|

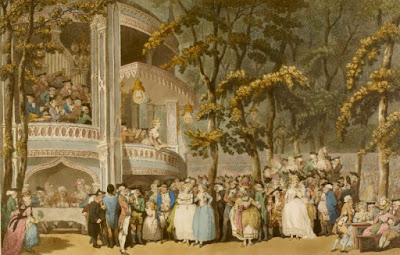

| Vauxhall Gardens from The Microcosm of London (1808-10) |

Vauxhall Gardens appear in numerous novels written in the Georgian period, such as Evelina and Cecilia by Fanny Burney and The Expedition of Humprhy Clinker by Tobias Smollett – the source of the following excerpt:

Image to yourself, my dear Letty, a spacious garden, part laid out in delightful walks, bounded with high hedges and trees, and paved with gravel; part exhibiting a wonderful assemblage of the most picturesque and striking objects, pavilions, lodges, groves, grottoes, lawns, temples and cascades; porticoes, colonnades, and rotundas; adorned with pillars, statues, and paintings: the whole illuminated with an infinite number of lamps, disposed in different figures of suns, stars, and constellations; the place crowded with the gayest company, ranging through those blissful shades, or supping in different lodges on cold collations, enlivened with mirth, freedom, and good humour, and animated by an excellent band of music.1

William Makepeace Thackeray’s Vanity Fair published in 1848, but set earlier in the century, also includes a scene played out in the famous Vauxhall Gardens. Unsurprisingly, historical romance authors today have continued the tradition and many Georgian and Regency romances include passages set in Vauxhall.

I am no exception. Both A Perfect Match and A Reason for Romance include scenes set in Vauxhall Gardens. What is it about Vauxhall Gardens that draws us in and compels us to use it as a backdrop for our writing?

|

| Vauxhall from Vauxhall Illustrated: Scrapbook of miscellaneous British 18th and 19th century prints (1883) © The Metropolitan Museum of Art DP259953 |

Vauxhall Gardens were pleasure gardens situated in Lambeth, Surrey, south of the River Thames, not far from where Vauxhall Bridge is today. Although this is now very much part of London, during the Georgian period, this was a rural area. The gardens were a popular place to go to breathe fresher air and be entertained outside, not just for the gentry, but for anyone who could pay the entrance price.

This was one of the attractions of Vauxhall – the cross-section of society to be found there – and it is one of the reasons that it is such a good site for action in a novel to unfold. It was a place where the nobility could rub shoulders with shopkeepers and merchants. It also attracted some of the less desirable elements of society such as pickpockets and prostitutes. Anything could happen at Vauxhall.

When were Vauxhall Gardens fashionable?

The Spring Gardens were established at Vauxhall shortly after the Restoration in 1660 and were visited by many celebrated people including John Evelyn and Samuel Pepys. However, it was not until Jonathan Tyers leased the gardens in 1729 that they began to be developed into the famous pleasure gardens. The newly refurbished gardens were opened in 1732 with a grand Ridotto al Fresco.

Over the years, the fortunes of the gardens went up and down, their profitability adversely affected by bad weather and how their rivals, like Ranelagh Gardens, were doing. Although at their most popular before 1786, they were still visited by thousands of people every year during the Regency.

The Picture of London for 1810 claimed ‘from five thousand to sixteen thousand well-disposed persons are occasionally present.’2

They attained the accolade of being called The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall, in 1822. The coming of the railways, allowing people to travel out of town, and the gardens’ inability to attract the Victorian public, finally led to their closure in 1859. Sadly, all that remains are the street names and a few placards in the park depicting the pleasure gardens as they once were.

As you read this post, it is important to keep in mind the long period of time during which Vauxhall Gardens operated as opening times, prices, buildings and entertainments were continually changing.

|

| Vauxhall Pleasure Gardens (2012) |

When was Vauxhall open?

The Vauxhall season was typically from May to August but opening and closing dates varied and the season was occasionally extended into September if the weather was good. The opening days also varied. During the early years, Vauxhall was open every day of the week, but Sunday opening was stopped in the 1760s. According to The Microcosm of London (1808-10), at that time, Vauxhall was only open three nights a week:

These gardens are opened for the season about the latter end of May, and continue their amusements for about three months. Company is admitted three nights in the week, Mondays, Wednesdays, and Fridays.3

Vauxhall was an evening entertainment, primarily to be enjoyed after dark when the lamps had been lit, but at some points in the gardens’ history, a concert would be given in the daylight, from about 5pm.

In Fanny Burney’s novel of the same name, Evelina describes how her party argued about when to go to the gardens:

There were twenty disputes previous to our setting out; first, as to the time of our going: Mr. Branghton, his son, and young Brown, were for six o’clock; and all the ladies and Mr. Smith were for eight; the latter, however, conquered.4

How much did it cost?

|

| Vauxhall season ticket by Hogarth (Summer) from London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century by W & AE Wroth (1896) |

The original price of admission to these gardens was one shilling, but of late years it has been raised to two shillings, (on gala nights three shillings,) a sum comparatively very trifling, when we consider the great nightly expenditure of the proprietors to render their property convenient and attractive.5

However, it appears that The Picture of London was out of date. The Microcosm of London (1808-10) wrote that ‘the price of admission is three shillings and sixpence.’6

Special events cost more. The gardens also offered season tickets which gave entry for two for the whole season. Each year, the silver season ticket bore a new design. In 1738, it cost 1 guinea 3s.

According to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1830):

The Gardens were originally opened daily (Sundays excepted); and till the year 1792, the admission was 1s; it was then raised to 2s including tea and coffee; in 1809, several improvements were made, lamps added, &c the price was raised to 3s 6d and the Gardens were only opened three nights in the week; in 1821 the price was again raised to 4s.7

|

| Vauxhall season ticket by Hogarth (Amphion on dolphin) from London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century by W & AE Wroth (1896) |

Up until 1750, when Westminster Bridge opened, the easiest way to get to Vauxhall for many people was by wherry along the River Thames from Westminster or the City. After 1750, more visitors chose to arrive by coach or sedan chair or even on foot, but most still travelled by boat. After the opening of Vauxhall Bridge in 1816, most visitors came by road.

In Evelina, published in 1778, the party argued about how to travel to Vauxhall:

Some were for a boat, others for a coach, and Mr. Branghton himself was for walking; but the boat at length was decided upon. Indeed this was the only part of the expedition that was agreeable to me; for the Thames was delightfully pleasant.8

In The Expedition of Humprhy Clinker, Lydia Melford records her experience of travelling to Vauxhall:

At nine o’clock, in a charming moonlight evening, we embarked at Ranelagh for Vauxhall, in a wherry so light and slender that we looked like so many fairies sailing in a nutshell. My uncle, being apprehensive of catching cold upon the water, went round in the coach, and my aunt would have accompanied him, but he would not suffer me to go by water if she went by land; and therefore she favoured us with her company, as she perceived I had a curiosity to make this agreeable voyage—After all, the vessel was sufficiently loaded; for, besides the waterman, there was my brother Jery, and a friend of his, one Mr Barton, a country gentleman, of a good fortune, who had dined at our house—The pleasure of this little excursion was, however, damped, by my being sadly frighted at our landing; where there was a terrible confusion of wherries and a crowd of people bawling, and swearing, and quarrelling, nay, a parcel of ugly-looking fellows came running into the water, and laid hold of our boat with great violence, to pull it ashore; nor would they quit their hold till my brother struck one of them over the head with his cane.9

What were the gardens like?

|

| Vauxhall Gardens from an engraving dated 1751 from South London by W Besant (1899) |

The Picture of London for 1810 described the gardens:

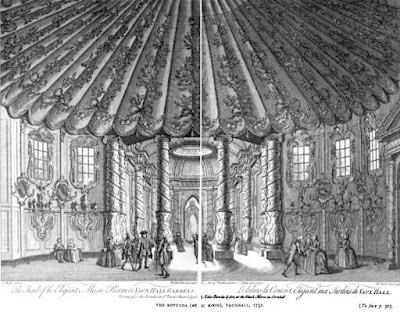

These gardens are beautiful and extensive, and contain a variety of walks, brilliantly illuminated with variegated coloured lamps, terminated with transparent paintings, and disposed with so much taste, that they produce an enchanting effect on first entering the garden. Facing the west door is a large and superb orchestra, decorated with a profusion of lights of various colours. The whole edifice is of wood, painted white and bloom colour. The ornaments are plaistic, a com position something like plaister of Paris, but only known to the ingenious architect who designed and built this beautiful object of admiration. In fine weather the musical entertainments are performed here by a select band of the best vocal and instrumental performers. At the upper extremity of this orchestra, a very fine organ is erected, and at the foot of it are the seats and desks for the musicians, placed in a semi circular form, leaving a vacancy at the front for vocal performers.

Fronting the orchestra is a large pavilion of the composite order, which particularly attracts the eye by its size, beauty, and ornaments. It was built for his late royal highness Frederic Prince of Wales ... In cold or rainy weather, on account of sheltering the company, the musical performers is in a great room, or rotunda, which is seventy feet in diameter, and contains an elegant orchestra. The roof of this rotunda is so contrived, that sounds never vibrate under it; and thus music is heard to the greatest advantage.10

|

| The Rotunda at Vauxhall 1752 from London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century by W & AE Wroth (1896) |

Vauxhall was famous for creating a fairytale-like atmosphere by the huge number of lights, and for the dramatic effect produced when these lamps were lit at dusk. In 1741, there were 1,000 lamps and these could be lit, using a system of linked fuses, in about two minutes. Apparently, the train of oil from whale or seal blubber gave the gardens a distinctive smell! By the end of the 1770s, this number had more than doubled, and by 1822, there were in excess of 20,000 lamps.

There were globe lamps on trees and lamp posts and from the ceilings of supper boxes, with smaller lamps attached to arches and obelisks. Originally these lamps were uncoloured, but coloured (mostly blue) lamps were introduced from 1786, and lamps of all colours were used from around 1806.

The Picture of London for 1810 wrote:

The grove is beautifully illuminated in the evening with about fifteen thousand glass lamps, which glitter among the trees, and produce a brilliant effect.11

The Microcosm of London (1808-10) thought there were rather more lamps:

Vauxhall is a very fascinating place of amusement; but its principal feature is the illumination. Thirty-seven thousand lamps, of various colours, sometimes lighted in these gardens, in the most tasteful forms and brilliant devices, with their associated transparencies, produce a splendour of decoration, unrivalled in any place of amusement in Europe. It is a curious circumstance, and proves the extraordinary change in our manners and habits, that, in a description of these gardens in 1760, the illumination at that time, proceeding only from fifteen hundred comparatively dim lamps, of the same kind, but of a smaller size, as those which now light our streets, is mentioned in as glowing terms as would suit the present extraordinary and accumulated brilliance of the gardens.12

Supper in Vauxhall Gardens

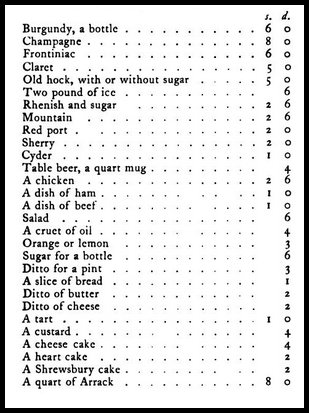

Colonnades of supper-boxes were first introduced in 1736 and these became an ongoing feature of the gardens. Below is a bill of fare for 1762. According to Coke and Borg, the waiters had to pay for food when they collected the orders from the kitchens, so they bore the risk of customers refusing to pay. The gardens were notorious for the thinness of the slices of ham and for the alcoholic beverage arrack or arrack punch that was served.

|

| A bill of fare for Vauxhall for 1762 from London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century by W & AE Wroth (1896) |

The Picture of London for 1810 wrote:

Passing from the intellectual attractions of this fashionable place of resort, to the more solid allurements of sense and appetite, we must observe that the best kind of refreshments is provided with the utmost attention, and charged according to a reasonable bill of fare, with the prices annexed.13

In Vanity Fair, Thackeray wrote:

The two couples were perfectly happy then in their box: where the most delightful and intimate conversation took place. Jos was in his glory, ordering about the waiters with great majesty. He made the salad; and uncorked the Champagne; and carved the chickens; and ate and drank the greater part of the refreshments on the tables. Finally, he insisted upon having a bowl of rack punch; everybody had rack punch at Vauxhall. ‘Waiter, rack punch.’14

The arts at Vauxhall

Vauxhall had strong links with several renowned artists of its day. The supper boxes and other buildings were decorated with paintings by a variety of artists including Francis Hayman and William Hogarth. The gardens displayed the sculpture of Louis François Roubiliac, notably that of George Frideric Handel, whose music was frequently played in the gardens.

The Picture of London for 1810 wrote:

The different boxes and apartments of these gardens are adorned with a vast number of paintings, many of which are executed in the best style of their respective theatres. The labours of Hogarth and Hayman are the most conspicuous. Hayman has chosen his subjects from the works of Shakespeare; but as the pictures are too numerous to be particularized, we leave them and their merits for the inspection of the curious.15

According to The Microcosm of London:

The grove, principal entrance, and other parts of the gardens, are furnished with a great number of small pavilions, ornamented with paintings, chiefly by Hogarth and Hayman; each containing a table and seats, to which the company retire, at the conclusion of the concert, to enjoy the refreshments prepared for them. Some of these pavilions are very elegant. That which is opposite the orchestra, and is called the Prince's pavilion, having been erected for the accommodation of Frederic, Prince of Wales, his present Majesty's father, is a very beautiful example of Palladian architecture. During the remainder of the evening, bands of wind-instruments, of different kinds, are placed in different parts of the gardens, which contribute to enliven the scene and invite the dance.16

The statue of Handel was moved around the gardens somewhat over the years. According to The Picture of London for 1810:

In the middle of the piazza is a grand portico of the Doric order, and under the arch, on a pedestal, is a beautiful marble statue of Handel, in the character of Orpheus, playing on his lyre, done by the celebrated Mr Roubiliac.17

However, The Microcosm of London (1808-10) recorded:

At the end of this [supper] room was the statue of the immortal Handel, in white marble, and in the character of Orpheus singing to his lyre; but is now removed behind the orchestra in the garden. This fine specimen of sculpture first introduced the abilities of Roubiliac to the notice of the public. It was begun and completed in the place of which it is the ornament, while the noble subject and the superior artist were enjoying the friendly and protecting hospitality of Mr Jonathan Tyers. It is said to bear a strong resemblance to the great musician.18

Entertainment at Vauxhall

The main entertainment at Vauxhall was promenading in the gardens and listening to music, from the Orchestra or in the Rotunda or one of the other buildings.

Firework shows were very popular and featured at Vauxhall from 1798. The gardens sought to rival the excitement of Astley’s with acrobats and tightrope walkers, including the famous Madame Saqui who performed at Vauxhall from 1816 to 1820.

Other entertainments included mechanical attractions such as the Cascade which operated for about fifteen minutes during the evening for many years. You can read more about the Cascade at Vauxhall here.

Special events included balloon ascensions and masquerades and displays celebrating, for example, the Battle of Waterloo.

|

| Vaux-Hall by Thomas Rowlandson (1785) © British Museum 1880,1113.5484 (22) |

A description of the gardens from Evelina

In Fanny Burney’s novel of the same name, Evelina describes the gardens:

The garden is very pretty, but too formal; I should have been better pleased, had it consisted less of straight walks, where 'Grove nods at grove, each alley has its brother'.The trees, the numerous lights, and the company in the circle round the orchestra make a most brilliant and gay appearance; and had I been with a party less disagreeable to me, I should have thought it a place formed for animation and pleasure. There was a concert; in the course of which a hautbois concerto was so charmingly played, that I could have thought myself upon enchanted ground, had I had spirits more gentle to associate with. The hautbois in the open air is heavenly.19

A description of the gardens in 1811

In a letter by Samuel Morse written in 1811, he described Vauxhall Gardens:

A few evenings since I visited the celebrated Vauxhall Gardens, of which you have doubtless often heard. I must say they far exceeded my expectations; I never before had an idea of such splendor. The moment I went in I was almost struck blind with the blaze of light proceeding from thousands of lamps and those of every color.In the midst of the gardens stands the orchestra box in the form of a large temple and most beautifully illuminated. In this the principal band of music is placed. At a little distance is another smaller temple in which is placed the Turkish band. On one side of the gardens you enter two splendid saloons illuminated in the same brilliant manner. In one of them the Pandean band is placed, and in the other the Scotch band. All around the gardens is a walk with a covered top, but opening on the sides under curtains in festoons, and these form the most splendid illuminated part of the whole gardens. The amusements of the evening are music, waterworks, fireworks, and dancing.20

|

| The Orchestra at Vauxhall from London Pleasure Gardens of the 18th Century by W & AE Wroth (1896) |

Jonathan Tyers owned the gardens until his death in 1767, after which the gardens were managed by his wife Elizabeth, then by his son, Jonathan Tyers the younger, and then from 1786-1809, by the younger Jonathan’s son-in-law, Bryant Barrett. After this, the gardens passed to Bryant’s sons, George and Jonathan Tyers Barrett.

According to The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1830):

In 1818, the entire property was advertised for sale, but no purchaser was obtained. In 1821 it was purchased by the London Wine Company; and it is but bare justice to say they have done all in their power to revive the fashionable celebrity of Vaux-hall. Had not a purchaser been found at the last-mentioned date, the fairy groves and palaces would have fallen before the mere speculator, and the site would be now covered with houses— for the whole was, in the language of the roadside, ‘to be let as building ground.’21

The gardens were not, in fact, bought by the London Wine Company in 1821, but leased by its owner, Frederick Gye, and his business partner Thomas Bish. Under their management, the gardens gained the accolade of The Royal Gardens, Vauxhall. Gye went on to buy the gardens from the Barrett family with Richard Hughes in 1825. The gardens were sold to Thomas Fowler, Bish’s son-in-law, in 1841, and he leased the gardens to a variety of people during the 1840s and 1850s. Ultimately, the gardens failed to develop in such a way as to appeal to the Victorian public and opened for the last time on Monday 25 July 1859.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Smollett, Tobias, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771).2. Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

3. Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

4. Burney, Fanny, Evelina or the history of a young lady’s entrance into the world (1778).

5. Feltham iop cit.

6. Ackermann op cit.

7. The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1830).

8. Burney op cit.

9. Smollett op cit.

10. Feltham op cit.

11. Ibid.

12. Ackermann op cit.

13. Feltham op cit.

14. Thackeray, William Makepeace, Vanity Fair (1848).

15. Feltham op cit.

16. Ackermann op cit.

17. Feltham op cit.

18. Ackermann op cit.

19. Burney op cit.

20. Morse, Samuel FB, Samuel Morse, His letters and journals, edited and supplemented by his son Edward Lind Morse (1914).

21. The Mirror op cit.

22. Used under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International license.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Besant, Walter, South London (1899)

Burney, Fanny, Cecilia or Memoirs of an Heiress (1782)

Burney, Fanny, Evelina or the history of a young lady’s entrance into the world (1778)

Coke, David and Borg, Alan, Vauxhall Gardens, a history (2011)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Hassan Khan, Mirza Abul, A Persian at the Court of King George 1809-10, edited by Margaret Morris Cloake (1988)

Morse, Samuel FB, Samuel Morse, His letters and journals, edited and supplemented by his son Edward Lind Morse (1914)

Smollett, Tobias, The Expedition of Humphry Clinker (1771)

Thackeray, William Makepeace, Vanity Fair (1848)

The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1830)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1878, London) Vol 6

Walpole, Horace, Horace Walpole and his World, Select passages from his letters ed LBSeeley (1884)

Wroth, Warwick and Wroth, Arthur Edgar, The London Pleasure Gardens of the eighteenth century (1896)

Vauxhall Gardens website

Vauxhall and Kennington website