|

| St George's Hanover Square |

In A Perfect Match, Alicia Westlake and her mother attend the service at St George’s Hanover Square on Christmas Day 1788. Although Mrs Westlake is delighted to be introduced to the Duchess of Gordon, Alicia is disappointed to discover that Mr Merry is not there.

History

As the population of London grew, the nobility and gentry moved away from the business centre of the City. Mayfair, to the west, became a fashionable place to live. Hanover Square, built between 1716 and 1720, was the first square to be built in the newly developing area of Mayfair. It was named for the Hanoverian dynasty of the new King George I.

St George’s Hanover Square was one of fifty new churches in London commissioned by an Act of Parliament of 1711 to meet the needs of its ever growing population. The new parish of St George’s Hanover Square was carved out of the western section of the Parish of St Martin-in-the-Fields.

General William Stewart1 who had been Commander-in-Chief of Queen Anne’s forces in Ireland was a resident of Hanover Square and he donated the site on which St George’s is built, just a short distance from Hanover Square, with its entrance facing onto St George Street. General Stewart laid the first stone on 20 June 1721 and the building was certified complete on 20 March 1725. It was dedicated by Edmund Gibson, Bishop of London, three days later, on 23 March.

The church cost £10,000 to build which was raised by a tax on coals.

|

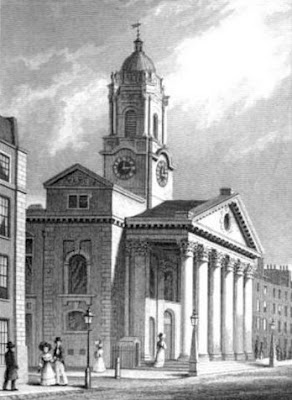

| St George's Hanover Square from Leigh's New Picture of London (1830) |

Architectural design

St George’s Hanover Square was designed by John James, a pupil of Sir Christopher Wren. According to Leigh’s New Picture of London, it is 100 feet long, 60 feet wide and 45 feet high.2

The most notable feature of the building is the portico which is considered second only to that of the church of St Martin-in-the-Fields. It has six Corinthian columns which support an entablature and pediment. In layman’s terms, the entablature is the lintel or beam that rests on the tops of the columns and the pediment is the triangular bit that sits on top.

|

| St George's Hanover Square |

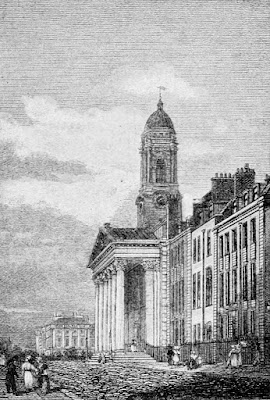

According to Shepherd:

The tower is elegantly adorned at the corners, with coupled Corinthian columns that are very lofty; these are crowned with an entablature, which, at each corner, supports two vases; and over these the tower still rises, till it is terminated by a dome, crowned with a turret, that supports a ball, over which is a vane.3

The two obelisks at either end of the steps were used to hold lamps.

|

| The tower of St George's Hanover Square |

A disappointing interior

The inside of the church was very plain compared to other churches of the same period and was compared unfavourably with its impressive exterior. In his New Picture of London, Leigh declared:

The interior of the church exhibits a total disregard of the rules of architecture.2

I wonder whether James, as a pupil of Sir Christopher Wren, was influenced by Wren’s simple design for the inside of St Paul’s which was also heavily criticised for its disappointingly plain interior.

The inside of the church has been changed over the years, firstly by reducing the height of the box pews and removing the heavy canopy over the pulpit (which can still be seen on the right in the picture below dating from 1841). Later alterations included completely remodelling the pews, lowering the pulpit, laying the black and white marble floor in the chancel (the section of the church in front of the altar) and creating a side chapel.

|

| A fashionable wedding at St George's Hanover Square in 1841 from Life In Regency and Early Victorian Times by EB Chancellor (1926) |

The altarpiece

The reredos or altarpiece is a large painting of The Lords’ Supper. Originally this was thought to be the work of Sir James Thornhill (1675-1734), but has since been confirmed as the work of William Kent (1685-1748). The carvings around the picture are from the workshop of Grinling Gibbons, but not by the man himself, as he died in 1720.

Above the altar is a Venetian window, but the stained glass it now holds is not original. It comes from Antwerp and dates back to 1525. It was acquired by the 1st Marquess of Ely but never used by him and sold to St George’s in 1840.

There are seven silver lamps hanging in the church representing the seven lamps described in the book of Revelation.

The organ

The first organ cost £500 and was installed in 1725. The three central towers of the organ casing today are original. In 1761, the organ was replaced by John Snetzler for the price of £300 and the old organ pipes! It has been replaced and expanded over the years and the current organ is particularly suited to baroque music – an important factor as the Annual London Handel Festival is held at St George’s.

The Georgian rectors of St George's

The rectory of St George’s Hanover Square was in the gift of the Bishop of London and was very valuable. According to the Clergy List for 1891, it was worth £1,120 a year. The prospect was too alluring for one spendthrift minister – the Reverend William Dodd, a chaplain in ordinary to the King. In 1774, Dodd unsuccessfully tried to bribe the Lord Chancellor’s wife to appoint him to the rectory.4

It was common practice in the 18th century for ministers to be pluralists – that is, hold multiple posts – and all the rectors during the Georgian period held other positions as well as that of rector of St George’s Hanover Square.

The rectors during the Georgian period were:

Andrew Trebeck (1725-59) who was also the vicar of Croydon and held the living of Shelley in Essex.

Charles Moss (1759-1774) who was the Bishop of St David’s, but resigned as rector of St George’s when he was appointed Bishop of Bath and Wells in 1774.

Henry Reginald Courtenay (1774-1803) who was the Bishop of Bristol and Exeter and also held other roles.

Robert Hodgson (1803-1845) who was Dean of Chester and Carlisle and also held other posts.

|

| St George's Hanover Square from London and its environs in the 19th century by T H Shepherd (1829) |

Workhouses and schools

The parish workhouse was situated in Mount Street. The conditions were such that around half the children born in or received into the workhouse between 1750 and 1755 died. An extra house was bought in 1785 as the existing workhouse was full.

In his will, General Stewart left 5000 Irish pounds – approximately £4,500 – with which to establish a charity school in the parish which opened in 1742. Two further schools teaching practical skills were opened in 1804 and 1815 with money raised by the parish.

|

| St George's Hanover Square from The history of Methodism by J F Hurst (1902) via Internet archive on Flickr |

A fashionable wedding venue

The location of St George’s Hanover Square, situated in the heart of the richest part of London, made it a very fashionable place to get married. The first wedding took place on 30 April 1725 and less than 40 marriages took place in the first year. The numbers rose to a peak in the middle of the Regency period with an incredible 1063 weddings taking place in 1816! This figure was quoted on a signboard in the church and looking through the registers, I haven’t checked this total, but I did note that 11 couples were married on 22 April, 12 couples on 3 June and nine couples on Christmas Day!

Some of the famous people who got married at St George’s Hanover Square were:

8 March 1769 Evelyn Pierpoint, Duke of Kingston, and Elizabeth Chudleigh. They were married by S Harper of the British Museum by special licence from the Archbishop of Canterbury.

Although Elizabeth Chudleigh claimed to be single, her first husband, Augustus Hervey, later 3rd Earl of Bristol, Lady Elizabeth Foster’s uncle, was still alive. Elizabeth Chudleigh was convicted of bigamy in 1776.

11 February 1773 The architect Henry Holland and Bridget Brown, daughter of Capability Brown, by licence.

18 January 1781 The painter Richard Cosway and Maria Cecilia Louisa Hadfield, a minor. By licence and with consent of her mother Isabella Hadfield. According to Clinch, the bride was given away by Charles Townley, the collector of the Townley marbles. (5)

5 December 1793 Augustus Frederick and Augusta Murray. This seemingly innocent entry was actually the marriage of the Duke of Sussex and Lady Augusta Murray. This marriage was declared null and void on 14 July 1794 as it contravened the Royal Marriage Act and the church officials had to answer for not having enquired more fully into the residence of the couple when the banns were posted.

|

| Augustus, Duke of Sussex from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany by John Watkins (1827) |

1 May 1797 Edward Smith Stanley, Earl of Derby, widower, and the actress Elizabeth Farran, spinster, by special licence in the dwelling house of the Earl of Derby in Grosvenor Square.6

17 December 1798 The architect John Nash and Mary Ann Bradley

11 May 1799 The comedian and entertainer Joseph Grimaldi and Maria Hughes

23 May 1804 George Villiers (commonly called Lord Viscount Villiers), later 5th Earl of Jersey, of St Marylebone, bachelor, and Lady Sarah Fane, of this parish, spinster, a minor. Married by special licence with the consent of her father, John, Earl of Westmoreland, in his dwelling house in Berkley Square.

|

| Lady Jersey from a print on display at Osterley Park |

17 May 1809 George Lamb, third son of Peniston, Lord Viscount Melbourne, and Caroline Rosalie Adelaide St Jules, of this parish. Married in Devonshire House in this parish by special licence from the Archbishop of Canterbury. Caroline St Jules was the illegitimate daughter of Lady Elizabeth Foster and the Duke of Devonshire who were witnesses to the marriage.

24 March 1814 Percy Bysshe Shelley and Harriet Shelley, formerly Harriet Westbrook, spinster, a minor, both of this parish, by licence. There is a note in the register to say that the parties had been already married to each other according to the Rites and Ceremonies of the Church of Scotland. This took place in 1811 after they had eloped together. This time the marriage was with the consent of her father John Westbrook, but it was ill-fated; just four months later Percy Shelley abandoned Harriet and ran away with Mary Wollstonecraft Godwin.

It is worth noting that there is one marriage sometimes quoted as taking place at St George’s Hanover Square that I cannot find any record of in the registers – the marriage of Sir William Hamilton and Emma Hart.7 According to Morson, their marriage on 6 September 1791 took place at the church of St Marylebone.8

Burials

There was no space for a churchyard next to St George’s, so its first burial ground was situated next to its workhouse in Mount Street. This was full by 1762 and another burial ground was opened at Bayswater which was used until 1854. It is described variously as being near the Tyburn turnpike and just off Oxford Street, near the Marble Arch.

Important people who were buried there include:

Laurence Sterne, author of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy (1713-1768). His body was later stolen by body snatchers!

Sir Thomas Picton (1758-1815) who was killed at the Battle of Waterloo but his body was afterwards removed to St Paul’s Cathedral.

Mrs Ann Radcliffe (1764-1823), author of The Mysteries of Udolpho.

Both burial grounds have now been cleared. The Mount Street site has been turned into a park and the Bayswater site was sold for redevelopment.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) Sometimes spelt Steuart.

(2) From Leigh's New Picture of London (1830).

(3) From London in the Nineteenth Century, illustrated by a series of views by TH Shepherd (1829).

(4) Dodd’s plan misfired and he was dismissed from all his existing positions. Later he was convicted of forging a bond in order to pay his debts and despite widespread public support, he became the last person to be hanged at Tyburn for forgery on 27 June 1777.

(5) From Mayfair and Belgravia: being an historical account of the parish of St George, Hanover Square by George Clinch (1892).

(6) Sometimes spelt Farren.

(7) On a signboard in the church and in Mayfair and Belgravia: being an historical account of the parish of St George, Hanover Square by George Clinch (1892).

(8) From Morson, Geoffrey V, Hamilton, Sir William (1731-1803), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn May 2009, accessed 12 Jan 2013).

Sources used include:

Chancellor, E Beresford, Life in Regency and Early Victorian Times (1926)

Chapman, John H (ed) The Register book of marriages belonging to the Parish of St George, Hanover Square in the County of Middlesex in 4 volumes Vol 1 1725-87 (1886-97)

Chapman, John H (ed) The Register book of marriages belonging to the Parish of St George, Hanover Square in the County of Middlesex in 4 volumes Vol 1 1725-87 (1886-97)

Clinch, George, Mayfair and Belgravia: being an historical account of the parish of St George, Hanover Square (1892)

Leigh, Samuel, Leigh's New Picture of London (1830)

Morson, Geoffrey V, Hamilton, Sir William (1731-1803), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn May 2009, accessed 12 Jan 2013)

Shepherd, Thomas H, London in the Nineteenth Century, illustrated by a series of views (1829)