|

| Staircase of the British Museum in Montagu House Watercolour by George Scharf I (1845) © Trustees of the British Museum |

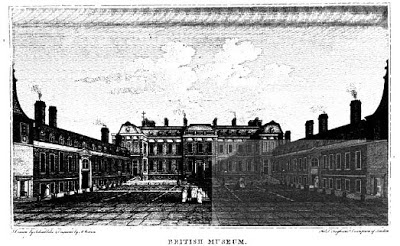

Montagu House

|

| The North Front of Montagu House and Gardens An engraving by James Simon (1714) © Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| The British Museum(2014) |

The curiositiesSuch literary gentlemen as desire to study in it, are to give in their names and places of abode, signed by one of the officers, of the committee; and if no objection is made, they are permitted to peruse any books or manuscripts which are brought to them by the messenger, as soon as they come to the reading room, in the morning at nine o’clock; and this order lasts six months, after which they may have it renewed. There are some curious manuscripts, however, which they are not permitted to peruse, unless they make a particular application to the committee, and then they obtain them; but they are taken back to their places in the evening, and brought again in the morning.1

Entry was free and granted to “all studious and curious Persons.”2

Those who come to see the curiosities, are to give in their names to the porter, who enters them in a book, which is given to the principal librarian, who strikes them off, and orders the tickets to be given in the following manner: In May, June, July and August, forty-five are admitted on Tuesday, Wednesday, and Thursday, viz. fifteen at nine in the forenoon, fifteen at eleven, and fifteen at one in the afternoon. On Monday and Friday fifteen are admitted at four in the afternoon, and fifteen at six. The other eight months in the year, forty-five are admitted in three different companies, on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday, and Friday, at nine, eleven and one o’clock.1

|

| An entrance ticket to the British Museum (1790) © Trustees of the British Museum |

All fees are prohibited, and persons who wish to view the Museum must previously enter their names and address, and the time when they would wish to see it, in a book kept by the porter. On a future day they will be supplied with tickets free of expense. Children are not admitted.3

|

| Entrance of the British Museum from Russell Street; Garden front (1761) © Trustees of the British Museum |

|

| The British Museum from London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume IV by David Hughson (1807) |

|

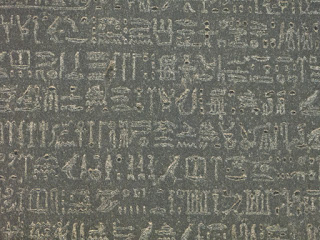

| Close-up of the Rosetta Stone in the British Museum (2014) |

The museum’s collections included:

• The Cottonian library of books and manuscripts (early 1750s)

• The Harleian collection of manuscripts (early 1750s) – purchased by parliament for £10,000

• The first ancient Egyptian mummy (1756)

• Various ethnographic artefacts from Captain Cook’s Pacific voyages, including a Tahitian mourner’s dress (1756)

• The “Old Royal Library” of the sovereigns of England – donated by George II (1757)

• The trunk of a tree gnawed by a beaver (1760)

• A stone resembling a petrified loaf (1760)

• Italian antiquities (1762) – £8410

• A live tortoise from North America (1765)

• Gustavus Brander’s fossils (1765)

• Birch’s library (1766)

• Greenwood's collection of stuffed birds – from Holland (1769) - £460

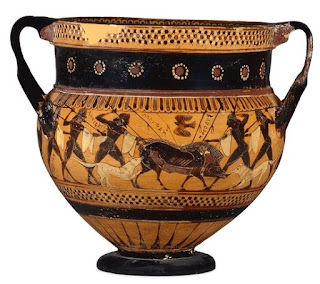

• Sir William Hamilton’s collection of Greek vases (1772) – Etruscan, Grecian and Roman antiquities - £8400

|

| The 'Hunt krater' (575-550BC) from Sir William Hamilton's collection © Trustees of the British Museum |

• Hatchett’s minerals (1798) - £700

• Tysson’s Saxon coins (1802)

• The Rosetta Stone (1802)

• The Townley collection of classical sculpture including the “Discobolus” statue and the bust of a young woman “Clytie” (1805). You can read more about Charles Townley here.

• Lansdown manuscripts (1807) - £4,925

• Bentley’s classical library (1807)

• Roberts’ coins (1810)

• Greville minerals (1810) - £13,727

• Hargrave library (1813) - £8,000

• Sculptures from the Temple of Apollo at Bassae (1815)

• The Parthenon sculptures (1816)

|

| Some of the Parthenon sculptures in the British Museum (2014) |

• Western Asiatic collection began – manuscripts, medals and antiquities (1825)

• The Nereid monument (1842)

• First stone sculptures from excavations at Nimrud site in the Middle East including the great winged bull (1850s)

• The remains of the Mausoleum of Halikarnassos (1856-7)

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Scatcherd's Ambulator (1800)

(2) The British Museum website

(3) From Crosby's A View of London (1803-4)

(4) From Hughson's London Volume VI (1809)

Sources used include:

Cox, Son and Baylis (publishers), Synopsis of the contents of the British Museum (1809)

Crosby, B , A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4)

Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume IV (1807, London)

Hughson, David, London; being an accurate history and description of the British Metropolis and its neighbourhood Volume VI (1809, London)

Leigh, Samuel, Leigh's New Picture of London (London, 1818)

Scatcherd, J, Ambulator or A Pocket Companion in a tour round London (Printed for J Scatcherd, London, 1800)

The British Museum website

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net

A priceless museum with few equals imo; top post thank you.

ReplyDeleteVery informative. Thanks, Rachel!

ReplyDeletethanks so much - lovely extra info

ReplyDeleteCan you please direct me to information about the Greenwood birds?

ReplyDeleteHi Mindy Greenwood's collection of birds is listed in the synopsis of the contents of the British Museum in 1809 as being acquired in 1769. They are described as being "a large collection of stuffed birds, in uncommon preservation." They were brought over from Holland by a person named Greenwood who had exhibited them to the public before selling them to the British Museum. If any of these birds still exist, they would have been transferred to the Natural History museum on its creation. I hope that helps.

Delete