|

| Gentleman's full dress from Ackermann's Repository (1810) |

This is what I found fascinating. Hannah More painted a series of character portraits based on her observations, giving the modern-day reader an insight into how people were living their lives in the early 1800s. In particular, More looked at the subject of religion and how people’s beliefs were worked out in their day-to-day lives – or not!

It seems incredible to us that, early on in the book, More felt it was necessary to make an apology, suggesting that ‘the religious may throw it aside as frivolous’.2 I guess it might have seemed frivolous compared to a book of sermons!

It is much easier to understand why she also pre-empted the criticism of the novel reader whom she thought might ‘reject it as dull’. The book is full of good conversation and good advice but, as I’ve already mentioned, very little action takes place.

That said, the book was very popular in its time, and others tried to mimic More’s success with titles such as Nubilia in Search of a Husband. The popularity of Coelebs and the charitable character of its heroine, Lucilla Stanley, helped to make it fashionable to care for the poor.

A summary of the story

|

| Hannah More from Memoirs of the life and correspondence of Mrs Hannah More by William Roberts (1835) |

What Charles is looking for in a wife

The hero, Charles, lives at the Priory in Westmoreland, where he has been living a retired life, attending his father through his final illness and then supporting his mother until her death. He is now eager to find a wife. His own ideas of the ideal woman are based on Eve in Milton’s Paradise Lost.

Before his death, his father had counselled him to choose a wife who was informed, cultivated and refined.

The exhibiting, the displaying wife may entertain your company, but it is only the informed, the refined, the cultivated woman who can entertain yourself.

You will want a companion: an artist you may hire.

He had also urged him not to choose a wife until he had visited his old friend Mr Stanley, who lived at Stanley Grove in Hampshire.

His mother had also given him advice, saying that many unobjectionable characters were not designed to give rational happiness in marriage. She advised him:

It is not unreasonable to expect consistency.

Charles spells out what he is looking for in a wife:

I do not want a Helen, a Saint Cecilia, or a Madame Dacier; yet she must be elegant, or I should not love her; sensible, or I should not respect her; well-informed, or she could not educate my children; well-bred, or she could not entertain my friends; consistent, or I should offend the shade of my mother; pious or I should not be happy with her, because the prime comfort in a companion for life is the delightful hope that she will be a companion for eternity.

The search begins

Charles visits some of the local families before heading for London on his way to Mr Stanley’s house. Everywhere he goes, he meets potential brides and becomes aware of numerous inconsistencies in people’s characters.

Charles finds Mr Stanley as amiable as he had hoped. Mr Stanley has the ability to say the right thing at the right time and to turn discussions on non-religious subjects into useful instruction. Mrs Stanley has the ability to bring out the best in people. She laments the damage done by novels by establishing the omnipotence of love, encouraging young readers to unresistingly submit to a feeling.

Lucilla Stanley

Mr and Mrs Stanley have a family of daughters: 18-year-old Lucilla, 15-year-old Phoebe and several younger girls. They lost their only son some years before. Lucilla is everything that Charles wants in a wife. She is intelligent, kind, truly good and charitable, and modest with it. She has been doing the housekeeping since she was 16 and sets aside a day each week to serve the poor and visits them two evenings a week in their homes. She and her sisters have built up a large stock of clothing that they give out at Christmas.

|

| Morning dress from Ackermann's Repository (1811) |

The Stanleys believe too much time is spent on music for exhibition rather than developing conversation, and so Lucilla is cultured rather than accomplished.

The excellence of musical performance is a decorated screen, behind which all defects in domestic knowledge, in taste, judgement, and literature, and the talents which make an elegant companion, are creditably concealed.

|

| Fashionable afternoon and morning dress from Lady's Magazine (1807) |

Lucilla is not without other suitors and Charles is jealous of Lord Staunton. Lucilla has rejected him once because of his loose principles, but he has not taken ‘no’ for an answer. He has told her that she can reform him. Lucilla refuses to accept a man with promises of reform because if he failed to reform, ‘it would be too late to repent of my folly, after my presumption had incurred its just punishment.’ Charles fears that Lord Staunton will genuinely reform and be accepted.

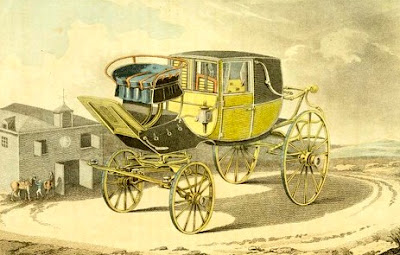

Charles’s new carriage arrives and Lucilla’s youngest sister, Celia, is afraid that Charles is going to go home. Charles invites her to go with him. She innocently says that she will go to the Priory with him if Lucilla will go too, making her poor sister blush. Despite the promised month not being up, Charles proposes and Lucilla accepts him.

|

| Elliott's patent eccentric laundaulet or chariot from Ackermann's Repository (1809) |

A bevy of little stories

The people that Charles meets along his journey each have a little story of their own, containing examples of good behaviour and bad, and how people either suffered the consequences of their folly or profited from adopting better habits. Here is a summary of some – but by no means all – of these stories.

Sir John and Lady Belfield were religious at heart but it did not affect the way they behaved. Sir John had found that too much religion could damage a man’s reputation. Lady Belfield was over indulgent towards her children. After visiting Stanley Grove and talking with and observing Mr and Mrs Stanley and their family, they made the decision to reduce the time they stayed in London over the winter and instruct their children better.

Mr and Mrs Carlton started off as an unmatched couple, obliged to marry to keep property within the family. Mr Carlton was irreligious and unkind whilst Mrs Carlton was devoutly religious. Although she had been in love with someone else, she lived out her faith in front of her husband, never allowing herself to criticise him and excelling in her domestic duties. Her faithful witness eventually won over her husband.

Ned Tyrrel had been at college with Mr Stanley but turned very dissolute. Later he reformed, but became addicted to ambition and then money, and he adopted some very extreme ideas about religion based on forgiveness without reform. Only when he becomes ill and is about to die does he suddenly realise how hollow his religion is.

Lady Melbury is a very popular lady in London’s high society. She is very charitable, but also very profligate. This comes to a head when she proposes to give a poor girl in a flower shop who is caring for her sick mother her custom but then realises it is her own failure to meet her debts that caused the poverty of the family in the first place. She claims she will give up gambling and never get in debt again, but finds it hard to resist the influence of others. It is only when she is left alone to think about her faults that the change really occurs. She saves enough money to pay off her debt by retiring to the country and cancelling a big entertainment she had planned. She resolves to live a retired life to avoid the contaminating influence of London society.

Lady Denham gives the appearance of religiosity but has no real feeling. She blames her inability to support charity on taxes and yet finds it possible to give generously to her favourite opera singer Signor Squallini’s benefit concert. With her, music is supreme. She gets her come-uppance when her daughter elopes with Squallini.

|

| Opera dress from Ackermann's Repository (1809) |

Lady Aston had lived a retired life in the country ever since her husband’s death. She saw it as a duty to mourn him and would not let her daughters do anything. As a result, they were wasting their time. Mr Stanley encouraged the girls to set up a school for the poor and read with the curate. The whole family became much happier.

Mr and Mrs Ranby had a reputation for being pious, but their religion consisted of a ‘disproportionate zeal for a very few doctrines’. Mrs Ranby was coarse and censorious and gave no religious instruction to her daughters who wasted their time. She thought it was enough to pray for them! Mrs Ranby did not see the relevance of religion to everyday matters, such as governing her temper.

Mr Stanhope was drawn in by beauty to an unequal marriage. His wife held his books in great aversion and was ill-informed and bad tempered. An example of a marriage where two people were ‘joined not matched’.

To protect each other from worry, Mr and Mrs Hamilton had tried to conceal their illnesses from each other for the first seven years of their marriage. They came to realise that concealment was dangerous even when the intentions were good.

Unreserved communication is the lawful commerce of conjugal affection, and all concealment is contraband.

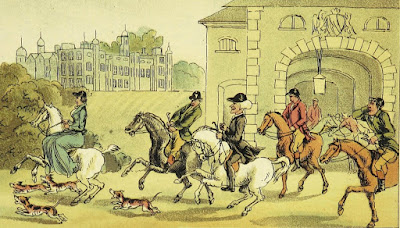

Miss Sparkes, a single lady of 45 who was neither poor nor ugly, was very masculine in her habits – she was a politician, a huntsman, a farrier and a coachman. She believed that clever men married stupid women because they feared a rival, and that a woman who excelled in domesticity must be downtrodden.

|

| A noble hunting party by T Rowlandson from Dr Syntax's Three Tours by William Combe (1868) |

Mr Flam had good deeds without religion. Dr Barlow, the minister, warns him that he is as much at risk as Mr Tyrrel and his sham religion. However, Mr Flam is young and thinks he has plenty of time ahead of him to sort things out.

Notes

(1) Sometimes written as Cœlebs in Search of a Wife.

(2) All quotes taken from Cœlebs in Search of a Wife by Hannah More, (New York, 1859, edition).

(2) All quotes taken from Cœlebs in Search of a Wife by Hannah More, (New York, 1859, edition).

Jane Austen was ticked off with the title. She didn't realize that Coelebs was Latin for bachelor.

ReplyDeleteThe book is like Grandison -- in that he, too, was seeking a wife.

Thanks for the enlightenment! I never thought of translating Coelebs and struggled to understand the title. Now it makes perfect sense.

DeleteI really enjoyed this post. It reminded me of 'A Correspondence between a Mother and Her Daughter' by Jane Taylor, published in 1817 (I have a copy) which doesn't really have a plot - it's more a series of incidents in which the daughter, who is at school, learns how to detect falseness, cope with jealousy, choose the right path, which may be the more difficult, and so on.

ReplyDeleteI loved Miss Sparkes! She's the woman I'm rooting for. She deserves a story of her own.

Sounds very similar in spirit to the book you mention. Enjoyable from a historial point of view, but not much plot!

DeleteFascinating. You've made me want to read this book!

ReplyDeleteI hope you enjoy it.

DeleteThank you - I don't know that I shall ever read this, but I am pleased to know more about it! I suspect my novel reading habits would be considered too frivolous by the upright Stanleys!

ReplyDeleteI'm glad you found the post helpful. Although fictional, it felt more like historical research than novel reading!

Delete