|

| Close up view of the head of the Coade stone statue of George III, Weymouth seafront © A Knowles |

Eleanor Coade (3 June 1733 – 16 November 1821) was a Georgian businesswoman who successfully ran an artificial stone manufactory in London. There are many examples of Coade stone which still exist today including the King’s Statue, Weymouth. You can read more about Eleanor Coade and eleven other inspirational Georgian women in my book: What Regency Women Did For Us.

Early life

Eleanor Coade was born on 3 June 1733 in Exeter, Devon. She was the daughter of George Coade, a wealthy, non-conformist wool merchant, and his wife, Elizabeth Enchmarch. Eleanor had a younger sister, Elizabeth. In 1759, the family fortunes changed when George was declared bankrupt and they relocated to London.

Eleanor's Coade stone

By 1766, Eleanor, still unmarried, was operating as a linen draper. Three years later, seemingly unaffected by her father’s second bankruptcy, she bought an artificial stone manufactory situated at King’s Arms Stairs, Lambeth. Eleanor’s factory could produce in artificial stone almost anything that could be made in real stone, but at a cheaper price. Her products included decorative wall panels, vases and statues. She later diversified into scagliola – fake marble.

Eleanor was able to turn around the failing factory and make it successful. What set her business apart from other artificial stone manufactories was the quality and design of her products. She refined the formula for artificial stone – what she called lithodipyra – and carefully controlled the firing process, making her stone frost-resistant. She also employed top designers, most importantly, fellow non-conformist, the sculptor John Bacon (1740-1799).

|

| View of Coade stone statues including the River God Thames inside the kiln from European Magazine and London Review Volume 11 (1787) |

The Coade Stone Gallery

Eleanor used every opportunity to promote her business. In the late 1790s, she built a gallery at the south bank end of Westminster Bridge where the public could come and view her products. She even sold guidebooks to visitors so that they could take a self-guided tour. The gallery participated so successfully in the peace illuminations of 1801 and 1802 that it was mentioned in The Times.

Eleanor drew people into her business by advertising in the newspaper when she had spectacular commissions on display, such as the colossal statue of Lieutenant-General Lord Hill, or new pieces for sale which she hoped would generate a lot of interest, such as the Warwick Vase.

|

| Entrance to Coade and Sealy's Gallery of Sculpture from European Magazine and London Review Volume 41 (1802) |

The final years

When John Sealy died in 1813, the firm’s name reverted to Coade. Eleanor took on a distant relative, William Croggon, to manage the manufactory, but she did not make him her partner, nor did she leave him the business on her death.

Eleanor died at her home in Camberwell, Surrey, on 16 November 1821 aged 88 years. Her will included bequests to many charities and clergymen, and to numerous single women who were less fortunate than herself.

Coade stone

Coade stone has proved its durability by the number of pieces that have survived 200 years of facing the elements. Here are some that I have come across in my travels:

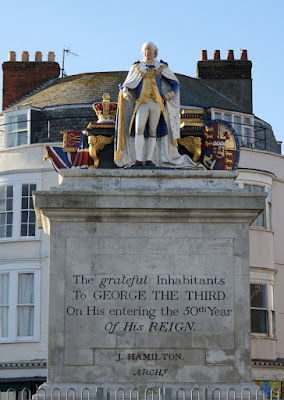

King’s Statue, Weymouth

Coade stone lion in the visitor centre, Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich

The lion was designed by Benjamin West as a trial piece for the pediment in the King William Courtyard commemorating the achievements of Vice Admiral Horatio Nelson.

|

| Coade stone lion, Old Royal Naval College, Greenwich, London |

Belmont House, Lyme Regis

This house was given to Eleanor by her uncle Samuel Coade and is decorated with Coade stone.

|

| Belmont House, Lyme Regis, Dorset |

Coade stone torchere from Carlton House – one at Athelhampton House, Dorset

|

| Coade stone torchere, Athelhampton House, Dorset (2016) |

|

| Gothic conservatory, Carlton House, London, showing the Coade stone torcheres in situ from Ackermann's Repository (1811) |

Borghese Vase in Temple of Flora, Stourhead

|

| Coade stone Borghese Vase in Temple of Flora, Stourhead |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources used include:

Ackermann's Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (1811)

Kelly, Alison, Mrs Coade's Stone (1990)

Roberts, Sir Howard, and Godfrey, Walter H, Survey of London Volume XXIII - South Bank & Vauxhall Part 1 (1951)

The European Magazine and London review, volume 11 (1787)

The European Magazine and London review, volume 41 (1802)

The Times online archive

Ackermann's Repository of Arts, Literature, Commerce, Manufactures, Fashions and Politics (1811)

Kelly, Alison, Mrs Coade's Stone (1990)

Roberts, Sir Howard, and Godfrey, Walter H, Survey of London Volume XXIII - South Bank & Vauxhall Part 1 (1951)

The European Magazine and London review, volume 11 (1787)

The European Magazine and London review, volume 41 (1802)

The Times online archive

All photos © regencyhistory.net

this is the one I remember and saw the most...https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/South_Bank_Lion

ReplyDeleteI came across your wonderful blog today. I'm enjoying reading all your interesting posts.

ReplyDeleteAnn

Thanks for the encouragement. I'm glad you're enjoying my blog. Rachel

DeleteThe story of E. Coade and Coade stone is fascinating. Wonderful that so much is still around.

ReplyDeleteThanks for sharing. I have a booklet about the stone.In one way it is unfortunate that the stone gets mentioned more than the lady.