|

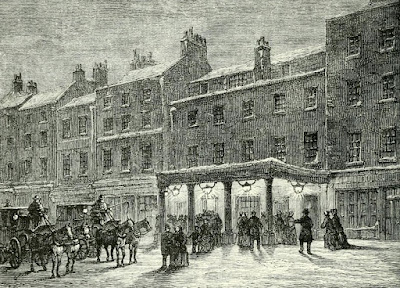

| Old Haymarket Theatre from Old and New London (1873) |

In Georgian London, it was necessary to have a licence in order to perform plays. In 1766, the Theatre Royal, Haymarket, was granted a royal patent, allowing it to put on plays, but only during the summer season. There were only two theatres licensed to put on plays during the winter: The Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, and the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden.

The First Haymarket Theatre

The first theatre in the Haymarket was built by John Potter in 1720 and was known as The First Haymarket Theatre or Little Theatre. The Licensing Act of 1737 meant that theatre companies needed a licence or patent in order to perform plays. The Haymarket had no such licence and was forced to operate under temporary licences or by trying to circumvent the law by putting on a concert with a ‘free’ play afterwards.

|

| Interior of the Little Theatre, Haymarket, from the Complete Works of Henry Fielding (1902) |

The Theatre Royal, Haymarket

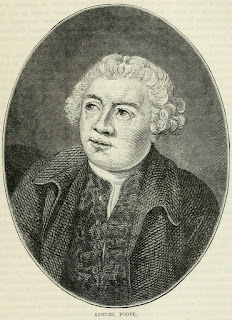

From 1746, comic actor and satirical playwright Samuel Foote sporadically rented the Haymarket Theatre. In 1766, whilst the guest of his noble patrons, the Earl and Countess of Mexborough, Foote was goaded into riding a rather lively horse belonging to George III’s brother, Edward, Duke of York. The horse threw him and Foote broke his leg so badly that it had to be amputated. Undeterred, Foote continued to act with a wooden leg:

Strange as it may appear, with the aid of a cork leg he performed his former characters with no less agility and spirit than before, and continued by his laughable performances to draw together crowded houses.1

The accident brought about a change in fortunes for the Haymarket Theatre. Foote requested a royal patent from the Duke of York and on 5 July 1766, a limited patent was granted, for the duration of Foote’s life. The Haymarket Theatre was permitted to show plays during the summer, between 10 May and 15 September.

Foote purchased the theatre outright and immediately set about enlarging it, adding an upper gallery. It reopened as the Theatre Royal on 14 May 1767.

|

| Samuel Foote from Old and New London (1873) |

George Colman the elder

Playwright George Colman bought the theatre in 1777, but the patent expired on Foote’s death in the same year, forcing him to apply annually for a licence for the summer season. The Haymarket flourished under his management and he amassed a considerable fortune, only to discover that his banker had embezzled it. His son, also called George Colman, gradually took over the management from 1785 due to his father’s ill health.

Sheridan’s Drury Lane Theatre company performed at the Haymarket during the winter season of 1793-4 whilst his theatre was being rebuilt.

Death at the theatre

During this time, a dreadful tragedy took place. On 3 February 1794, George III and Queen Charlotte attended the Haymarket Theatre for the first time that season, and the royal command performance attracted vast numbers of people. The crowds were so huge that when the door was opened, those in the front of the queue were pushed down the stairs leading to the pit. More than 70 people fell and at least 15 people were fatally crushed to death or suffocated.

During this time, a dreadful tragedy took place. On 3 February 1794, George III and Queen Charlotte attended the Haymarket Theatre for the first time that season, and the royal command performance attracted vast numbers of people. The crowds were so huge that when the door was opened, those in the front of the queue were pushed down the stairs leading to the pit. More than 70 people fell and at least 15 people were fatally crushed to death or suffocated.

George Colman the younger

George Colman the younger inherited the theatre on his father’s death in 1794, along with massive debts. Although a successful playwright, he was forced to mortgage the business to repay his father’s debts and finally, in 1805, to sell shares in the theatre. In 1806, he was arrested for debt but he continued to manage the theatre from the King’s Bench Prison until he was discharged in 1817.

The shareholders included his argumentative brother-in-law, David Morris, who involved Colman in such lengthy litigation which forced the theatre to stay closed during the summer of 1813.

|

| King's Bench Prison from The Microcosm of London Vol 2 (1808-10) |

According to The Picture of London for 1809, the season at the Haymarket Theatre ran from 15 May to 15 September. It wrote of the Haymarket Theatre:

This theatre, though not so elegant and spacious as either of the winter houses, is fitted up in a neat and tasteful style, and is capable of containing a numerous audience.2

This house contained three tiers of boxes, a pit, and two galleries.

The Haymarket Theatre presented plays and English operas. The Picture of London for 1813 stated that the Haymarket was putting on plays and farces rather than operas.

Visiting the theatre

The doors opened at six o'clock, and the performance began at seven. Unlike the winter theatres, there was no half-price entry at the Haymarket part the way through the evening’s performance.

The post-Regency years

After his release from prison, Colman sold the remainder of his interest in the theatre. Under the management of David Morris, the theatre was completely rebuilt in 1820, in a slightly different place, according to the design of architect John Nash. It reopened on 4 July 1821 with a production of Sheridan’s The Rivals.

Old and New London wrote:

|

| New Haymarket Theatre from Shakespere to Sheridan by A Thaler (1922) |

The front is of stone, and is about sixty feet in length, and nearly fifty in height. The entrance is through a handsome portico, the entablature and pediment being supported by six columns of the Corinthian order; above are circular windows connected by sculpture of an ornamental character. Under the portico are five doors, leading respectively to the boxes, pit, galleries, and box-office. The shape of the interior differs from that of every other theatre in London, being nearly a square, with the side facing the stage very slightly curved. The expense of the new building was about £20,000. It is a remarkably neat and pretty house, having two tiers of boxes, besides other half-tiers parallel with the lower gallery, and will seat about 1,500 persons with comfort.3

|

| Haymarket Theatre from Leigh's New Picture of London (1827) |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 4.

(2) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809).

(3) From Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 4.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph, and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 2 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Baldwin, Olive and Wilson, Thelma, Colman, George, the elder (bap1732, d1794), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 12 April 2017)

Birling, William J, Colman, George, the younger (1762-1836), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 12 April 2017)

Dircks, Phyllils T, Foote, Samuel (bap 1721, d 1777), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Sept 2015, accessed 12 April 2017)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 4

(1) From Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 4.

(2) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809).

(3) From Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 4.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph, and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 2 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Baldwin, Olive and Wilson, Thelma, Colman, George, the elder (bap1732, d1794), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 12 April 2017)

Birling, William J, Colman, George, the younger (1762-1836), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 12 April 2017)

Dircks, Phyllils T, Foote, Samuel (bap 1721, d 1777), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Sept 2015, accessed 12 April 2017)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 4

Fascinating and most interesting research. Very useful for me as a historical author. Thank you.

ReplyDeleteFascinating stuff, though I must say that fire, debt and disaster seems to have been an occupation hazard for most of the theatre managers! Samuel Foote was a very courageous man.

ReplyDeleteEnjoyed this post. It's astonishing how many theatre managers had to cope with fire, debt and disaster at this period. It was almost an occupational hazard.

ReplyDeleteWilliam James Meadows performed in Love in a village and so did other ancestors of mine. Very awesome history theatre is beautiful

ReplyDelete