|

| Toll house, Blists Hill Victorian Town, Ironbridge (2018) |

A turnpike road was a toll road operated under a trust set up by an Act of Parliament. A Turnpike Act authorised a group of trustees to levy tolls on a stretch of road in order to finance its maintenance and improvement. The toll rates were set by the Act which also empowered the trustees to borrow money secured on future tolls in order to invest in road improvements. Money could be borrowed by bonds and loans secured on the toll income or by mortgaging the tolls.

The term of a turnpike trust was 21 years, but tolls were to cease earlier if the money borrowed had been repaid. Extensions were regularly granted to trusts for ongoing improvement and maintenance.

Turnpike roads got their name from the turnpikes or toll gates which barred the way until the road users had paid the required toll. The turnpikes were placed at strategic points along the road where it was difficult for travellers to evade paying, such as at bridges or where the lie of the land constricted the road.

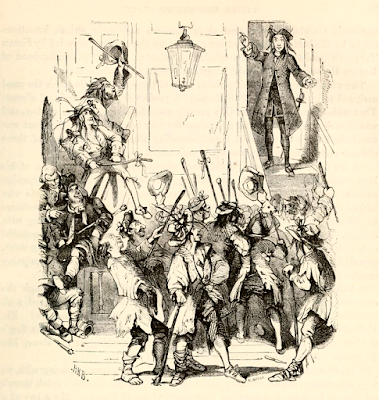

|

| Tyburn Turnpike (1820) from Old and New London by E Walford (1878) |

The state of the roads around large conurbations like London were in a bad state of repair due to overuse. The preamble to a Turnpike Act for Surrey passed in 1718 stated that certain roads

...by reason of the many heavy loads and carriages of meal, timber, stone, hops, and other goods, and great number of stage and hackney coaches, passengers and droves of cattle daily passing through the same, are become so very ruinous and almost impassable, for the space of five months in the year, so that it is dangerous to all persons, horses, and other cattle to pass through the said roads.1

Road maintenance was the responsibility of the parishes through which the roads passed, but they did not have the resources to keep the roads in good repair.

Turnpike Acts provided the means for raising money to build and maintain better roads and allow the fast transport of people, mail and goods from place to place.

When was the turnpike system in operation?

|

| Toll house at the Weald and Downland Living Museum (2014) |

The turnpike system was not a unified road network but rather a large number of individual turnpike roads, operated by different trusts, that provided better road conditions across Britain and Scotland. Generally, the trusts coordinated their improvements to provide continuous stretches of good road, but if they were offering alternative routes to the same place, they sometimes competed with each other, trying to attract traffic and therefore tolls to travel their route.

The first Turnpike Acts were passed in the late 17th century and by the mid-1830s, about 22,000 miles of road in England and Wales – about one fifth of the road network – were managed by turnpike trusts.2 The turnpikes were wound up in the 1870s and the responsibility for road maintenance passed to the Highways Board.

Trusts could either appoint collectors, who would have to sign an oath to confirm they had handed all the tolls over, or they could let the tolls.

An advert in The Times for April 1810 stated the date and place when the trustees of the New Cross Turnpike Roads intended to auction the tolls, giving the sum collected in a previous period as guide price to bidders.3

|

| Toll house, Athelhampton House (2015) |

Toll houses were built next to the turnpikes as someone needed to be collecting the tolls 24 hours a day. These represented a significant investment from the trusts. The standard toll house design adopted in the 1820s was of a small, single-story cottage with a polygonal bay front.

Some toll houses on major roads were built on a rather grander design, with castellated rooves, designed to impress rich travellers and tempt them to use their route over an alternative.

Turnpikes were generally placed outside the town so that local businesses did not have to pay the toll. However, the remoteness of their locations meant that the toll houses were vulnerable to theft and as a precaution, they tended to be fitted with bars and a safe.

Many toll houses were demolished when the turnpike trusts were abolished particularly if their position restricted the width of the road. Others were sold into private ownership.

|

| Spaniards Gate toll house, Hampstead (2019) |

|

| Plaque on side of Spaniards Gate toll house, Hampstead (2019) |

The toll rates for each turnpike were set according to the Turnpike Act that established it and differed according to the type of user.

The Mail did not have to pay tolls. An outrider blew a horn as the coach approached so that the toll keeper could get the gate open ready without the Mail having to slow down.

The Surrey Turnpike Act of 1718 set the rates as follows:

For every horse, mule, or ass, laden or unladen, and for every chaise, cart, dray, or other carriage drawn by one horse, one pennyFor every coach, chariot, or calash drawn by two or more horses, sixpenceFor every waggon not laden with hay or straw, sixpenceFor every waggon laden with hay or straw, threepenceFor every cart, dray, or carriage laden with hay, straw, or other goods, twopenceFor every drove of oxen or neat cattle, twopence per scoreFor every drove of calves, hogs, sheep, or lambs one penny per scoreA ticket for the toll road lasted all day.Soldiers, all persons riding post, and all carts and waggons travelling with vagrants, were permitted to pass free of toll.4

The Sussex Turnpike Act of 1749 set the rates as follows:

For every coach, berlin, landau, chariot, chaise, calash, chair, caravan, or hearse, drawn by six horses or mules, the sum of one shillingIf drawn by four horses, &c., ninepenceIf drawn by two horses, &c., sixpenceIf drawn by one horse, threepenceFor every waggon, wain, cart, or carriage drawn by six horses or oxen, one shilling and sixpenceIf drawn by four horses or oxen, ninepenceIf drawn by two horses or oxen, sixpenceIf by one horse, threepenceFor every waggon or cart, laden only with hay or straw, threepenceFor every horse, mule, or ass, laden or unladen, and not drawing, one pennyFor every drove of oxen, tenpence per scoreFor every drove of calves, sheep, &c., fivepence per score.The Act specifically prohibited the repair of pavements in the streets of any town.Those travelling to county elections were exempt.5

Milestones

Most turnpike trusts put up milestones, marking the distance to significant places.

|

| Milestone in Blandford, Dorset (2016) |

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Parliamentary papers, House of Commons vol 44 (1852)(Turnpike Roads)

3. The Times online archive, April 1810.

4. Parliamentary papers op cit.

5. Ibid.

Sources used include:

Parliamentary papers, House of Commons vol 44 (1852)(Turnpike Roads)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net