to prevent your feeling the loss of the three of whom we shall deprive you.16

In Sense and Sensibility, Sir John described Willoughby:

‘He is as good a sort of fellow, I believe, as ever lived,’ repeated Sir John. ‘I remember last Christmas at a little hop at the park, he danced from eight o'clock till four, without once sitting down.’17

Did people play games at Christmas?

Fanny Burney recorded an instance of playing Christmas games in her diary for December 1785. She was teaching games to a little girl when they were disturbed by the entrance of the king, George III:

After dinner, while Mrs Delany was left alone, as usual, to take a little rest—for sleep it but seldom proves—Mr B Dewes, his little daughter, Miss Port, and myself, went into the drawing-room. And here, while, to pass the time, I was amusing the little girl with teaching her some Christmas games, in which her father and cousin joined, Mrs Delany came in … The Christmas games we had been showing Miss Dewes, it seemed as if we were still performing, as none of us thought it proper to move, though our manner of standing reminded one of “Puss in the corner.” Close to the door was posted Miss Port; opposite her, close to the wainscot, stood Mr Dewes; at just an equal distance from him, close to a window, stood myself. Mrs.Delany, though seated, was at the opposite side to Miss Port; and his majesty kept pretty much in the middle of the room. The little girl, who kept close to me, did not break the order, and I could hardly help expecting to be beckoned, with a PUSS! PUSS! PUSS! to change places with one of my neighbours.18

In Emma, Mrs Elton is scornful of the game suggested by Frank Churchill:

I really cannot attempt—I am not at all fond of the sort of thing. I had an acrostic once sent to me upon my own name, which I was not at all pleased with. I knew who it came from. An abominable puppy!—You know who I mean (nodding to her husband). These kind of things are very well at Christmas, when one is sitting round the fire; but quite out of place, in my opinion, when one is exploring about the country in summer.19

Did they give to the poor?

Wilson spoke of the generosity of the actress Harriot Mellon’s mother:

And when some kind patron would send her a Christmas or Easter present in money, a portion of it always was devoted to the purchase of common clothing for infants, or to materials for a dinner to indigent persons in her parish.20

Watkins wrote of Queen Charlotte in 1800:

At the beginning of October the royal family left the coast for Windsor, where Her Majesty kept the Christmas-day following in a very pleasing manner. Sixty poor families had a substantial dinner given them; and in the evening the children of the principal families in the neighbourhood were invited to an entertainment at the Lodge.21

Did they give each other presents?

Harriet Leveson-Gower, Lady Granville, wrote about Lady Conyngham’s Christmas presents in 1824:

I went after it to Lady Conyngham, and saw her Christmas gifts, which made my mouth water, and made me almost wish for a situation. A magnificent cross, seized from the expiring body of a murdered bishop in the island of Scio. An almanack, gold with flowers embossed on it of precious stones. A gold melon, which upon being touched by a spring falls into compartments like the quarters of an orange, each containing different perfumes. I returned like Aladdin after the cave, only empty-handed, which, I believe, he was not.22

The future Queen Victoria wrote in her diary for Christmas Eve, 1832:

Mamma gave me a lovely pink bag which she had worked with a little sachet likewise done by her; a beautiful little opal brooch and earrings; books, some lovely prints, a pink satin dress and a cloak lined with fur. Aunt Sophia gave me a dress which she worked herself, and Aunt Mary a pair of amethyst earrings. Lehzen a lovely music book. Victoire a very pretty white bag worked by herself and Sir John a silver brush. I gave Lehzen some little things and Mamma gave her a writing ¬table. We then went to my room where I had arranged Mamma’s table. I gave Mamma a white bag which I had worked, a collar and a steel chain for Flora and an annual; Aunt Sophia a pair of turquoise earrings; Lehzen, a little white and gold pin cushion and a pin with two little gold hearts hanging to it. Sir John, flora and a book holder and an annual. Mamma then took me up into my bedroom with all the ladies. There was my new toilet table with a white muslin cover over pink of all my silver things standing on it with a fine new looking glass. I stayed up till ½ past 9. The dog went away again to the doctor for her leg. I saw good Louis for an instant and she gave me a lovely little wooden box with bottles. I was soon in bed and asleep.23

Did they have special Christmas food?

|

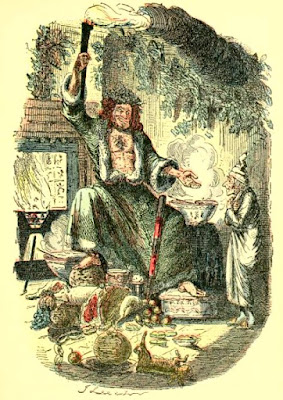

| Ghost of Christmas Present by John Leech from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1920 reprint of original 1843 edition) |

Lay pretty long in bed, and then rose, leaving my wife desirous to sleep, having sat up till four this morning seeing her mayds make mince-pies. I to church, where our parson Mills made a good sermon. Then home, and dined well on some good ribbs of beef roasted and mince pies; only my wife, brother, and Barker, and plenty of good wine of my owne, and my heart full of true joy; and thanks to God Almighty for the goodness of my condition at this day.24

Wilson also referred to mince pies when talking of the superstitious rituals that Harriot Mellon’s mother adhered to:

Mrs Entwisle had brought her up with the firm belief in the necessity of complying with the superstitious customs attached to certain days, the omission of which would infallibly be followed by ill luck; and therefore, the Christmas mince-pie, Shrove-Tuesday pancakes, Easter tansy-pudding, or Michaelmas-goose, must be tasted, though in ever so small a quantity, nay, even though disagreeable to the partaker, as was her own case respecting the Michaelmas dainty.25

On 16 December 1766, Horace Walpole wrote to his friend George Montagu:

Thank you for your offer of a do; you know, when I dine at home here, it is quite alone, and venison frightens my little meal; yet, as half of it is designed for dimidium animce meee Mrs Clive (a pretty round half), I must not refuse it; venison will make such a figure at her Christmas gambols! only let me know when and how I am to receive it, that she may prepare the rest of her banquet; I will convey it to her.26

|

| Scrooge and Bob Cratchit by John Leech from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1920 reprint of original 1843 edition) |

In his journal of his residence in Great Britain in 1810-11, Louis Simond refers to houses decorated with greenery at Christmas:

The villages along the road are in general not beautiful, the houses very poor indeed; the walls old and rough, but the windows generally whole and clean; no old hats or bundles of rags stuck in as in America, where people build, but do not repair. Peeping in, as we pass along, the floors appear to be a pavement of round stones like the streets— a few seats, in the form of short benches — a table or two — a spinning-wheel — a few shelves — and just now (Christmas,) greens hanging about.27

Did they have Christmas trees?

Christmas trees did not become widespread in England until after 1848 although Queen Charlotte had a Christmas tree from at least 1800. You can read more about this on my blog: Did they have Christmas trees in the Regency?

|

| Christmas tree at Windsor Castle from The Illustrated London News Christmas supplement (1848) |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Hassan Khan, Mirza Abul, A Persian at the Court of King George 1809-10, edited by Margaret Morris Cloake (1988)

2. The Gentleman's Magazine Supplement July-December 1809

3. Austen, Jane, Emma (1815)

4. Granville, Harriet, Countess, Letters of Harriet, Countess Granville 1810-1845 (1894)

5. Chapman, John H (ed) The Register book of marriages belonging to the Parish of St George, Hanover Square in the County of Middlesex Vol 3 1810-1823 (1896)

6. Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814)

7. Austen, Jane, Persuasion (1817)

8. Austen, Jane, Emma (1815)

9. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

10. Walpole, Horace, Correspondence of Horace Walpole with George Montagu (1837)

11. Edgeworth, Maria, A Memoir of Maria Edgeworth with a selection from her letters (1867)

12. Granville, Harriet, Countess, Letters of Harriet, Countess Granville 1810-1845 (1894)

13. Austen, Jane, Emma (1815)

14. Austen, Jane, Persuasion (1817)

15. Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814)

16. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

17. Austen, Jane, Sense and Sensibility (1811)

18. Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett (1842)

19. Austen, Jane, Emma (1815)

20. Wilson, Mrs Cornwell Baron, Memoirs of Miss Mellon, afterwards Duchess of St Albans (1886)

21. Watkins, John, Memoirs of her most excellent majesty Sophia-Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain (1819)

22. Granville, Harriet, Countess, Letters of Harriet, Countess Granville 1810-1845 (1894)

23. Queen Victoria’s journals online

24. Samuel Pepys diary online

25. Wilson, Mrs Cornwell Baron, Memoirs of Miss Mellon, afterwards Duchess of St Albans (1886)

26. Walpole, Horace, Correspondence of Horace Walpole with George Montagu (1837)

27. Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 (1815)

Sources used include:

Austen, Jane, Emma (1815)

Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814)

Austen, Jane, Persuasion (1817)

Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

Austen, Jane, Sense and Sensibility (1811)

Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett (1842)

Chapman, John H (ed) The Register book of marriages belonging to the Parish of St George, Hanover Square in the County of Middlesex Vol 3 1810-1823 (1896)

Edgeworth, Maria, A Memoir of Maria Edgeworth with a selection from her letters (1867)

Granville, Harriet, Countess, Letters of Harriet, Countess Granville 1810-1845 (1894)

Hassan Khan, Mirza Abul, A Persian at the Court of King George 1809-10, edited by Margaret Morris Cloake (1988)

Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 (1815)

The Gentleman's Magazine Supplement July-December 1809

Walpole, Horace, Correspondence of Horace Walpole with George Montagu (1837)

Watkins, John, Memoirs of her most excellent majesty Sophia-Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain (1819)

Wilson, Mrs Cornwell Baron, Memoirs of Miss Mellon, afterwards Duchess of St Albans (1886)

Queen Victoria’s journals online

Samuel Pepys diary online