|

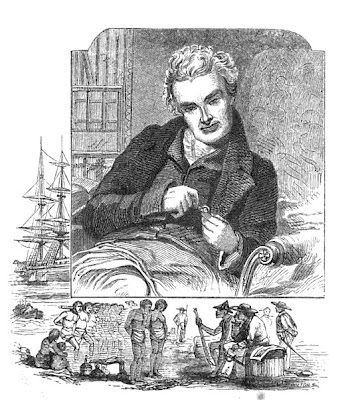

| William Wilberforce from The Great and Good (1855) |

Wilberforce’s political career started in September 1780 when he was elected MP for Hull at the age of twenty-one, having spent £8000 ‘buying’ supporters at the going rate of two guineas a vote, as was the custom at the time. Four years later, he was elected one of the MPs representing the County of York, a prestigious but demanding role from which he resigned in 1812 due to ill health. He then became an MP for the pocket borough of Bramber in Sussex. This enabled him to stay in the Commons but was less taxing on his health and allowed him to spend more time with his family.

The independent politician

Wilberforce’s private resources allowed him to be independent of any political party as he did not need to seek a paying public office. He was a passionate speaker and was able to captivate the house whenever he spoke. His earliest recorded speeches were on smuggling and naval shipbuilding – things close to the heart of his Hull constituents – but it was not until he took up the anti-slavery cause that his political contribution became significant.

The abolitionist cause

After his conversion to evangelical Christianity, Sir Charles and Lady Middleton and Thomas Clarkson urged Wilberforce to take up the plight of slaves in Parliament. After a pivotal discussion with William Grenville and William Pitt the Younger under an oak tree at Holwood in Kent – later known as the “Wilberforce oak” – Wilberforce became fully committed to the cause and thereafter sought the abolition of the slave trade.

Wilberforce launched his campaign for the abolition of slavery on 12 May 1789 and continually brought the matter before Parliament despite repeated disappointment and opposition. In 1791, he helped his friend, Henry Thornton, to establish the Sierra Leone Company to resettle former slaves and promote legitimate trade and on 31 January 1807, his book, A Letter on the Abolition of the Slave Trade, was published. Finally, Wilberforce’s perseverance was rewarded and the Abolition of the Slave Trade Act received royal assent on 25 March 1807.

But Wilberforce’s efforts did not stop there. The Anti-Slavery society was created in 1823 and, for the rest of his life, he worked towards the total abolition of slavery.

The Clapham Sect

During the 1790s and 1800s, Wilberforce was a leading member of the group of evangelical Christians known as the Clapham Sect, so named because of their location around the green at Clapham. These included Henry Thornton, Edward Eliot, Charles Grant, Zachary Macaulay, John Shore (Lord Teignmouth), and James Stephen (who married Wilberforce’s sister, Sarah, in 1800).

He was informally recognized as the leader of the group of evangelical ‘Saints’ in Parliament and the second great cause in his life was to promote true Christian values – what he called “the reformation of manners”.

With this in mind, Wilberforce successfully urged George III to issue a proclamation for the encouragement of piety and virtue on 1 June 1787 and in April 1797, his work, A practical view of the prevailing religious system of professed Christians in the higher and middle classes of this country contrasted with real Christianity, was published. Although this was unfashionable, it was widely read and influential.

The Queen Caroline Affair

On 6 June 1820, Queen Caroline returned from her exile on the continent, claiming her right to be crowned as Queen, despite the attempts of her adviser, Lord Brougham, to prevent her return to England. The injured Queen became a figurehead for the political unrest that had been made worse by the Peterloo Massacre of 16 August 1819. George IV wanted to put his wife on trial for adultery so that he could divorce her.

Wilberforce feared that in the current state of unrest, such a move could lead to revolution. He proposed that the “Green Bag” debate over the Queen’s alleged adultery be adjourned, giving time for the King and Queen to reach a settlement outside of the courts. The move was enthusiastically taken up and in the process nearly brought the government down.

Wilberforce presented a Motion for an Address to the Queen, and was encouraged by Lord Brougham to believe that the Queen would accept the omission of her name from the liturgy. The Queen refused. The failure of Wilberforce’s attempts at mediation led to the trial of Queen Caroline and subsequent exclusion from the coronation ceremony.

|

| Princess Caroline of Brunswick from Huish's Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta (1818) |

Wilberforce’s legacy

Wilberforce resigned from politics in 1825 due to ill health and died on 29 July 1833, three days after the Abolition of Slavery Bill had passed its third hearing in the House of Commons. It came into force the following year. Wilberforce was honoured by members of both Houses and buried in Westminster Abbey. He will always be remembered for his perseverance in the struggle against slavery.

Read more about the rest of Wilberforce's life

Sources used include:

Cooper, Charles Henry, Memorials of Cambridge (1861, William Metcalfe)

Huish, Robert, Memoirs of George IV (1830, Thomas Kelly)

Pollock, John, Wilberforce (1977, Constable)

Price, Thomas, Memoir of William Wilberforce (1836, Light & Stearns, Boston)

Seeley, Jackson & Halliday, The Great and Good ( 1855, Seeley, Jackson & Halliday)

Vizetelly & Branston, The Georgian Era (1832, Vizetelly, Branston & Co.)

Weale, John, The Pictorial Handbook of London (1854, Henry G Bohn)

Wilberforce, Robert Isaac and Samuel, The Life of William Wilberforce (1839, John Murray)

Great piece. But Wilberforce's campaign in 1789 was for the abolition of the slave trade, not slavery. They were two different issues, though obviously connected. As you go on to note, the campaign to abolish slavery didn't get going until 1823. Anne Stott, author of 'Wilberforce: Family and Friends' (Oxford, 2012)

ReplyDelete