|

| A map of Vauxhall Gardens from The Mirror (1830) |

During the Georgian period, it was fashionable to visit pleasure gardens. Some of the most famous gardens were those at Vauxhall. For the modest sum of a shilling, members of the public from all walks of life could escape from the hubbub of the city and visit the gardens and sample its amusements.

1

In the first book in

The Merry Romances,

A Perfect Match, Mrs Westlake and Alicia visit Vauxhall Gardens in pursuit of the Duke of Wessex.

|

| Vauxhall Gardens from The Microcosm of London (1808-10) |

The Cascade

One of the most popular attractions of Vauxhall Gardens was the Cascade – an artificial waterfall. It first opened in 1752 and was situated in the woodland area near the Centre Cross Walk. It was the central feature of a three-dimensional landscape and gave the appearance of real water by means of a system of tin sheets on belts which moved as the mechanism was turned by a team of men. Clever lighting accompanied by the sound of roaring water made it a spectacle not to be missed.

Erasmus Darwin wrote in 1756:

The artificial Water-fall at Vaux Hall I apprehend is done by pieces of Tin, loosely fix’d on the Circumferences of two Wheels. It was the Motion not being perform’d at Bottom in a parabolic Curve that first made me discover it’s not being natural.2

To enhance the mystery of the Cascade, during the daytime it was hidden by a curtain or screen decorated with a landscape painting. As darkness fell, this was drawn back dramatically to build the anticipation for the show. The Cascade only operated for around ten to fifteen minutes each evening and a bell was rung to announce the nightly performance. Some reports state that this was at nine o’clock, whilst others say ten, so I think it must have varied over time.

|

| Vauxhall Gardens (2012) |

Carver’s Cascade

The Cascade was regularly upgraded and improved to keep the audience interested. In 1787, the scene was repainted by Robert Carver. The newly painted landscape was accompanied by a storm. The Times on 8 May 1783 reported:

The new Cascade, with the Land Storm, might have been played off—but we did not observe it.3

Another newspaper report described the Cascade as:

Grand, and the effect awful; the fall of water is accompanied by a storm, executed with every appearance of reality and nature.4

|

Print of Vauxhall Gardens from signboard in Vauxhall Gardens (2012)

|

Contemporary descriptions of the Cascade

An eyewitness account from 1762 said:

A most beautiful landscape in perspective of a fine open hilly country with a miller’s house and a water mill, all illuminated by concealed lights; but the principal object that strikes the eye is a cascade or water fall. The exact appearance of water is seen flowing down a declivity; and turning the wheel of the mill, it rises up in a foam at the bottom, and then glides away. This moving picture attended with the noise of the cascade has a very pleasing and surprising effect on both the eye and ear.5

In his Picture of London for 1802 John Feltham wrote:

At ten o'clock, a bell announces the opening of a beautiful cascade, which, exhibiting some rural and comic scenery, delights and surprizes.6

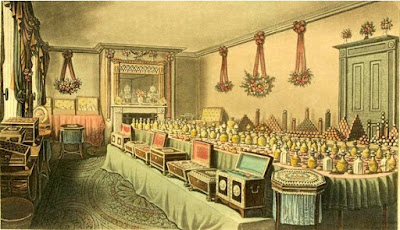

The Microcosm of London (1808-10) described the Cascade:

At the end of the first act of the grand concert, which is usually about ten o’clock, a bell is rung by way of signal for the exhibition of a beautifully illuminated scene, called the cascade. A dark curtain is then drawn up, which discloses a very natural view of a bridge, a water-mill, and a cascade; a noise similar to the roaring of water is also well imitated; while coaches, waggons, soldiers and other figures, are exhibited crossing the bridge with the greatest regularity. This agreeable piece of scenery continues about ten minutes.7

The Mirror (1830) said:

To the left, in a line since called ‘the Dark Walk’, near the pavilions, was the artificial Cascade, after wards displaced by the Cottage scene, with the old man smoking, &c.; and at the extremity of the walk was some other decoration. The Cascade was, doubtless, one of the original exhibitions; for in the Connoisseur dated Thursday, May 15, 1755, it is mentioned, though not as a novelty — “At Vauxhall the artificial ruins are repaired; the cascade is made to spout with several additional streams of block-tin; and they have touched up all the pictures, which were damaged last season by the fingering of those curious connoisseurs, who could not be satisfied without feeling whether the figures were alive.”8

|

Vauxhall Gardens by Rowlandson from signboard in Vauxhall Gardens (2012)

|

The final years

The Cascade was later changed again to portray the tidal race and watermill at London Bridge and other scenes and it continued to be popular until its demolition prior to the Ballet Theatre being built in the 1820s. Walford stated that at one stage the Cascade was referred to as the Cataract9, but I have not come across any contemporary records that use this name for it.

There was still a cascade on the 1841 plan of Vauxhall Gardens on the site of the Chinese Pavilions, but this was probably the real waterfall created for the birthday of Queen Adelaide in 1835.

The Cascade in fiction

Evelina

In Fanny Burney’s Evelina (1778), Evelina visits Vauxhall Gardens:

As we were walking about the orchestra, I heard a bell ring; and, in a moment, Mr. Smith, flying up to me, caught my hand, and, with a motion too quick to be resisted, ran away with me many yards before I had breath to ask his meaning, though I struggled as well as I could, to get from him. At last, however, I insisted upon stopping: “Stopping, Ma'am!”cried he, “why we must run on or we shall lose the cascade!”

And then again he hurried me away, mixing with a crowd of people, all running with so much velocity, that I could not imagine what had raised such an alarm. We were soon followed by the rest of the party; and my surprise and ignorance proved a source of diversion to them all, which was not exhausted the whole evening. Young Branghton, in particular, laughed till he could hardly stand.

The scene of the cascade I thought extremely pretty, and the general effect striking and lively.10

|

| Vauxhall display at Museum of London (2013) |

A Perfect Match

In A Perfect Match, Mrs Westlake and Alicia visit Vauxhall Gardens in the summer of 1789:

At the appointed time, a bell rang to announce the nightly performance of the Cascade. Mrs Westlake immediately expressed a desire to see the artificial waterfall that had been so much improved since the days of her youth. She had heard that the show now included a storm. Mr Lamont readily rose to his feet and, with a lady on each arm, led them to the area of woodland where the famous spectacle was situated.

As soon as she reasonably could, Alicia withdrew her arm from Mr Lamont’s grasp and moved a little away from her mother and her companion so that she could watch the Cascade in peace.

“It is done by mechanics,” a voice behind her said.

Alicia recognised it instantaneously. Despite her recent doubts over his morals, she was heartily glad to see him. “Mr Merry, I quite thought you had gone out of town.”

“And I thought you had become part of the Duke’s party.”

Alicia blushed. “I …my mother…”

“It is all achieved by a mechanical device that gives the illusion of a waterfall,” Mr Merry said, changing the subject.

“Oh. But maybe I just want to enjoy the spectacle instead of analysing how it works.”

Mr Merry considered this. “That does not seem very likely, but if the illusion gives you pleasure, then by all means, be amused. I could explain how it works, but if you are not interested, I will cease to bother you with my company.”

Alicia was torn. She had seen so little of Mr Merry in the past few weeks and though she knew she should not encourage his attentions, she did not want him to go. Besides, she was inquisitive and wanted to know how it worked. Her mother was too absorbed to pay any heed.

“Very well. Tell me,” she said.

Mr Merry grinned, making his face seem much younger. He proceeded to explain, very clearly and succinctly, the device behind the Cascade.

“You would make an excellent teacher, Mr Merry,” she exclaimed.

“But my job is so easy when I have only one pupil and she is eager to learn.”

“Alicia? Where are you?” Mrs Westlake’s voice called out. The Cascade’s performance was over and she had finally noticed that her daughter was not standing next to her as she had assumed.

“Mother, I…” How was she going to explain Mr Merry’s presence? It had all the appearance of a secret assignation. She turned to say goodbye, but Mr Merry had already gone.11

|

| Vauxhall display at Museum of London (2013) |

The Citizen of the World

The Cascade was referred to as the water-works in Oliver Goldsmith’s The Citizen of the World (1820):

Mrs Tibbs was for keeping the genteel walk of the garden, where, she observed, there was always the very best company; the widow, on the contrary, who came but once a season, was for securing a good standing-place to see the water-works, which, she assured us, would begin in less than an hour at furthest.

But the widow was destined not to see the water-works.

Mr Tibbs, now willing to prove that his wife’s pretensions to music were just, entreated her to favour the company with a song” and “At last then the lady complied, and after humming for some minutes, began with such a voice and such affectation, as, I could perceive, gave but little satisfaction to any except her husband. He sat with rapture in his eye, and beat time with his hand on the table. You must observe, my friend, that it is the custom of this country, when a lady or gentleman happens to sing, for the company to sit as mute and motionless as statues. Every feature, every limb, must seem to correspond in fixed attention, and while the song continues they are to remain in a state of universal petrefaction. In this mortifying situation we had continued for some time, listening to the song, and looking with tranquillity, when the master of the box came to inform us, that the water-works were going to begin. At this information I could instantly perceive the widow bounce from her seat; but, correcting herself, she sat down again, repressed by motives of good breeding. Mrs Tibbs, who had seen the water-works an hundred times, resolving not to be interrupted, continued her song without any share of mercy, nor had the smallest pity on our impatience. The widow’s face, I own, gave me high entertainment; in it I could plainly read the struggle she felt between good-breeding and curiosity; she talked of the water-works the whole evening before, and seemed to have come merely in order to see them; but then she could not bounce out in the very middle of a song, for that would be forfeiting all pretensions to high life, or high-lived company, ever after. Mrs Tibbs therefore kept on singing, and we continued to listen, till at last, when the song was just concluded, the waiter came to inform us that the water-works were over. “The water-works over!” cried the widow, “the water-works over already, that's impossible, they can’t be over so soon!”12

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) The entrance price to the gardens was fixed at one shilling from 1736 until 1792 when it was raised to two shillings. In 1812, the cost was four shillings.

(2) From a letter written by Erasmus Darwin to his friend Albert Reimarus in 1756 in The Collected Letters of Erasmus Darwin (2007).

(3) From Vauxhall Masquerade Times London, England 18 May 1787 3. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 13 Oct. 2015.

(4) From an unknown newspaper report dated 24 May 1787 in Coke, David and Borg, Alan, Vauxhall Gardens, a history (2011).

(5) A report from 1762 in Coke, David and Borg, Alan, Vauxhall Gardens, a history (2011).

(6) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London (1802).

(7) From Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Vol 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904).

(8) From The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1830).

(9) From Edward Walford, 'Vauxhall', in Old and New London: Volume 6 (London, 1878), pp. 447-467 http://www.british-history.ac.uk/old-new-london/vol6/pp447-467 [accessed 13 October 2015].

(10) From Burney, Fanny, Evelina or the history of a young lady’s entrance into the world (1778).

(11) From Knowles, Rachel, A Perfect Match (2015).

(12) From Goldsmith, Oliver, The Citizen of the World (1820).

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Vol 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Burney, Fanny, Evelina or the history of a young lady’s entrance into the world (1778)

Coke, David and Borg, Alan, Vauxhall Gardens, a history (2011)

Darwin, Erasmus, The Collected Letters of Erasmus Darwin, Cambridge University Press, 2007, Letter 56-6)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London (1802)

Goldsmith, Oliver, The Citizen of the World (1820).The Mirror of Literature, Amusement and Instruction (1830)

Knowles, Rachel, A Perfect Match (2015)

The Times Digital Archive - as referenced in notes above.

Walford, Edward 'Vauxhall', in Old and New London: Volume 6 (London, 1878), pp. 447-467 [accessed 13 October 2015].

Photographs © RegencyHistory.net