|

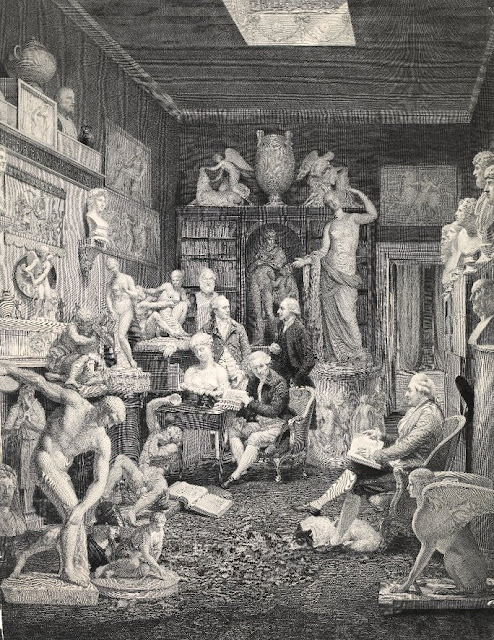

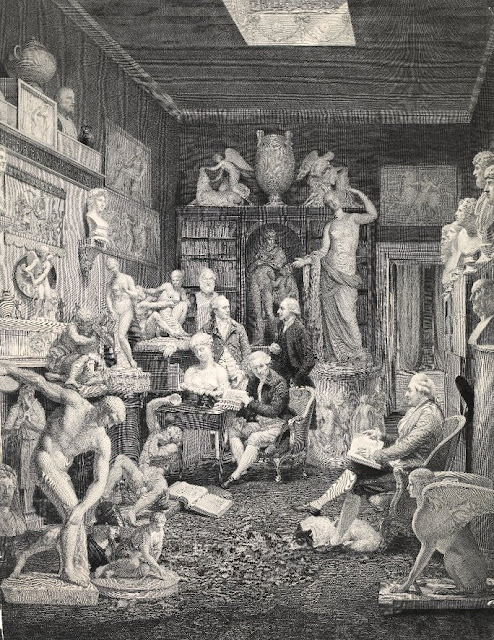

The Towneley Museum

Print by William Henry Worthington after Johan Joseph Zoffany (1833)

Charles Townley is in the chair to the right.

© Trustees of the British Museum |

Profile

Charles Townley (1 October 1737 - 3 January 1805) was an antiquarian and collector and a trustee of the

British Museum.

Early life

Charles Townley was born on 1 October 1737 at Towneley Hall near Burnley in Lancashire, the eldest child of William and Cecilia Towneley1. Because the family was Catholic, there were limited educational opportunities available for Townley in England, and so, in 1747, he and his brother Ralph were sent to be taught at the English College at Douai in northern France.

In 1753, Townley moved to Paris where he was tutored by the Reverend John Turberville Needham before being introduced into Paris society by his father’s uncle, the Chevalier John Towneley.

The country gentleman

In 1758, Townley came of age and took control of the lands that he had inherited from his father back in 1742. He was a good landlord, improving his estates, and enjoying the life of a country gentleman. He was also involved in the construction of the Leeds-Liverpool canal.

The Grand Tour

In 1767, Townley embarked upon the

Grand Tour, visiting Naples, Paestum and Rome. Whilst in Rome, he began to collect antiquities, particularly marbles. Initially he made some bad purchases, but he learnt through his experience and became a more discerning collector, rejecting items which had been incorrectly restored.

He used Roman dealers such as Piranesi and the English dealer, Thomas Jenkins, for his purchases, which included Astragalizontes - two boys quarrelling over a game of knucklebones – which he bought from Jenkins for £400.

|

The Townley vase

© Trustees of the British Museum |

The Grand Tour again

In 1771, Townley visited Italy again – Rome, Naples and further afield into southern Italy and Sicily. Amongst the additions made to his collections on this visit was a marble bust thought to be of the nymph Clytie as well as a number of sculptures that he acquired through dealers such as Jenkins and Thomas Byres and also the painter and dealer, Gavin Hamilton.

After returning to London, Townley continued to build his collections through Jenkins and Hamilton, especially with sculptures from Hamilton’s excavations. These included the marble Townley vase and the Townley Venus, which was controversially exported in two parts by Hamilton in order to avoid papal enquiry.

Another visit to Italy

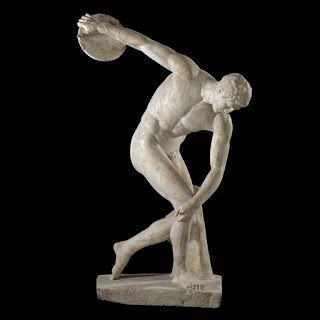

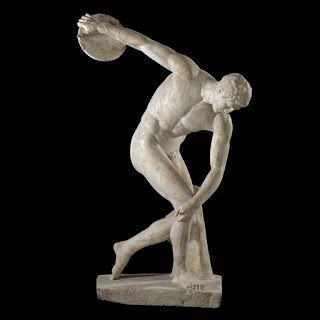

Townley spent another three months in Italy in 1777, mostly in Rome, buying from Hamilton, Jenkins and local dealers as before. After his return to London, Jenkins continued to send him antiquities, including a Roman marble copy of the bronze discus-thrower, Discobolus.

|

Discobolus

© Trustees of the British Museum |

The Townley Collection

Townley moved into 7 Park Street, a house that had been specially designed for him by Samuel Wyatt to display his collections, in 1778.2 Townley’s collection of marbles could rival any other in England and soon became a London visitor attraction. Townley welcomed visitors, either showing them round himself or, from about 1786, providing them with a catalogue of his collections.

|

The Townley Collection in the Dining Room at Park Street, Westminster

A watercolour by W Chambers (c1794-5)

© Trustees of the British Museum |

In 1783, Johan Zoffany painted Townley in his Park Street library amongst an imaginary arrangement of some of his sculptures, together with three colleagues: Charles Greville, Thomas Astle and Pierre François Hugues, known as Baron d’Hancarville, who spent years sponging off Townley whilst he catalogued his marbles. A print of this painting appears at the top of this article.

The Gordon Riots

The 1780 Gordon Riots caused great panic amongst the Catholics in London. Fearing an attack on his house, Townley fled from Park Street. Some sources say that he took the Bust of Clytie to his carriage with him; others doubt whether this was physically possible for him to have done single-handedly.

3

Recognition as an antiquarian

Townley was elected a fellow of the Society of Antiquaries and a member of the

Society of Dilettanti in 1786 and a fellow of the Royal Society in 1791.

He was elected a trustee of the

British Museum in 1791 and was able to influence the design for the planned extension to the museum.

Despite the time that Townley devoted to study and his expertise in antiquities, his only printed work was a dissertation on a Roman helmet.

Personal life

Townley never married. Perhaps he was married to his collections. He was certainly a compulsive collector. According to a financial statement from 1779, he had spent about £11,600 on antiquities. The bust of Clytie was his favourite marble and Sir Henry Ellis recorded that “he used jocosely to call it his wife”.3

|

Marble bust of a woman, possibly Antonia,

traditionally identified as the nymph Clytie

© Trustees of the British Museum |

When at his house in Park Street, he lived simply with few servants and no carriage; all available space was given over to housing his collections. But he was not parsimonious; he gave excellent Sunday dinners to his friends. He was also a talented artist and some of his sculptures are now known only from the drawings he made of them. Most of these drawings are now owned by the British Museum.

Townley’s legacy

Townley died on 3 January 1805 at his house in Park Street in London and was buried in the family vault in St Peter’s Church, Burnley, on 17 January.

He left his marbles in trust for his heir, providing that they build a gallery to display them, or otherwise, to the British Museum. In the end, all the marbles, with some terracottas and bronzes, were sold to the British Museum for £20,000. This became the core of the Graeco-Roman collection at the British Museum.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage us and help us to keep making our research freely available, please buy us a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Although the family name was generally spelt Towneley, Charles Townley signed himself Townley, dropping the extra “e”.

2. This house is now 14 Queen Anne’s Gate.

3. From The Townley Gallery of Classic Sculpture in the British Museum by Sir Henry Ellis p9 (1846).

Sources used include:

Cook, BF, Townley, Charles (1737-1805), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, (Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn, Jan 2008, accessed 12 Jan 2013)

Ellis, Sir Henry, The Townley Gallery of Classic Sculpture in the British Museum (1846)

British Museum website

Very interesting. I once visited Towneley Hall in Lancashire...

ReplyDeleteI was a 'vacuee. sent to Burnley in 1944. I recall going to a grand house on a school excursion. I don't know if it was Towneley Hall it was ....Hall but the name Towneley doesn't ring any bells.

ReplyDeleteMy memories of my time in Burnley are very vague now (I was 10 at the time) but I seem to recall going to this house via canal on a barge drawnby a horse; I certainly went on a canal that remains very clear.

I do remember seeing some large suits of armour, being quite small at the time everything appeared large.

There is a Charles Townley who was in Rome in 1773-4, stduying under the Italian artist Pompeo Bartolozzi. He was aspiring to become a portrait artist. He also purchased drawings and prints whilst there for his father's friend, Charles Rogers (1711 - 1792) FRS FSA. However, I think it another Charles Townley as his father was still alive in 1774.

ReplyDeleteI agree that it must be another Charles Townley if his father was still alive in 1774.

Delete