|

| Steam engines in the Science Museum, London (2016) |

A brief history of the steam engine

The term ‘steam engine’ probably brings to mind the image of a majestic locomotive, of the sort now relegated to heritage railways, museums and the occasional movie appearance.

Back in 1712, when ironmonger and Baptist preacher Thomas Newcomen (1664-1729) created the first commercially viable steam engine, its function was to pump water out of coal and tin mines. Newcomen adapted the experimental work of others to create and patent a machine that proved popular with mine owners.

Newcomen probably referred to his machine as a ‘fire engine’. The name of the business through which he and others built the engines was called ‘Proprietors of the invention of raising water by fire’. The term ‘atmospheric engine’ is also used to describe Newcomen’s invention.

|

| A working replica of Newcomen's steam engine at the Black Country Living Museum, Dudley (2014) |

James Watt pushes steam power forward

Other engineers refined Newcomen’s designs, particularly John Smeaton (1724-1792). However, being relatively low powered, it proved unsuitable for being used to power anything other than pumps. As a result, its use was limited to the mining industry.

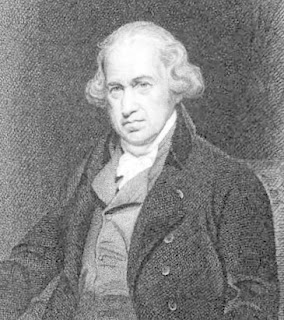

The next major development came with Scottish instrument maker James Watt (1736-1819) who became fascinated by the potential of steam power.

|

| James Watt from the European Magazine and London Review (1820) |

In 1763 he was asked to restore to operation a model of Newcomen’s engine that belonged to the University of Glasgow. In doing so, he realised that the design was grossly inefficient. By 1765 he had designed a much more efficient engine but it took another ten years for him to find ironworkers with the skills needed to build it.

In 1775 Watt began working with Matthew Boulton (1728-1809), manufacturer and owner of the Soho Works where Watt was finally able to build his steam engine. This led to the formation of Boulton and Watt, the business that built the steam engines which powered much of the industrial revolution. The firm employed another Georgian inventor, William Murdoch (1754-1839), who is credited with the invention of gas lighting in the early 1790s.

|

| Bell-crank engine by Bolton and Watt c1810 in the Science Museum, London (2016) |

The significance of Watt’s work is described in this Memoir:

The original inventor of the steam-engine undoubtedly laid the foundation for all the wonderful effects that are now produced by that mighty machine; but while it was merely employed for the drawing of water from mines, it was of but little importance, compared to what it is at the present day: and that change, from a small degree of importance, to that of the very first-rate degree, was exclusively almost the work of Mr Watt.1

|

| Statue of Boulton, Watt and Murdoch, Birmingham (2013) |

While Newcomen and then Watt were busy with static steam engines, others dreamt of harnessing this new power for transport. Richard Trevithick (1771-1833) built and demonstrated a steam road vehicle in 1801 at Camborne in Cornwall.

In doing so, Trevithick overcame the huge challenge of making an engine small enough to fit on a vehicle, and that meant working with a potentially dangerous high pressure steam engine.

|

| Richard Trevithick from Life of Richard Trevithick by Francis Trevithick (1872) |

The Watt engine operated at low pressure. Boulton and Watt opposed the use of high pressure because of the risk of explosion. Their concern seemed justified when, in 1803, four men died when one of Trevithick’s high pressure static engines exploded at Greenwich.

Trevithick responded by introducing safety valves. That same year his London Steam Carriage made a journey between Holborn and Paddington. In 1808, Trevithick exhibited a new locomotive called Catch-Me-Who-Can on a circular track in London. Anyone could ride on the train for a mere shilling, but the track broke after a couple of months and the enterprise was abandoned.

|

| Trevithick's London railway and Catch-Me-Who-Can locomotive of 1808 from Life of Richard Trevithick by Francis Trevithick (1872) |

While he proved the concept of using high-pressure steam to drive vehicles, none of Trevithick’s innovations went beyond its test run.

Stream engines take to the rails

The first commercially viable steam locomotive ran at Middleton Colliery, near Leeds, in 1812. It was designed and built by Matthew Murray (1765-1826) who adapted a Trevithick model with so much success, that he built three more. They were in service for around twenty years, although during that time, two blew up, killing their drivers.

In the early 1800s, forward-thinking mine owners could see, as their predecessors had done a century earlier, that introducing steam powered machines could save them money. In the early 1700s the machines had just powered pumps; now they could replace horses and men as transport.

George Stephenson (1781-1848) worked in collieries, looking after steam engines. In 1814, inspired by Murray’s locomotive, he began designing his own and may have built up to 16 to work at Killington Colliery. In 1820 he was hired to build the first railway to operate without animal power, at Hetton Colliery.

The world’s first passenger railway, the Stockton and Darlington Railway, was initiated by Act of Parliament in 1821 and Stephenson built the first locomotive to run on it, named Locomotion.

As the Georgian era due to close, steam power was set to revolutionise the world by driving ever increasing numbers of trains, ships and industrial machines. The last notable landmark before the Victorian age was the Rainhill Trials of 1829, where the locomotive for the new Liverpool and Manchester Railway was chosen.

Stephenson entered with an engine designed largely by his son, Robert (1803-1859). His locomotive, Rocket, won the day and secured its place in railway history.

|

| Stephenson's Rocket, Science Museum, London (2016) |

Places where you can find examples of Georgian steam engine history

Black Country Living Museum: In the 1980s the museum built a working replica of a Newcomen steam engine. While it’s not a Georgian survivor, it operates on certain days and gives a feel of how it was to be near an early steam engine.

Crofton Pumping Station: A unique example of a Boulton and Watt engine still used for its original purpose, pumping water on the Kennet and Avon canal. Installed in 1812, it’s long been replaced by modern pumps, but it’s still used a few times a year.

Dartmouth Circus, Birmingham: An 1817 Boulton and Watt blowing engine has been installed on a traffic roundabout.

Dartmouth Museum: Home to a 1725 Newcomen engine.

Darlington Railway Museum: The first steam engine to pull a passenger car on the Stockport and Darlington Railway, Locomotion No.1, is displayed here.

Elsecar Heritage Centre: Here you can see the only Newcomen engine still in its original location. Built in 1795, it’s recently been restored to working order.

Henry Ford Museum: A Newcomen engine from 1750-60 is on display.

Hunterian Museum, Glasgow: The model Newcomen engine worked on by James Watt is in the museum collection.

Kinneil House, Scotland: Here James Watt worked on the model Newcomen engine and developed his ideas for a new design. The remains of his cottage can still be viewed.

Locomotion, Shildon: Part of the National Railway Museum, the Shildon site is home to Sans Pereil, one of the engines that lost to Rocket at the 1829 Rainhill Trails.

Powerhouse Museum, Sydney: This claims to have the earliest surviving rotative steam engine in the world, a Boulton and Watt from 1785, originally used at Whitbread’s Brewery in London.

Science Museum, London: Unsurprisingly, this is now the home of several landmark inventions including Stephenson’s Rocket, an example of Trevithick’s high-pressure engine from 1806 and several Boulton and Watt engines including Old Bess, an early beam engine built in 1777.

Thinktank, Birmingham: The Smethwick Engine is the oldest working example of a Boulton and Watt machine, dating from 1779.

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who wrote this blog.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Memoir of the late James Watt, Esq, FRS, in Philosophical Magazine Series 1, LXXII (1819)

Sources used include:

Cookson, Gillian, Murray, Matthew (1765-1826), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; accessed 25 Feb 2016)

Kirby, MW, Stephenson, George (1781-1848), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 6 Oct 2012)

Kirby, MW, Stephenson, Robert (1803-1859), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 25 Feb 2016)

Payton, Philip, Trevithick, Richard (1771-1833), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Oct 2007, accessed 25 Feb 2016)

Tann, Jennifer, Watt, James (1736-1819), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn May 2007, accessed 6 Oct 2012)

Tilloch, Alexander and Taylor, Richard, Memoir of the late James Watt, Esq, FRS, in Philosophical Magazine Series 1, LXXII (1819)

Trevithick, Francis, Life of Richard Trevithick (1872)

(1) From Memoir of the late James Watt, Esq, FRS, in Philosophical Magazine Series 1, LXXII (1819)

Sources used include:

Cookson, Gillian, Murray, Matthew (1765-1826), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; accessed 25 Feb 2016)

Kirby, MW, Stephenson, George (1781-1848), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 6 Oct 2012)

Kirby, MW, Stephenson, Robert (1803-1859), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 25 Feb 2016)

Payton, Philip, Trevithick, Richard (1771-1833), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Oct 2007, accessed 25 Feb 2016)

Tann, Jennifer, Watt, James (1736-1819), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn May 2007, accessed 6 Oct 2012)

Tilloch, Alexander and Taylor, Richard, Memoir of the late James Watt, Esq, FRS, in Philosophical Magazine Series 1, LXXII (1819)

Trevithick, Francis, Life of Richard Trevithick (1872)

Photos © Andrew Knowles RegencyHistory.net