I am delighted to welcome author Julie Tetel Andresen to the Regency History blog today with a guest post on policing Georgian London and the Bow Street Runners.

|

| Bow Street from The Microcosm of London Vol 1 by R Ackermann and WH Pyne (1808) |

In the early 1750s, magistrate and novelist Sir Henry Fielding persuaded the government to provide funds to hire men who would have the capacity to track down the highwaymen and footpads who were terrorizing the roads in and around London. He lived at Number 4 Bow Street, Covent Garden. A few months after receiving the funds, Henry Fielding died, leaving the Bow Street residence to John Fielding, his younger half-brother. Although John had been blind since the age of nineteen, he turned out to be the most imaginative magistrate of the eighteenth century, and created a force of policemen who were popularly called Bow Street Runners.

Since the thirteenth century, London had unpaid night watchmen. However, a troubling spike in crime occurred in the late seventeenth century, likely caused by the demobilization of armed forces after William III won the war for the throne in 1689. In response to this increase in violence, two things had come about by the middle of the eighteenth century: first, the lighting of the streets had been improved; and, second, the night watchmen had become a paid force. They had established beats at set times, called out the time throughout the night, and made an arrest if they happened upon a crime. However, they were not expected to search out offenders.

Parish Constables

The parish constables were largely private citizens who served for part of a year as their civic duty. They were expected to clear the streets of vagrants and prostitutes, and they could arrest petty criminals if, like the night watchmen, they happened upon them. They were also supposed to keep crowds under control on days of celebration or when crowds assembled for unlawful purposes. The constables were under no obligation to do anything beyond the boundaries of their jurisdiction, and they were not expected to investigate crimes or find criminals.

The parish constables were largely private citizens who served for part of a year as their civic duty. They were expected to clear the streets of vagrants and prostitutes, and they could arrest petty criminals if, like the night watchmen, they happened upon them. They were also supposed to keep crowds under control on days of celebration or when crowds assembled for unlawful purposes. The constables were under no obligation to do anything beyond the boundaries of their jurisdiction, and they were not expected to investigate crimes or find criminals.

Thief-takers

Occasionally a magistrate would take an interest in a particular case and follow through on it. However, it was mostly left to the victim to find the perpetrator or to pay someone to do so. In the early eighteenth century, one could hire a private ‘thief-taker’, as they were called. The men Sir John Fielding hired became the first professional public thief-takers, although the term they came to be known by, namely Runners, was surely derogatory since it associated them with the bailiffs who arrested debtors or escorted men to jail.

Occasionally a magistrate would take an interest in a particular case and follow through on it. However, it was mostly left to the victim to find the perpetrator or to pay someone to do so. In the early eighteenth century, one could hire a private ‘thief-taker’, as they were called. The men Sir John Fielding hired became the first professional public thief-takers, although the term they came to be known by, namely Runners, was surely derogatory since it associated them with the bailiffs who arrested debtors or escorted men to jail.

Sir John Fielding and the Bow Street Runners

The Runners, whom Sir John often recruited from the ranks of ex-constables, helped victims at no cost, followed investigations wherever they went, and had the authority to arrest the criminals anywhere. By bringing to justice those guilty of highway robbery and murder, and by increasing the geographical range of pursuit, the Runners formed the very beginnings of a national police force.

|

| Sir John Fielding by Nathaniel Hone Oil on canvas (1762) NPG 3834 (1) |

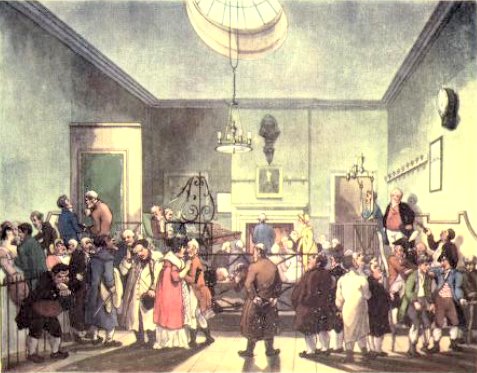

Since 1748, Sir Henry Fielding had made his house on Bow Street the centre of his work. When Sir John took over in 1754, he made it a centre for information gathering, which went beyond the clerical requirements of ordinary magistrates at the time. He hired extra staff to collect information about crimes and criminals and believed informers should be paid. He also used advertising as fundamental to his policing strategy. For crimes of theft, he sent information to appear in the next day’s newspapers and had handbills printed and distributed to pawnbrokers and other likely places, under the belief that rapid dispersal of information was necessary if goods were going to be found and the thieves arrested. The office seemed to have been open for business for long hours most days of the week, and people came to assume they could go to Bow Street at any time of the day, and well into the evening, to see a magistrate (or at least someone who could take and perhaps act on their complaint).

On occasion, a Runner might take an alleged criminal to the Brown Bear, a pub across the street from the office, which served as a temporary lock-up and a place where suspects could be interrogated before being taken before the magistrate. Conveniently, Sir John often ate at the Brown Bear, and so was on hand if fresh business came up during his meal.

|

| The Brown Bear from Chronicles of Bow Street Police-Office by Percy Fitzgerald (1888) |

The effectiveness of the Runners can be illustrated with an example. In 1767, John Griffiths and three other men were returning to London by coach when a gang of armed men stopped them and demanded their money. One of the men in the coach jumped out in an effort to escape and was knocked down and badly beaten. Griffiths refused to give up his purse and was shot dead. The other two did not resist. Within hours of the incident, seven Runners went in search of the robbers, gathering information from pubs and a variety of informers. Two days later, the Runners arrested five men, four of whom were convicted. Three days later, the fifth man who had killed Griffiths, was hanged.

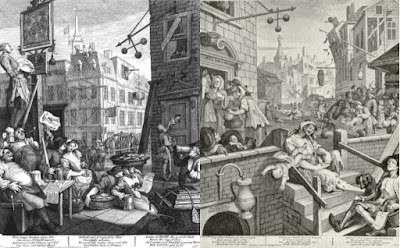

Covent Garden, home to Bow Street, was notorious for its bawdy houses, unlicensed alehouses, and gambling houses – precisely the kind of businesses that drew men into crime. Although at first Sir John did not think regulating morality was part of his job as magistrate, he eventually turned his and his Runners’ attention into policing immoral behaviours involving hard alcohol, gambling, and prostitution. Sir John drew censure when his moral policing widened to include popular dancing.

|

| Beer Street and Gin Alley by William Hogarth (1751) via Wikimedia Commons |

In 1829, Sir Robert Peel created the Metropolitan Police, and Bow Street disbanded in 1839. The first professional detective department was formed in 1842.

Sources:

Cox, David, A Certain Share of Low Cunning: A History of the Bow Street Runners, 1792 – 1839 (Willen Publishing, 2010)

Beattie, JM, The First English Detectives: The Bow Street Runners and the Policing of London, 1750 – 1840 (Oxford University Press, 2012)

About the author: Julie Tetel Andresen has written more than twenty-five romance novels, one of her most recent being John Carter’s Conundrum, a Georgian-era novella whose hero, John Carter, is a Bow Street Runner. Visit Julie's website here where you can download John Carter’s Conundrum for free.

Note

1. This image is being shared under a Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-ND 3.0).