|

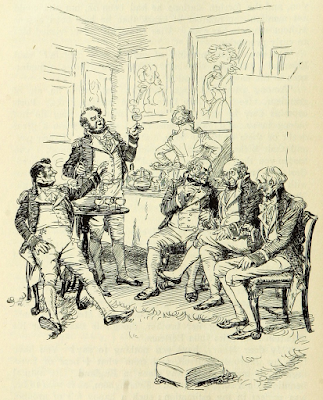

| The Dashwoods at dinner with the Middletons Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (1811) Illustration by Hugh Thomson (1896) |

This post looks at the question of drink at the dinner table and afterward – what they drank, the customs of taking wine and drinking healths, and when ladies withdrew to leave gentlemen at their wine.

What did they drink?

In Domestic Duties (1825), Mrs Parkes wrote about the drinks to serve at a dinner party:

The wines are placed upon the table at first, in six decanters, one of each being placed at each corner of the table, and one on each side of the epergne, whilst two bottles of some light French or Rhenish wine, undecanted and corked, and placed in silver or plated vases, fill up a space between the epergne and each end of the table. Small decanters of water, covered with an inverted tumbler, should be placed by every second guest, but malt liquors, cider, soda-water, ginger-beer, or similar beverages, are handed by the attendants when called for. In the interval of each course, champaign, hock, burgundy, or barsac, are handed round to each guest. Cheese, with a fresh salad, follows the third course, and a glass of port wine is generally offered by the servants to each of the gentlemen.

She continued:

The decanted wines placed on the table during dinner are white wines; either madeira, sherry, or buçellus; those circulated after dinner are port, madeira, and claret. Claret is generally contained in a decanter with a handle, and of a peculiar form.1

According to Simond, a French visitor to England, writing in 1810:

The wine generally drank is Port, high in colour, rough, and strong,— Madeira, and Sherry; Bourdeaux wine, usually called here Claret, Burgundy, Champagne, and other French wines, are luxuries; few of these wines come to England without some heightening of brandy. People generally taste of fewer dishes here than at Paris, each dining generally on one or two. You are not pressed to eat or drink. The ordinary beverage during the dinner is small-beer, porter rarely, and sparkling ale, which is served in high shaped glasses like Champagne glasses; water, acidulated by the carbonic gas, is frequently used: few drink wine and water mixed. The crystal vessels, called decanters, in which wine is brought on table, are remarkably beautiful.3

In A System of Etiquette (1804), Trusler gave advice to young gentlemen starting out in society:

Call for any wine you please, without waiting to be asked; in some houses, the master announces to his company, the different sorts of wine on the side board; in great houses, where this is not done, all common wines are supposed to be present. At the house of a friend, you are expected to be as much at your ease, as if at home, and of course may freely ask for any wine, you know the master is accustomed to keep, whether it is on the side-board or not, and whether before dinner or after. But this liberty is seldom taken by those, who do not give the same liberty at their own houses.3

|

| The dining room, Calke Abbey |

I must admit that I have found the references to taking wine with another person and drinking healths at the dinner table quite confusing. It has taken me a while to realise that these are two separate things.

Taking wine at the table

The custom of taking wine with another person at the table appears to have been a polite way to ensure the ladies had sufficient to drink without them having to ask. It was also a way of paying a compliment to another lady or gentleman.

In The Honours of the Table (1791), Trusler wrote:

As it is unseemly in ladies to call for wine, the gentleman present should ask them in turn, whether it is agreeable to drink a glass of wine. (“Mrs. ---- , will you do me the honour to drink a glass of wine with me?”) and what kind of the wine present they prefer, and call for two glasses off such wine, accordingly. Each then waits till the other is served, when they bow to each other and drink.4

Although this guide was written some years before the Regency, Jane Austen’s nephew, James Edward Austen-Leigh (1798–1874) remembered the custom from his youth. In his Memoir of Jane Austen (1871), he wrote:

Who can now record the degrees by which the custom prevalent in my youth of asking each other to take wine together at dinner became obsolete?5

The custom of taking wine was still practised when Arthur Freeling wrote The Pocket Book of Etiquette (1837):

You must not ask a lady to take wine until she has finished her soup or fish. If you are seated near the hostess, it will be a mark of respect to ask her to take wine with you, before requesting the honor of any other lady: the lady who has accompanied you to the table next demands your attention. If either lady or gentleman be asked to take wine, they must not refuse; it is only necessary to taste, if more than this be unpleasant.6

In Domestic Duties (1825), Mrs Parkes wrote:

Mrs L - Can a lady refuse to take wine with a gentleman when requested ?

Mrs B - It is not the custom to refuse the request, nor is it considered polite; though I think it may be done, provided the manner in which it is done, be so tempered by politeness as to avoid the unpleasantness of offending.7

In Maria Edgeworth’s Belinda (1801), Mr Hervey invites a lady to take wine with him:

He was nearly struck dumb by the forbidding severity with which an elderly lady, who sat opposite to him, fixed her eyes upon him…He asked her to do him the honour to drink a glass of wine with him. She declined doing him that honour; observing that she never drank more than one glass of wine at dinner, and that she had just taken one with Mr Percival.8

|

| Drinking to Isabella Thorpe Northanger Abbey by Jane Austen (1817) Illustration by Hugh Thomson (1897) |

The drinking of healths was a more complicated ritual. Writing in 1810, Simonds explained the custom:

It was done in this way: One of the guests challenged another, male or female; this being accepted by a slight inclination of the head, they filled respectively, each watching the motions of his adversary, then raised their glasses, bowing to each other, and in this attitude, looking round the table, they had to name every one of the company successively; this ceremony finished, the two champions eyed each other gravely, and carrying their glasses to their lips, quaffed their wine simultaneously. As one challenger did not wait for another, and each guest matched himself without minding his neighbours, the consequence was, circular glances, calls of names, and mutual bows, forming a running-fire round the table, crossing in every direction. It was then the invariable custom to introduce guests to each other by name, and it was quite necessary to recollect these names, in order to drink their healths at table. This custom of introducing is losing ground every day.9

Did they drink healths in the Regency?

Trusler wrote in 1791:

Drinking of healths is now growing out of fashion, and is very unpolite in good company. Custom once had made it universal, but the improved manners of the age, now render it vulgar. What can be more rude or ridiculous, than to interrupt persons at their meals, with unnecessary compliments? Abstain then from this silly custom, where you find it out of use, and use it only at those tables, where it continues general.10

In 1804, Trusler wrote that this practice had gone out of fashion completely:

Drinking of healths during dinner or supper, among the first class of people, is entirely exploded; but if the master of the house sets the example, you may follow it.11

Simonds does not quite agree with this. Writing in 1810, he said:

Formerly it was the invariable custom to drink every body's health round the table; and although less general now, it is by no means entirely abolished.12

Mrs Parkes had a different opinion. Writing of the custom of drinking healths, she said:

I think the total omission of the old custom not altogether defensible; for, although the routine of drinking healths by every individual is a formality which may be well dispensed with, yet I should prefer the ancient fashion to be preserved, as far as regards the friends at whose social board we are guests, and whose attentions seem to claim some acknowledgement and tribute of respect on our parts. There is in my mind an apparent heartlessness in the present fashion; and a little of that honest warmth which characterized the rude hospitality of our forefathers would not detract from the refinement of the present age, but would increase the pleasures of the social table.13

|

| A circle of admirals Mansfield Park by Jane Austen (1814) Illustration by Hugh Thomson (1897) |

Trusler wrote in The Honours of the Table (1791):

Habit having made a pint of wine after dinner almost necessary to a man who eats freely, which is not the case with women, and as their sitting and drinking with the men, would be unseemly; it is customary after the cloth and desert [sic] are removed and two or three glasses of wine are gone round for the ladies to retire and leave the men to themselves, and for this, ’tis the part of the mistress of the house to make the motion for retiring, by privately consulting the ladies present whether they please to withdraw. The ladies thus rising, the men should rise of course, and the gentlemen next the door should open it, to let them pass.14

Simonds observed in 1810:

Soon after dinner the ladies retire, the mistress of the house rising first, while the men remain standing. Left alone, they resume their seats, evidently more at ease, and the conversation takes a different turn, — less reserved,— and either graver, or more licentious.15

I like the closing instruction from Mrs Parkes in this excerpt from Domestic Duties (1825) on the ladies leaving the gentlemen to their wine, that the coffee should be served early, and the gentlemen summoned!

The custom for the ladies to retire soon after dinner is the relic of a barbarous age, when the bottle circulated so freely, and toast upon toast succeeded each other so rapidly, that the gentlemen of a company soon became unfit to conduct themselves with the decorum essential in the presence of the female sex. But in the present age, when temperance is a striking feature in the character of a gentleman; and when delicacy of conduct towards the female sex has increased with the esteem in which they are now held, on account of their superior education and attainments, the early withdrawing of the ladies from the dining room is to be deprecated; as it prevents much conversation which might afford gratification and amusement, both to the ladies and the gentlemen. The truth of this remark is almost generally acknowledged in polite circles; and it is not, now, customary for the ladies to retire very soon after dinner. A lapse in the conversation will occasionally indicate a seasonable time for the change to take place.

I may take this opportunity of remarking, that servants should be instructed to attend to the drawing-room fire, and to prepare the lights after dinner. Prints, periodical works, or other publications of a light kind, ought to be dispersed about the room, and are sometimes useful to engage the attention, when any thing like ennui is observable.

Coffee should be brought up soon, and the gentlemen summoned.16

|

| The gentlemen join the ladies after dinner Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813) Illustration by C E Brock (1895) |

It depends! The length of time that the gentlemen were left to drink depended on personal preference. If Mrs Parkes’s instructions above were followed, not long.

Espriella, writing in 1802 wrote:

They take less wine than we do at dinner, and more after it; but the custom of sitting for hours over the bottle, which was so prevalent of late years, has been gradually laid aside, as much from the gradual progress of the taxes as of good sense.17

In Jane Austen's Emma, Emma’s father does not sit long over his wine:

Mr Woodhouse very soon followed them into the drawing-room. To be sitting long after dinner, was a confinement that he could not endure. Neither wine nor conversation was any thing to him; and gladly did he move to those with whom he was always comfortable.18

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes- Parkes, Mrs William, Domestic Duties or Instructions to young married ladies on the management of their households (London, 1825).

- Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 (1815).

- Trusler, Rev Dr John, A System of Etiquette (1804).

- Trusler, John, The Honours of the Table, or, rules for behaviour during meals (1791).

- Austen-Leigh, James Edward, Memoir of Jane Austen (1871).

- Freeling, Arthur, The Pocket Book of Etiquette (Liverpool, 1837).

- Parkes op cit.

- Edgeworth, Maria, Belinda (1801).

- Simond op cit.

- Trusler, John, The Honours of the Table, or, rules for behaviour during meals (1791).

- Trusler, Rev Dr John, A System of Etiquette (1804).

- Simonds op cit.

- Parkes op cit.

- Trusler, John, The Honours of the Table, or, rules for behaviour during meals (1791).

- Simonds op cit.

- Parkes op cit.

- Espriella, Don Manuel Alvare, Letters from England, translated from the Spanish by Robert Southey 3rd edition (1814) Volume 1.

- Austen, Jane, Emma (1815).

Austen, Jane, Jane Austen's Letters, Collected and Edited by Le Faye, Deirdre (Oxford University Press, 1995)

Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814)

Austen, Jane, Northanger Abbey (1817)

Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

Austen, Jane, Sense and Sensibility (1811)

Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892)

Austen-Leigh, James Edward, Memoir of Jane Austen (1871)

Cruickshank, Dan and Burton, Neil, Life in the Georgian City (1990)

Edgeworth, Maria, Belinda (1801)

Espriella, Don Manuel Alvare, Letters from England, translated from the Spanish by Robert Southey 3rd edition (1814) Volume 1

Freeling, Arthur, The Pocket Book of Etiquette (Liverpool, 1837)

Parkes, Mrs William, Domestic Duties or Instructions to young married ladies on the management of their households (London, 1825)

Trusler, Rev Dr John, A System of Etiquette (1804)

Trusler, John, The Honours of the Table, or, rules for behaviour during meals (1791)

Most interesting! Thank you, especially for your excellent list of sources.

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you found it useful.

Delete