|

| The auditorium of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

On our way back from holiday in Norfolk, my husband Andrew and I managed to squeeze in a tour of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds – the only surviving Regency theatre in England. I was interested to see inside this restored Grade I listed playhouse to get an idea of what a provincial theatre in late Georgian England, like the one that once existed on Weymouth seafront, would have looked like.

William Wilkins (1778-1839)

|

| Bust of William Wilkins in the saloon of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

The Wilkins family were shareholders in the Norwich circuit of theatres and Bury St Edmunds was the most profitable stop. The previous playhouse was in the centre of town, on the upper floor of the market hall. Although the Market Cross building had been remodelled by Robert Adam in 1774, Wilkins felt it was inadequate.

In 1818, Wilkins purchased a piece of land on Westgate Street for £200. He clearly did not choose this spot for the convenience of his audience. Westgate Street was on the southern edge of the town, which was rapidly expanding on the opposite, northern side. An 1827 book about Bury St Edmunds noted:

The present Theatre is neat and convenient, situate in West-gate-street, it was erected in 1819, but the situation, being so distant from the centre of the town is a source of regret and loss to the proprietors.1

It seems that Wilkins chose this location because of its natural slope. This enabled the pit to be made low enough so as not to obscure the view from the boxes without requiring an excessive amount of excavation.

The theatre was erected in 1819, opening in October. There seems to be some variance as to exactly how much the building cost. According to Miller’s theatre history, By Particular Desire, Wilkins estimated the cost at £4,000, but ended up spending £5,000 and paid the difference himself.

In his History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk (1855), William White wrote:

The Theatre in Westgate street is a commodious structure, which was erected in 1819, in lieu of the old theatre at the Town Hall, at the cost of £3000, raised in £100 shares. 2

The new theatre opened on Monday 11 October 1819 with performances of George Colman the younger’s successful comedy John Bull and a new farce, A Roland for an Oliver. Both were performed by the Norwich Company of touring actors who served Bury St Edmunds. They were reckoned to be one of the best of the provincial touring companies.

The Norwich Company consisted of about 14 people who travelled around such places as Great Yarmouth, Ipswich, Norwich, Stourbridge and Colchester, accompanied by their scenery and costumes. During the period 1814 to 1839, the troupe was managed by James Smith.

The company had their own scenic artist, George Thorne, who was the best paid member of the troupe. He helped decorate Wilkins’s theatres, including Bury St Edmunds.

In his 1821 guide to Bury St Edmunds, Deck wrote:

The Bury theatre is occupied by the Norwich company, under the management of Messrs Smith and Bellamy. The season is during the great fair.3

In his 1855 directory of Suffolk, White wrote that the theatre

... is supplied by the Norwich Company, and is usually open for five or six weeks in October and November.4

Tymms wrote in his Bury St Edmunds handbook of the same year:

It was generally supplied by the Norwich company for several weeks in October and November, but now is opened more or less all the year round.5

The auditorium

|

| The ceiling of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

The stage was large, coming out into the auditorium, so that the front was well lit and allowed interaction between the players and the audience. The stage boxes were level with the stage and enabled the occupants of these boxes, who tended to be the most important people, to both see the play and be seen by the rest of the audience.

|

| Dress circle boxes from the stage Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| The Entrance Saloon, Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| The Entrance Saloon, Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds The doors lead directly to the dress circle boxes (2019) |

|

| Doors to boxes, Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| View across the theatre showing lower tier of boxes Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| View from one of the upper boxes of the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| View from the pit showing the entrance to the right Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

A further 120 people could be squeezed into the gallery, right at the top of the theatre.

|

| View of auditorium showing gallery area just below the ceiling Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| View from the gallery Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

As you would expect, the better the seat, the higher the price of a ticket. As was common at the time, most of the seats had two prices and people could come in for the second half of the entertainment for a reduced price. According to a playbill for 1828, the prices were as follows:

- Boxes 4s - Second Price 2s

- Pit 2s 6d - Second Price 1s 6d

- Gallery 1s - No half-price

A playbill from 1839 showed that the prices had changed – some of them had gone down! This was after Wilkins’s death and one can only assume that the theatre was struggling to fill its seats by this time. The theatre now differentiated between lower and upper boxes, with the lower boxes – what we would call the dress circle – charged at the 1828 rate, but the upper boxes now available at 3s (1s 6d second price). The pit charge was also reduced by 6d to 2s (1s second price) and the gallery now had a second price of 6d.

|

| Another view from the gallery Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

A surviving playbill from 14 October 1824 indicated that seats could be booked of Mr Hunt in the Box Office between the hours of eleven and two.

The theatre must have had a problem with patrons complaining of the cold because on the same playbill, the theatre advertised that fires had been kept going in the theatre constantly, presumably to raise the temperature.

An 1828 playbill stated that the doors would be opened at six and the performance would commence promptly at seven o’clock.

The performances

The Norwich Company usually performed two, or even three, pieces every night. The theatre has a collection of old playbills which give a flavour of what was performed.

|

| 1821 Playbill advertising Lovers' Vows on display at Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

The play advertised for Saturday 3 November 1821 was Lovers’ Vows, followed by Timour the Tartar, a romantic melodrama. Lovers’ Vows is, of course, famous amongst fans of Jane Austen because it is the play that the young people of Mansfield Park were going to perform before they were interrupted by the sudden return of Sir Thomas Bertram. Lovers’ Vows was well-received, having been written by local girl, actress and playwright Elizabeth Inchbald, who was born not far from Bury St Edmunds.

On Monday 5 November 1821, the performances comprised a comedy, The Will, and a farce, The Prize, with Miss Kelly. Frances Maria Kelly was a London actress who was sufficiently well known to be featured in The Ladies’ Monthly Museum in 1819.

|

| Frances Maria Kelly from The Ladies' Monthly Museum (1819) |

A playbill for Friday 7 November 1828 advertised another play by Mrs Inchbald – a farce called Animal Magnetism together with George Barnwell, a tragedy, and The Bandit of the Blind Mine, a melodrama in three acts.

|

| William Charles Macready from The Diaries of William Charles Macready 1833-1851 (1912) |

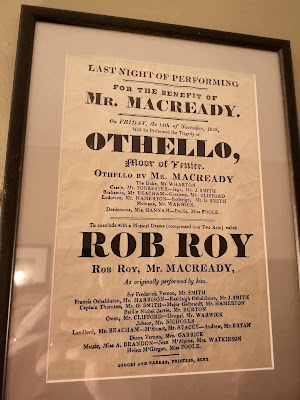

|

| 1828 Playbill advertising Othello and Rob Roy on display at Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

|

| William Charles Macready as Othello from The Diaries of William Charles Macready 1833-1851 (1912) |

The audience

The theatre was patronised by Lord and Lady Bristol of nearby Ickworth House. Another prominent theatre goer was James Oakes, a wealthy merchant and banker, who was a shareholder. The shareholders received silver tokens which gave them free access to the performances at the theatre. There were ongoing arguments as to whether these rights were transferable.

Important patrons and shareholders could bespeak performances, such as the production of Lovers’ Vows in 1821 mentioned above, which was ‘by desire of the subscribers to the theatre.’6

Refreshments included oranges and sweets and it would seem, our theatre guide told us, oysters, as a great number of oyster shells were found during the renovations of the theatre. Clay pipes were also found, indicating that people smoked in the theatre.

|

| Under the stage at Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

After Wilkins died in 1839, the theatre was briefly taken over by James Abington who renamed it the Theatre Royal. In the decades that followed, the theatre’s success dwindled, and in 1920, the Greene King brewery bought the building to use as a barrel store.

Although this meant that, sadly, many of the original, internal fittings were stripped out, the fact that the building was repurposed secured its survival.

In 1965, the restored building reopened as a theatre. In 2005, further restoration work began which has returned the theatre to its Regency splendour.

The Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds, is well worth a visit. The National Trust operates informative tours which I would highly recommend. When they are available, you can book through the theatre website.

|

| Our fantastic tour guide, outside the Theatre Royal, Bury St Edmunds (2019) |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Longman (pub), A concise description of Bury Saint Edmund's and its environs (1827)

2. White, William, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk (1855)

3. Deck, J, A guide to the town, abbey and antiquities of Bury St Edmunds (1821)

4. White, William, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk (1855)

5. Tymms, Samuel, A handbook of Bury St Edmund's with additions by JR Thompson (1855)

6. From an original playbill displayed at the theatre.Sources used include:

Deck, J, A guide to the town, abbey and antiquities of Bury St Edmunds (1821)

Longman (pub), A concise description of Bury Saint Edmund's and its environs (1827)

Tymms, Samuel, A handbook of Bury St Edmund's with additions by JR Thompson (1855)

White, William, History, Gazetteer and Directory of Suffolk (1855)

National Gallery website

National Trust website

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.