Kensington Gardens were originally part of Hyde Park. They were created when, in 1689, William and Mary bought Nottingham House and made it their London residence, renaming it Kensington Palace. The palace gardens were formed out of the western edge of Hyde Park and consisted of a mere 26 acres which Mary planted with formal flower beds and ‘closely-cropped yews, and prim holly hedges’.1

Queen Anne enlarged the gardens by another 30 acres and created an English garden. She also added the orangery and built a hermitage in the gardens.

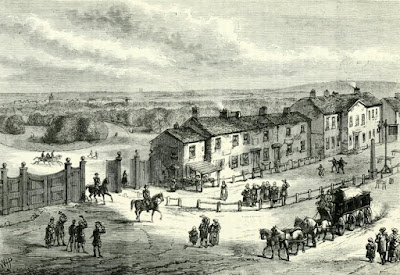

|

| Map of Kensington Gardens in 1764 from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

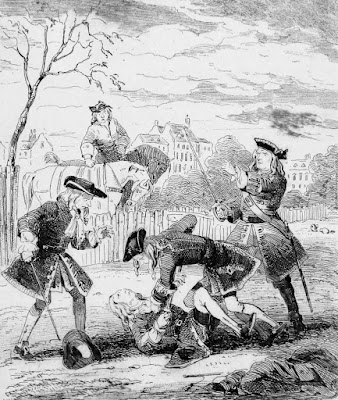

|

| The round pond, Kensington Gardens from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

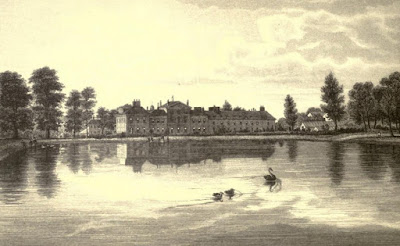

|

| Queen Caroline's Temple, Kensington Gardens |

Kensington Gardens were separated from Hyde Park by a long ditch, known as a ha-ha, which divided the two parks without interrupting the view of the landscape with a high wall or fence. Ha-has were widely copied around the country.

According to Old and New London, ‘the principal embellishments were entrusted to Mr Kent, and subsequently carried out by a gentleman well known by the familiar appellation of "Capability" Brown.’2

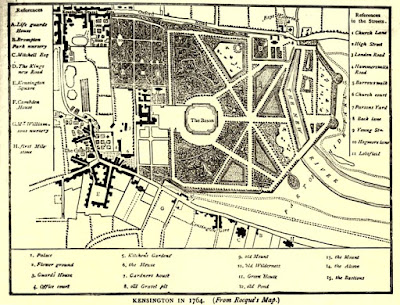

|

| Kensington Palace, Kensington Gardens from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

These grounds appear to have been a favourite resort of the high-born and fair, as far back as the reign of George II. though they were then only open to the public on Saturdays, when the court was at Richmond.3

Queen Caroline’s gardens were opened to the public on Saturdays when the king and his court were at Richmond, but presumably only those of the highest classes of society came, as visitors were required to wear full dress.

Kensington Gardens in the reign of George III

|

| Flower walks, Kensington Gardens from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

An article in the Monthly Register for September 1802 remarked:

All the views from the south and east facades of the edifice suffer from the absurdity of the early inspectors of these grounds. The three vistas opening from the latter, without a single wave in the outline, without a clump or a few insulated trees to soften the glare of the champagne, or diminish the oppressive weight of the incumbent grove, are among the greatest deformities. The most exquisite view in the Gardens is near the north-east angle; at the ingress of the Serpentine river, which takes an easy wind towards the park, and is ornamented on either side by sloping banks, with scenery of a different character. To the left the wood presses boldly on the water, whose polished bosom seems timidly to recede from the dark intruder; to the right, a few truant foresters interrupt the uniformity of the parent grove, which rises at some distance on the more elevated part of the shore; and through the boles of the trees are discovered minute tracts of landscape, in which the eye of taste can observe sufficient variety of light and shade of vegetable and animal life to gratify the imagination, and disappoint the torpor, which the more sombre scenery to the east is accustomed to invite.4

|

| Kensington Gardens from Views in Kensington Gardens by J Sargeant (1831) |

These gardens join the western extremity of Hyde Park, to which they give a very fine effect; as the park on that side appears, from the noble foliage of the gardens, to terminate in an extensive wood. The disposition of the grounds, though far from the present refinement in gardening, abounds too much with strait walks and lines, yet it possesses great beauty and grandeur. These gardens were improved by the celebrated Brown.

Near the palace, within the pleasure-grounds, is a very noble green-house, and adjoining are excellent kitchen and fruit gardens.5

|

| Kensington Palace from Kensington Gardens from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

Few spots have attained so universal, and deserved a reputation as these delightful grounds. Their convenient situation, immediately on the western border of the metropolis, united to the beauty and sequestered nature of the scenery, have made them the favourite promenade, and resort, during favourable weather, of the high born and fair, as well as the more humble classes of our ‘modern Babylon’. Thus, affording so pleasing, and healthful a source of recreation to the inhabitants of a great capital, we can scarcely regret that the palace has so long been abandoned by the court.6

The fashionable promenade

|

| Kensington Gardens from Views in Kensington Gardens by J Sargeant (1831) |

A noble walk, stretching from north to south, in Kensington Gardens, at the eastern boundary, with its gay company, completes this interesting scene. Numbers of people of fashion, mingled with a great multitude of well-dressed persons of various ranks, crowd the walk for many ours together.7

|

| Kensington Gardens from Views in Kensington Gardens by J Sargeant (1831) |

At Kensington-gardens you are obliged to leave your horse or carriage standing at the gate. Walking through its shady alleys I observed with pleasure that the fashionable ladies pay, in regard to dress, a just tribute to our fair countrywomen. Judging from the costumes of the ladies, you might sometimes fancy yourself walking under the chestnut trees of the Tuileries.8

The Picture of London for 1813 stated:

Kensington Gardens are open to the public, only from spring till autumn; and from eight in the morning till eight at night. There are four gates belonging to these gardens: two that open into Hyde Park; one opening into the Uxbridge-road; and another opening into a road belonging to the king, and leading from the palace into Kensington. The last of these gates, called the Avenue-gate, is open till nine at night. No servant in livery, nor women with pattens, nor persons carrying bundles, are admitted into the gardens. Dogs are excluded.9

|

| Kensington Palace from the fashionable walk in Kensington Gardens from Views in Kensington Gardens by J Sargeant (1831) |

In a letter to her sister Cassandra dated 25 April 1811, Jane Austen wrote:

I had a pleasant walk in Kensington Gardens on Sunday with Henry, Mr Smith, and Mr Tilson; everything was fresh and beautiful.10

The Picture of London for 1810 stated:

It is necessary to apprize strangers, that it is not always safe to be in Hyde Park, or Kensington Gardens, after dark. These places being so extensive, opportunities of robbery, or ill-usage, are easily given; and it is impossible to shut out public robbers, or other ill-disposed persons.11

Kensington Gardens today

When Queen Victoria established her court at Buckingham Palace, Kensington Gardens went out of fashion. The ha-ha was largely filled in and Kensington Gardens were separated from Hyde Park by the West Carriage Drive instead.

The gardens now contains several statues and memorials including:

|

| Statue of Queen Victoria in Kensington Gardens |

• A statue of Queen Victoria, sculpted by her daughter Princess Louise, which was erected outside Kensington Palace to celebrate her golden jubilee.

• The Albert Memorial, in remembrance of Prince Albert, Queen Victoria’s husband.

• Peter Pan.

• Diana, Princess of Wales, Memorial Playground.

Kensington Gardens are open to the public throughout the year, from 6 am to dusk. More information on the Royal Parks website.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 5.

(2) Ibid.

(3) Sargeant, John, Views in Kensington Gardens (1831).

(4) Walford op cit.

(5) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

(6) Sargeant op cit.

(7) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813).

(8) Pichot, Amédée, Historical and Literary Tour of a Foreigner in England and Scotland (1825) Vol 1

(9) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813).

(10) Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892).

(11) Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810).

Sources

Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892)

Crosby, B, A View of London; or the Stranger's Guide through the British Metropolis (Printed for B Crosby, London, 1803-4)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1810 (1810)

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1813 (1813)

Phillips, Richard, Modern London; being the history and present state of the British Metropolis (1804)

Pichot, Amédée, Historical and Literary Tour of a Foreigner in England and Scotland (1825) Vol 1

Sargeant, John, Views in Kensington Gardens (1831)

Walford, Edward, Old and New London: A narrative of its history, its people, and its places (Cassell, Petter & Galpin, 1873, London) Vol 5

Photos © regencyhistory.net