- The Phantasmagoria

The Picture of London for 1802 stated:

The Phantasmagoria; at the Lyceum.

This exhibition consists simply of a new application of the common magic lanthorn; the images, instead of being thrown, in the usual way, upon a white sheet, are thrown upon a transparent scene, which is hung between the lanthorn and the spectator. The images are consequently seen through the scene, are more distinct, and the effect to the spectator is greatly improved. To prevent the passage of extraneous light, the sliders are painted black, except on the part on which the figures are painted. The motion of the eyes and mouth, in some figures, is produced by double sliders.

The admittance is four shillings to the boxes, and two shillings to the pit. Some weak imitations have been exhibited in other parts of the town.4

- A second phantasmagoria was also advertised in the same year:

The Egyptiana, and Phantasmagoria; at the Lyceum in the Strand.

This consists of various scenery, drawn and designed from nature in Egypt; and, by way of relief, there is an intermixture of recitations. The plan of exhibiting the scenery of foreign countries upon a. large scale, deserves encouragement; and, it is to be hoped, that it will in due time be extended to other countries besides Egypt: and thus amusement be made a vehicle of historical knowledge. Phantasmagoria are added.4

- Madame Tussaud’s waxworks

Philipstal and his phantasmagoria have long been forgotten, but his business partner at the time has not. That partner was Madame Tussaud, who travelled to England with Philipstal in 1802 to exhibit her waxworks at the Lyceum. These were not the first waxworks to go on display at the Lyceum. For several seasons in the 1780s, Mr Silvester had exhibited his waxworks there.

|

Madame Tussaud from Madame Tussaud's

Memoirs and Reminiscences of France (1838) |

It is interesting to note that the Picture of London for 1802 did not include any reference to Madame Tussaud’s waxworks. I discovered when researching Madame Tussaud’s story for What Regency Women Did For Us that Philipstal was responsible for all the advertising for their exhibitions. Madame Tussaud complained that Philipstal did not mention her on the advertisements and I wonder whether that might account for why her exhibition is not mentioned in the Picture Of London.

- Mr Porter’s pictures

Robert Kerr Porter exhibited several large paintings over a number of seasons at the Lyceum, including The Battle of Alexandria in 1802 and The Storming of Seringapatam in 1805. The Picture of London for 1802 advertised the Picture of the Battle of Alexandria:

Mr Porter, at the Lyceum, in the Strand, has lately opened an exhibition of a large picture, representing the celebrated battle between the English and French armies, on the 23d of March, 1801, before Alexandria, in Egypt. The subject is connected with the national vanity, and will, therefore, no doubt, draw large assemblages of spectators. The admission is one shilling.4

Theatrical entertainments

Although the Lyceum did not have a licence for theatrical performances, it was able to show other entertainments. These included:

- Theatrical imitations by George Saville Carey called The Diversions of an Evening

- Mr Dibdin’s New Entertainment.

Charles Dibdin was a famous songwriter and his show ran for 108 nights at the Lyceum in the autumn of 1790 alone.

- Astley’s Circus

When Astley’s Amphitheatre at Westminster Bridge burn down in 1794, Philip Astley transferred part of his circus to the Lyceum whilst it was rebuilt.

- Boxing in Mendoza’s Academy

Champion boxer Daniel Mendoza opened a boxing academy in the Lyceum in 1789. Spectators could watch a fight between one and three o’clock and the prices were 1s 6d for boxes and 1s for the gallery. The proprietor of the Lyceum advertised the academy saying:

As Daniel Mendoza has divested his Exhibition of every degree of Brutality and rendered the Art of Boxing equally neat with Fencing, he thinks it necessary to mention that his Plan does not exclude the Company of Ladies.5

|

Polite Amusement or an Exhibition of Brute Beasts at the Lyceum

from The Lyceum and Henry Irvine by A Brereton (1903) |

- The Loyal Theatre of Mirth

In 1805, the Lyceum put on a Grand Spectacle called The Female Hussar.

- The emperor of all the conjurors

The Picture of London for 1809 stated that:

A licence has likewise been obtained for a theatre in Catherine-street for conjurors; and another at the Lyceum, in the Strand, for the same purpose. The one is conducted by Mr. Ingleby, who has assumed the title of king of the conjurors; the other by Mr M, who stiles himself emperor of all the conjurors.6

Private Theatricals

The theatre was also used for private theatricals. The Picture of London for 1806 stated:

Private Theatres.

Upon a small scale may be mentioned those of Tottenham-court-road, Berwick-street, and the Lyceum in the Strand; in the two latter of which not less than ten different companies perform. Tickets are delivered gratis by the performers to their friends, and are procured, in their respective neighbourhoods, without much difficulty.7

In 1809, Samuel Arnold applied for a licence for the Lyceum, but was only granted a licence from 3 June to 3 October for ‘musical works of a light order’.8

However, when

the Drury Lane Theatre burnt down on 24 February 1809, the company performed at the Lyceum under their own licence from 11 April 1809. It continued to perform there until the new Drury Lane Theatre opened in October 1812. According to Austin Brereton, Arnold did not fare badly by this arrangement. He received £900 a year and a third of the profit for the three seasons that the Drury Lane company performed at the Lyceum.

English Opera

During the summer, the Lyceum was used mostly for operas, burlettas and other musical pieces. It was known by different names at this time – sometimes the Theatre Royal, Lyceum, and sometimes as the Theatre Royal English Opera. The Picture of London for 1813 stated:

Mr. Arnold, author of a variety of dramatic pieces of superior merit, and son of Dr Arnold, of musical celebrity, has tried, with deserved success, the experiment of an English opera during the two last seasons at the Lyceum. We can assert, that it has afforded the highest gratification, and is one of the most elegant entertainments to an English ear which the metropolis affords. An English school of harmony, like an English school of painting, has been thought a solecism by some conceited critics, but many of the performances of the Lyceum have proved the falsehood of those observations, as much as the exhibitions of English painters have proved the error of foreign critics.

The English Opera is under the joint management of Messrs. Arnold and Raymond, and its whole conduct evinces superior taste and great public spirit.

The prices of admission are the same as those of the Drury-lane Company at the same house.9

These prices were: 7s to the boxes; 3s 6d to the pit and 2s and 1s to the galleries.

Samuel Arnold’s new theatre (1816-1830)

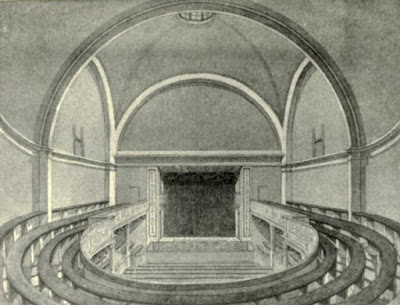

The Lyceum was rebuilt by Samuel Arnold in 1816 to a design by playwright and theatre architect Samuel Beazley (1786-1851) at a cost of £80,000. It was known as the English Opera House.

It opened on 17 June 1816 with a performance of Arnold’s opera Up All Night.

“The front is in line with the houses on the north side of the Strand. It has a stone portico, supported by eight Ionic columns, between which” (in 1825) “suspended large gas lanterns. The columns are connected by an inclosure of fancy iron-work, and support a stone balcony, with rounded balustrades; in the centre of which is a large square tablet, in which is engraved the word ‘Lyceum’. Above this, are three tiers of windows (three in a tier) surmounted by a neat pediment; and the second and third tiers are divided by bands, on the upper of which appears ‘Theatre Royal’ and on the lower ‘Lyceum Tavern’. The lower part of the building, under the portico, contains two admission doors to the boxes and pit, and one window. The entrances to the two galleries, and another to the pit, are in a court communicating with the Strand and with Exeter Street; and in the latter street is the stage-door. A long passage and a staircase lead to the boxes, whence there is an entrance to a long room, called The Shrubbery, from a large quantity of green and flowering shrubs being placed in the centre and corners of the room, rising pyramidically to the ceiling.”10

The auditorium was in the shape of a lyre. There were two tiers of twenty boxes and four ‘pigeon-holes’ or small boxes on each side of the stage.

On 6 August 1817, the Lyceum introduced gas light on the stage and later that year, it lit the auditorium by gas as well.

|

Lyceum Theatre, Box Entrance (in the Strand), 1825

from The Lyceum and Henry Irvine by A Brereton (1903) |

Mixed fortunes

The Lyceum struggled to find steady success. Some entertainments drew in the crowds, but in 1817, the Lyceum was putting on two shows a night, at 6pm and 9.30pm, in order to increase its profitability. Some of the more notable entertainments held at the Lyceum during this period were:

- A Grand Venetian Festival and Masqued Ball on 17 February 1817

Gentlemen’s tickets were priced at £1 11s 6d and ladies’ tickets at £1 1s 0d, with supper tickets, including wines 10s 6d each.

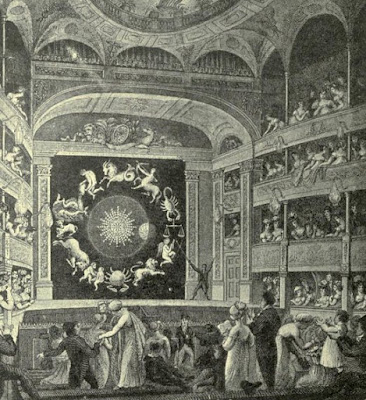

- Walker’s Eidouranian

A scientific and astronomical lecture, featured in the print at the top of this post.

- The Gathering of the Clans

A Scottish entertainment including highland dances and reels and an exhibition of broad sword playing. It was first shown on 10 February 1818 under the express patronage of the Duke of Sussex and several highland noblemen.

- Charles Mathew’s one-man shows

On 2 April 1818, Charles Mathews announced he was ‘At Home at the Theatre Royal English Opera House’ with Mail Coach Adventures which ran, very successfully, until 17 June. He returned in subsequent seasons with different shows including A Trip to Paris and Country Cousins and the Sights of London.

|

| Charles Mathews from The Lyceum and Henry Irvine by A Brereton (1903) |

- The Vampire

A melodrama, successfully performed from 1820.

- Carnivals

These were fancy dress balls held at the Lyceum in 1821 for the price of 1 guinea admission. Supper tickets were an additional ½ guinea and guests were advised that private rooms could be engaged in advance and that there would be plenty of police around to ensure security.

The later years

On 16 February 1830, in the early hours of the morning following the first performance of Les Trois Quartiers, the English Opera House was completely destroyed by fire. The theatre was immediately rebuilt to a design by Samuel Beazley, with its main entrance now onto Wellington Street rather than the Strand. It opened as the new Theatre Royal Lyceum and English Opera House on 14 July 1834.

The Lyceum was rebuilt in 1904 by Bertie Crewe, but retained Beazley’s façade and grand portico. The Lyceum Theatre still operates as a theatre in the West End of London today. You can find out about the theatre today on

the Lyceum Theatre website.

|

| Lyceum Theatre (2015) |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From Ackermann, Rudolph, and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 1 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

(2) From Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 3

(3) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1805 (1805)

(4) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1802 (1802)

(5) From Brereton, Austin, The Lyceum and Henry Irving (1903)

(6) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809)

(7) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1806 (1806)

(8) From Brereton, Austin, The Lyceum and Henry Irving (1903)

(9) From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

(10) From Brereton, Austin, The Lyceum and Henry Irving (1903)

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph, and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature Volume 1 (Rudolph Ackermann 1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Brereton, Austin, The Lyceum and Henry Irving (1903)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1802 (1802)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1805 (1805)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1806 (1806)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1807 (1807)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1809 (1809)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (Jan 1810)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 3

Lyceum Theatre website

Photographs © RegencyHistory.net