|

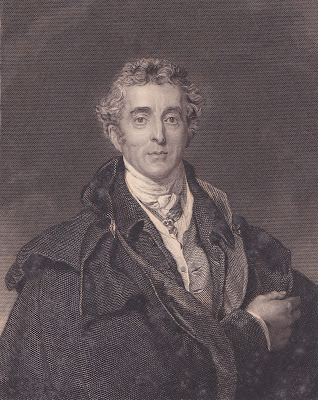

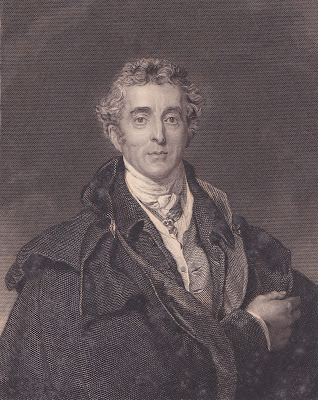

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

© Rachel Knowles - own collection |

Profile

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington (1 May 1769 – 14 September 1852), was the British military commander famous for defeating Napoleon at the Battle of Waterloo. He was also a Tory politician and British Prime Minister from 1828-30 and in 1834.

Family background

Arthur Wellesley was born in Dublin on 1 May 1769 (1), the third surviving son of Garret Wesley, 1st Earl of Mornington, and his wife Anne Hill, daughter of the 1st Viscount Dungannon. His elder brother Richard adopted the variation Wellesley as his surname in 1789 and Wellington followed suit by 1798.

Wellington’s father died when he was 12 and his domineering mother thought him inferior to his elder brothers. He played the violin and was good at arithmetic, but made little academic progress during his time at Eton College (1781-4).

In 1785, he went to Brussels with his mother and learnt French from their landlord. His mother decided that all he was fit for was the army and accordingly sent him to the Academy of Equitation at Angers in France to prepare him for his future career.

|

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

by Robert Home oil on canvas (1804)

© NPG 14712 |

Military career

Through his eldest brother’s influence, Wellington gained his first commission in the army as an ensign in March 1787. After a series of promotions, he sailed to India as a brevet-colonel in the 33rd Foot in June 1796, where he was soon joined by his eldest brother Richard who had been appointed Governor General and his younger brother Henry who was his secretary.

He returned to England in 1805 having been made a Knight of the Bath for his service in India and with a personal fortune of £42,000 amassed through his campaigns. In January 1806, he became Colonel of the 33rd Foot on the death of Lord Cornwallis.

Wellington served in the Peninsular War (1807-1814) against France under Napoleon and won significant engagements including those at Ciudad Rodrigo, Salamanca and

Vitoria, after which he was promoted to the rank of field marshal. Vastly outnumbered by the French forces, he gained a reputation as a master of defence. He ensured that the civilian population was treated well which led to good information about the movements of the French forces—a critical part of his military strategy.

After Napoleon’s abdication, Wellington was appointed British ambassador in Paris, and served at the Congress of Vienna. When Napoleon escaped from his exile on Elba in February 1815, Wellington led the allied forces against him, culminating in his most famous victory at the

Battle of Waterloo on 18 June 1815.

|

Duke of Wellington statue,

Threadneedle Street, London (2013)

|

Life in the army

Wellington was a sociable man, a prolific letter writer and a great conversationalist. Whilst serving in the army, he would often get up at six and write letters for three hours before breakfast. He would spend time with his staff officers in the morning and visit his troops or other places as necessary in the afternoon. He was surrounded by a loyal band of young gentlemen—his aides-de-camp—mostly from aristocratic families. He encouraged his officers to arrange balls and concerts and enjoyed their conversation over dinner though he had little interest in food. During the winter he hunted with his own pack.

Showered with praise

With successive victories, Wellington was awarded more and more honours. He was made Baron Douro and Viscount Wellington of Talavera (4 September 1809), Earl of Wellington (28 February 1812), Marquess of Wellington (18 August 1812) and finally Marquess Douro and Duke of Wellington (3 May 1814).

Various monuments were erected in his honour including the

Wellington Arch, Hyde Park Corner, London.

|

Wellington Arch, Hyde Park Corner, London (2013)

|

The Duke’s residences

In 1814, the House of Commons granted Wellington £400,000 to buy an estate to support his new rank and in November 1817, Stratfield Saye near Basingstoke in Hampshire was purchased for the Duke.

|

Stratfield Saye (2015)

|

In the same year, Wellington bought

Apsley House from his brother Richard at a generous price. He later employed the architect Benjamin Wyatt to remodel it to house all the trophies and other gifts that had been showered upon him.

|

| Apsley House, London (2017) |

Political career

Before Wellington went to India, he was MP for Trim in the Irish parliament (1790-7) through his family’s influence. After his return, he became a British MP in order to be able to defend his brother Richard who stood accused of maladministration and fraud during his time in India. It was when lobbying the government in this cause that Wellington had his one and only meeting with Admiral Horatio Lord Nelson.

Wellington was MP successively for Rye (1806), Mitchell (1807) and Newport on the Isle of Wight (1807-09), during which time he was Chief Secretary for Ireland.

From cabinet office to Prime Minister

When he returned to England in 1817, Wellington was made Master General of the Ordnance—the only cabinet office of a military character. But when Canning became Prime Minister in 1827, Wellington refused to serve under him and resigned. When Canning died just a few months later, Viscount Goderich replaced him, but his government did not last much longer and in 1828, Wellington was made Prime Minister.

Wellington opposed reform but yielded on the matter of Catholic emancipation in order to secure stability. However, in so doing, he alienated some of his more extreme supporters and in the face of widespread support for parliamentary reform, Wellington resigned in November 1830.

Despite Wellington’s opposition, Lord Grey’s government passed the Reform Act in 1832. Wellington was again Prime Minister for a few months in 1834 before stepping aside for Sir Robert Peel and taking on the role of Foreign Secretary instead.

|

Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

by William Salter (c1839)

© NPG Photograph © Andrew Knowles |

A duel

Wellington’s speech in favour of Catholic emancipation particularly outraged the Earl of Winchelsea who accused the Duke of introducing Popery into the government. The Duke challenged Winchelsea to a duel which took place on Battersea fields on 21 March 1829. Winchelsea did not fire; the Duke missed, but whether he deloped on purpose or missed because he was a bad shot, nobody really knows. Winchelsea apologised and the matter was closed.

A bevy of appointments

Wellington was also appointed to other roles including Lord Lieutenant of Hampshire (1820), Constable of the Tower and Lord Lieutenant of the Tower Hamlets (1826), Commander-in-Chief of the Forces (1827-8 and 1842-52), Constable of Dover Castle and Lord Warden of the Cinque Ports (1829) and Chancellor of Oxford University (1834).

A miserable marriage

The story of Wellington’s marriage is very sad. In 1793, the young Wellington proposed to Lady Catherine Pakenham but his offer was refused by her family because of his lack of prospects. In a dramatic gesture, he burnt his violin and devoted himself to his military career.

Whilst serving in India, Wellington did not communicate at all with his erstwhile love, although they heard of each other through a mutual friend, Lady Olivia Sparrow. Lady Catherine, known as Kitty, clearly thought the relationship was over as she had become engaged to someone else, although she had later broken it off. However, Lady Olivia persuaded Wellington that it was his duty to marry Kitty.

Without even seeing her, Wellington proposed to Kitty by letter in November 1805 and was accepted. They were married in Dublin on 10 April 1806 and had two sons Arthur (1807) and Charles (1808), but it was a most unhappy marriage. Kitty was no longer the lively girl that Wellington had fallen in love with. He wanted a socially able hostess, but Kitty proved to be insecure and tactless and his behaviour towards her was not kind. It was not until Kitty was dying in 1831 that Wellington finally softened towards her.

|

The Duchess of Wellington, engraved by J Thomson

after JR Swinton from Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap

Book (1849) Courtesy of Ancestryimages.com |

Friends and lovers

Wellington had relationships with numerous women including the famous courtesan Harriette Wilson. He may have had an affair with Lady Charlotte Greville, but rumours of an affair with Lady Frances Webster were groundless.3

He also had many platonic friendships with women. He enjoyed the company of Lady Shelley, the young marchioness of Salisbury and his elder son’s wife, Lady Douro, and most especially, Mrs Arbuthnot. It was rumoured that Harriet Arbuthnot was his mistress, but this was not so and her husband went to live with the Duke after her death.

|

| Mrs Arbuthnot from La Belle Assemblée (1829) |

Other friendships were fuelled by letter writing. He sent nearly 400 letters to Miss Jenkins between 1834 and 1851 and over 800 letters to Angela Burdett-Coutts.

Nicknames

Wellington was called the Beau by his officers and later the Peer, but by his less respectful troops, he was referred to as Atty (for Arthur) or Nosey (making reference to his prominent aristocratic nose).

But perhaps the most famous epithet applied to Wellington is that of the Iron Duke. The name is said to originate, not from his unemotional public demeanour, but from the iron shutters that he installed at Apsley House after pro-reform rioters broke his windows in 1831.

Illness and death

In November 1839, Wellington suffered a stroke whilst at Walmer Castle. More strokes followed with the final one proving fatal. He died on 14 September 1852 at Walmer Castle and after his body had lain in state, it was transported to London by train.

On 18 November 1852, Wellington was given a state funeral at

St Paul’s Cathedral. The procession followed a route from Horse Guards to St Paul’s via Constitution Hill and was said to have been witnessed by one and a half million people.

|

| Wellington's funeral car at Stratfield Saye |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) There appears to be some doubt as to the exact date of Wellington’s birth. A christening record for the 30 April suggests that he may have been born on the 29 April, but his parents both confirmed the date of 1 May and this was the date that Wellington himself celebrated as his birthday.

Sources used include:

Alexander, James Edward,

Life of Field Marshal, his Grace the Duke of Wellington (1840) 2 volumes

Courthope, William, editor,

Debrett's Complete Peerage of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland (1838)

Gash, Norman,

Wellesley, Arthur, 1st Duke of Wellington, (1769-1852), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2011, accessed 2 Jul 2013)

Maxwell, William Hamilton,

Life of Field-Marshal His Grace the Duke of Wellington in three volumes (1852)

History of Parliament online (accessed 09-06-15)