The oldest part of the Tower of London dates back to the time of William the Conqueror. William was crowned king of England in London on Christmas Day 1066 following his decisive victory at the Battle of Hastings a few months earlier. Keen to ensure control of his capital city, he commissioned the construction of a fortress—what is now known as the White Tower. It was begun in the 1070s and completed after his death, by about 1100.

Subsequent monarchs added more buildings and extended the Tower’s fortifications, turning it into the imposing military stronghold that it is today.

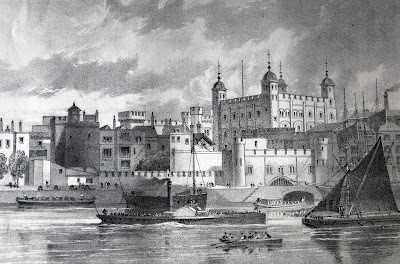

|

| The Tower of London from Old and New London by W Thornbury (1873) |

The Tower of London is situated on the north bank of the Thames, at the extremity of the city. Its extent within the wall is twelve acres and five roods. The exterior circuit of the ditch which entirely surrounds it, is 3,156 feet. The ditch, on the side of Tower-hill, is broad and deep; on the side next to the river it is narrower. A broad and handsome wharf runs along the banks of the river, parallel with the Tower, from which it is divided by the ditch. On the wharf is a platform, mounted with sixty-one pieces of cannon, nine-pounders. These are fired on state holidays; and in time of war, on all victories gained by the army or navy. At each end of the wharf is a wooden gate, which divides it from the streets, and is open only during the day.

From the wharf into the Tower, is an entrance by a draw-bridge. Near this is a cut, connecting the river with the ditch, having a water-gate, called Traitor's Gate, state prisoners being formerly conveyed by this passage from the Tower to Westminster, for trial. Over Traitor's Gate is a building containing the water-works that supply the fortress with water.

The principal entrance to the Tower is on the west, and is wide enough to admit a carriage. It consists of two gates on the outside of the ditch; a stone bridge built over the ditch, and a gate within the ditch.

The white tower is a large square building, situated in the centre of the fortress. On the top are four watch towers, one of which, at present, is used as an observatory. Neither the sides of this building, nor the small towers, are uniform. The walls are not covered with plaister, but white-washed, as will be supposed from its name. 1

|

| The moat of the Tower of London c1800 from Old and New London by W Thornbury (1873) |

Although used occasionally as a royal residence, this was never the Tower’s chief purpose. It was originally designed to advertise the king’s dominance and to protect London against potential uprisings. The security of the buildings within the outer walls led to the Tower of London being used to house the Crown Jewels, the Royal Mint, the Board of Ordnance, Ordnance Survey, the Records Office and, of course, state prisoners.

The Tower as a prison

Those held captive in the Tower of London were no ordinary prisoners. They were enemies of the state, imprisoned on grounds of treason. Despite its somewhat gruesome reputation, only 22 executions have taken place within the Tower walls, including those of two of Henry VIII’s wives, Anne Boleyn and Catherine Howard, and the unfortunate Lady Jane Grey. Another queen, the young Elizabeth I, was imprisoned in the Tower by her half-sister Mary.

Many of the towers have been used to house prisoners over the years, notably the Beauchamp Tower and the Salt Tower, which both contain 16th and 17th century graffiti giving witness to their history as prison cells.

In 1483, the 12-year-old Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York, were residing in the Tower of London when they disappeared. It was widely believed that they had been murdered by their uncle, Richard III, giving rise to the legend of ‘The Princes in the Tower’. The tower traditionally associated with their disappearance was nicknamed the Bloody Tower.

|

| The Tower of London (2016) |

Georgian prisoners

The Tower was still being used as a prison during the Georgian period.

The Tower is used as a state prison, and in general the prisoners are confined in the warders' houses, but by application to the privy-council, they are usually permitted to walk on the inner platform, during part of the day, in company of a warder.

- The Jacobite Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat, was imprisoned in the Tower following the Battle of Culloden in 1746. He was the last person to be executed on Tower Hill, on 9 April 1747.

- Lord George Gordon was imprisoned in the Tower for six months for his role in instigating the anti-Catholic Gordon Riots of 1780.

- Radical English reformist politician Sir Francis Burdett was imprisoned in the Tower from April to June 1810, accused of breach of privilege by the House of Commons.

The Curiosities of the Tower

Although the Tower of London was a working prison and the base for various government departments, it was also a Regency-era tourist attraction, open to the public, who could see inside many of the buildings on payment of the required fees.

- The Lions, and other Wild Beasts – one shilling.

- The Spanish Armory – 'the trophies of the famous victory of Queen Elizabeth over the Spanish Armada'.

- The Small Armory – 'contains complete stands of arms for no less than 100,000 men'.

- The Volunteer Armory (in the White Tower) – 'contains arms piled in beautiful order for 30,000 men, with pikes, swords, &c. in immense numbers, arranged in stars and other devices'.

- The Sea Armory (also in the White Tower) – 'contains arms for nearly 50,000 sailors and marines'.

- Royal Train of Artillery (part of this is kept on the ground floor, under the small armory) – 'The artillery is ranged on each side, a passage ten feet in breadth being left in the centre'.

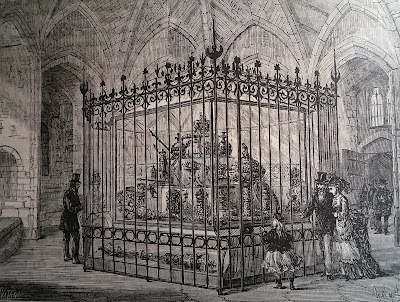

- Horse Armory – 'The kings of England, on horseback, are shewn in the following order: George II … George I … William III…'

For the Spanish Armory, Small Armory, Train of Artillery, and Horse Armory, the price is one shilling only.

|

| The Horse Armour at the Tower of London from Ackermann's Microcosm of London (1808-10) |

- The Jewel-office - one shilling per person in company or one shilling and sixpence for a single person. The Crown Jewels that could be seen included the Imperial Crown 'with which the kings of England are crowned', the Golden Globe, the Golden Sceptre and 'the Crown of State, that his majesty wears in parliament'.

Independently of several of the jewels, which are inestimable, the value of the precious stones and plate contained in this office, is not less than two millions sterling.

|

| The Jewel Tower at the Tower of London from Old and New London by W Thornbury (1873) |

- The Mint – 'Visitors are not permitted to see any part of the Mint.'

- The Chapel – 'contains a few ancient monuments' and 'may be seen by applying to the pew-opener, at any time, for a small fee'.

The Tower of London today

|

| The Tower of London (2016) |

The Grand Storehouse was destroyed by fire in 1841, along with around 60,000 objects which were on display, and was replaced by the Waterloo Barracks.

In 1845, whilst the Duke of Wellington was Constable of the Tower, the moat, which had become smelly and unhealthy, was drained.

During the 19th century, the institutions of the Tower moved out. The Royal Mint was transferred to a new purpose-built facility on Tower Hill in 1812 and the Ordnance Survey relocated to Southampton after the fire of 1841. The functions of the Office of the Ordnance were transferred to the War Office in the 1850s; the Tower Records Office was closed in 1858 after handing over its records to the Public Records Office.

The Crown Jewels

One function of the Tower of London remains—the Crown Jewels are still stored within its walls. Since 1967, the Crown Jewels have been on display in the Jewel House in the Waterloo Barracks.

|

| Entrance to the Jewel House at the Tower of London (2016) |

The White Tower

|

| The White Tower, Tower of London (2016) |

|

| Part of the Royal Armouries' collection on display in the White Tower (2016) |

|

| The Line of Kings exhibition in the White Tower (2016) |

There is an exhibition about the history of the Royal Mint at the Tower.

|

| Mint Street, Tower of London (2016) |

|

| Raven at the Tower of London (2016) |

I've written a separate blog post about the Royal Menagerie at the Tower of London here.

The Warders give informative tours of the Tower to visitors, dressed in their distinctive uniform.

Walk the walls

Traitors' Gate

|

| A wall walk at the Tower of London with Tower Bridge in the background (2016) |

The Tower of London is in the care of Historic Royal Palaces.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. All quotes from John Feltham’s The Picture of London for 1809 (1809).

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph and Combe, William, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 3 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809)

Humphrys, Julian, The private life of palaces (Historic Royal Palaces, 2006)

Thornbury, Walter, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London)