|

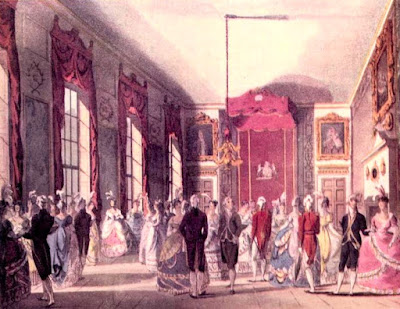

| A drawing room at St James's Palace from The Microcosm of London by R Ackermann and W Combe (1808-10) |

Just after two o’clock, the centre door was thrown open and Her Majesty Queen Charlotte entered, followed by the princesses and a whole bevy of servants. Although the Queen looked magnificent in dark green velvet and gold embroidery, Castleford could not help thinking, with an inner chuckle, that the Duchess of Wessex looked more regal.1

Was it just young ladies who were presented?

A common misconception is that only young ladies coming out into society for the first time were presented to the Queen. Both men and women were presented at court, at different times, for different reasons.

Lamb wrote in A book explaining the ranks and dignities of British Society (1809):

People are presented on different occasions: on first coming into the world, (which young ladies usually do about seventeen or eighteen); on their marriage, or any change of name; on going abroad, or to Ireland; or to an appointment to any situation about their majesties or the royal family.

Gentlemen are also presented on obtaining a commission in the army; promotion in the army or navy; a place under government; or any high situation in the church or law.2

A newspaper report of the Queen’s Drawing room held on 8 March 1810 stated:

Yesterday her Majesty held a Drawing-room, at which the following were presented:

Lady George Beresford, by the Countess of Arran.

Miss Harriet Thornton, by her mother, Mrs S Thornton.

Lady Charlotte Graham, by her mother, the Duchess of Montrose.

Mr Roust Broughton, on his coming of age, by his father.

Lady Mary Sackville, by her mother, the Duchess of Dorset.

The two Misses Wellesley Pole, by their mother, Mrs W Pole.

Mr Villiers, upon his return from Portugal.

Mr Yorke, upon his being appointed a Teller of the Exchequer.

Major-General Sir Stapleton Cotton, on his return from Portugal, and on coming to his title.3

Presentation of gentlemen

|

| George III from The Public & Domestic Life of his late, most gracious majesty by E Holt (1820) |

Gentlemen are all presented first to his majesty at the levee, and to her majesty at the following drawing room: they are generally presented by their nearest relation, who gives a card with their name, and the occasion of their being presented written upon it, to the lord of the bed-chamber in waiting. He names them to the king when they get up to him in the circle, on which they kneel down on one knee and kiss his hand.

To her majesty, the ceremony for gentlemen is the same, only that the card is given to her lord chamberlain.4

Presentation of ladies

Lamb wrote:

Ladies were presented to the king at the same drawing-room, but before they were presented to her majesty; but since the king has gone so much seldomer to court, they have been presented first to the queen at a common drawing-room, and to the king at the birth-day following; and those invited by her majesty to the entertainments at Windsor, have been presented to his majesty there: in that case, they are not in court dresses, but the ceremony is the same. On their being named to the king, by the lord of the bed-chamber, they make a low courtesy, and he salutes them; but their right-hand glove should be off, as if they intended to take his hand to kiss.

To her majesty, the ceremony of presentation for ladies is different according to their rank: all under the rank of right honourable kiss the queen’s hand, making so low a courtesy as to have almost the appearance of kneeling; she salutes those who have that rank, though they equally have their glove off.5

What did gentlemen wear to court?

|

| Gentleman in court dress from A book explaining the ranks and dignities of British Society by C Lamb (1809) |

The court dress for gentlemen is what is commonly called a full dressed coat, without collar or lappels, made of silk, velvet, or cloth, and often richly embroidered in gold, silver, or coloured silks. Any naval or military uniform is reckoned a full dress, though many regimentals have, properly speaking, no full dressed uniform; those that have, cannot appear at court in the undressed uniform.

People are allowed to go to court in private mourning, except on the birth-days. Their uniforms, with a piece of black crape tied round the arm, are reckoned sufficient for officers in the deepest mourning.

Gentlemen not in uniform, wear what are called weepers in deep mourning, which are merely cambric cuffs, with broad hems turned back upon the sleeves.6

What did ladies wear to court?

|

| Lady in court dress from A book explaining the ranks and dignities of British Society by C Lamb (1809) |

The court-dress for ladies is now distinguished only by the hoop, lappets, and full ruffles; for the mantua is now made exactly like any other open gown, and differently in shape before, according to the fashion of the year: the petticoat also is plain or trimmed, according to the fancy of the wearer. The most general form is the one followed in the plate; of late, it has been more the fashion to have the petticoat, both the drapery and the under part, of the same colour as the gown; but a coloured drapery over a white petticoat prevailed for many years, and the drapery was even often of a different colour from the gown. Velvet, sattin, silk, crape, and gause, are the only materials allowed for ladies’ court dresses; the lappets are sometimes of black lace, but oftener the same as the ruffles of fine lace or blonde. Court dresses are trimmed, and often embroidered with gold and silver; and artificial flowers are much used in ornamenting the petticoat. Feathers are not reckoned a necessary part of a court dress; but young ladies very seldom go without them, and they are supposed to be under dressed if they do.

In deep mourning, ladies wear a black hood, put on as it is represented in the plate.

Court mournings are worn by every body, according to the degree of relationship in which the person mourned for stood to his majesty.7

La Belle Assemblée recorded the dresses worn by two young ladies being presented at the Queen’s birthday drawing room in January 1810:

Two Miss Ruffos – Presented by their mother, the Princess Castelcicala, wore white crape dresses, elegantly trimmed with white satin ribbon and bunches of pink roses; robes, white satin, trimmed to correspond with the dresses.8

Lots of others are described in the same report. I thought the Duchess Dowager of Leeds’s outfit sounded particularly impressive:

A superb petticoat of white crape richly embroidered in real silver, with a border embroidered on crimson velvet, in a style perfectly unique, and beautiful, draperies richly embroidered and tastefully festooned with bunches of silver laurel and brilliant tassels; body and train of crimson velvet trimmed with silver point; head-dress, Caledonian cap of crimson velvet, diamonds, and ostrich feathers.9

What happens at a drawing room?

|

| Queen Charlotte from The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel Wraxall (1884) |

At the entrance of the drawing-room, the page resigns the queen’s train to the lady of the bed-chamber, who hangs it over her arm, and keeps it there during the whole of the drawing-room; of course, she must then follow before the princesses.

The queen courteseys to the king on entering the drawing room, which she then goes round to the left, while he is doing so to the right; and their majesties speak to every person as they get up to them. The page, gentleman usher, and bed-chamber women, do not follow the queen into the inner drawing-room, nor the ladies of the bed-chamber not in waiting; and the maids of honour do not go round it with her, but stand altogether at one end till the drawing-room is over, when they follow her out, and fall into the train in their places in the outward drawing-room. Their majesties come and go through the levee-rooms.

Since there have been drawing-rooms so much seldomer, (only on every other Thursday) and that, of course, they have been more crouded, their majesties, instead of going round the room, have stood each with their back to a table between the windows, and the company have gone up to them. Any of the royal family coming to court, go in at the middle door, the company at one of the two side doors; and since their majesties have stood still, they should go in at the door next the windows, and out at the other.10

This seems to agree with the account of the Queen’s birthday drawing room on Thursday 18 January 1810 as reported in the Gentleman’s Magazine:

This day being appointed for keeping the birthday of her Majesty, soon after nine, their Majesties, the Princesses, the Dukes of York, Clarence, Kent, Cumberland, Cambridge, Sussex, and Gloucester, and Princess Charlotte of Wales, breakfasted together at the Queen's Palace. At half past twelve, her Majesty, attended by the Princesses, proceeded to the Duke of Cumberland’s apartments in St James's Palace, to dress. The Royal Party then proceeded to the Grand Council Chamber, conducted by the Earl of Morton and Col Desbrow. Her Majesty’s approach being announced, the centre door was thrown open; her Majesty entered about ten minutes past two o’clock, and took her station between the second and third window, leaning against a marble slab table. Her Majesty, as usual, it being the celebration of her own birthday, was dressed very plain. The Princesses arranged themselves on her Majesty's left hand, according to their ages. Their attendants stood nearly under the throne. The Royal Dukes stood near their Royal Sisters—Her Majesty having taken her station to receive the congratulations of the company and the presentations, the Lord Chamberlain waved his wand to Sir W Parsons, who was attending in an anti-room behind the throne, with his Majesty's band, to perform the Ode for the New Year. The presentations were very numerous; and the illuminations in the evening very general.11

How to conduct yourself in the presence of royalty

Fanny Burney recorded in her diary:

Not even the Princesses, ever speak in the presence of the King and Queen, but to answer what is immediately said by themselves. There are, indeed, occasions in which this is set aside, from particular encouragement given at the moment; but it is not less a rule, and it is one very rarely infringed.12

However, Fanny’s friend, Mrs Delany told her:

When the queen or the king speak to you, not to answer with mere monosyllables. The queen often complains to me of the difficulty with which she can get any conversation as she not only always has to start the subjects, but, commonly, entirely to support them: and she says there is nothing she so much loves as conversation, and nothing she finds so hard to get.13

No coughing, sneezing or fidgeting whilst in the presence of their Majesties was allowed. Fanny wrote:

In the first place, you must not cough. If you find a cough tickling in your throat you must arrest it from making any sound; if you find yourself choking with the forbearance, you must choke – but not cough.

In the second place, you must not sneeze. If you have a vehement cold, you must take no notice of it; if your nose membranes feel a great irritation, you must hold your breath; if a sneeze still insists upon making its way, you must oppose it, by keeping your teeth grinding together; if the violence of the repulse breaks some blood-vessel, you must break the blood-vessel – but not sneeze.

In the third place, you must not, upon any account, stir either hand or foot. If, by chance, a black pin runs into your head, you must not take it out. If the pain is very great, you must be sure to bear it without wincing; if it brings the tears into your eyes, you must not wipe them off; if they give you a tingling by running down your cheeks, you must look as if nothing was the matter.14

Public viewing

Apparently, it was possible to watch the drawing room from a viewing gallery:

There are three rooms in which those desirous of seeing the company go to court may stand, by obtaining tickets from the lord chamberlain: the guard-chamber, the royal presence-chamber, and the privy-chamber; in the last only, they also see the king, queen, and royal family pass, as it is between the levee-rooms and the outer drawing-room.15

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

- Rachel Knowles, A Reason for Romance (2021).

- Lamb, Charles, A book explaining the ranks and dignities of British Society (1809).

- The Times online archive, 9 March 1810.

- Lamb op cit.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- La Belle Assemblée (January 1810).

- Ibid.

- Lamb op cit.

- Gentleman’s Magazine (January 1810).

- Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett Volume III (1842).

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Lamb op cit.

Sources used include:

Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett Volume III (1842)

Gentleman’s Magazine (1810) Lamb, Charles, A book explaining the ranks and dignities of British Society (1809)

La Belle Assemblée (January 1810)

The Times online archive

What was the difference between these drawing room presentations and Queen Charlotte's ball? I was under the impression that Queen Charlotte's ball was where debutatnes were first introduced to the Queen.

ReplyDeleteLadies were presented to the Queen at drawing rooms as I've described above. These were often mentioned in the newspapers and magazines. These were court affairs with lots of standing around whereas a ball would involve dancing. I guess ladies might be re-introduced to the Queen at such an event, but this would not have been their presentation. I don't think ladies could dance in their court dresses!

DeleteWhat was the order in which the young ladies were presented? I read somewhere that it’s in order of rank, but is it ascending or descending order? Great write-up, btw. Very informative.

ReplyDeleteStill working on this. The reports of presentations that I've looked at so far don't seem to suggest any particular order.

Delete