|

| Lady Anne Barnard from South Africa a Century Ago (1910) |

Profile

Lady Anne Barnard (née Lindsay) (8 December 1750 – 6 May 1825) was a Scottish travel writer, diarist, poet and amateur artist. Her most famous work is the ballad Auld Robin Grey.1

Early life

Lady Anne Lindsay was born on the family estate of Balcarres in a remote part of Fife in Scotland on 8 December 1750. She was the eldest of the 11 children of James Lindsay, the impoverished 5th Earl of Balcarres, and his wife, Anne Dalrymple, who was 40 years his junior.

Anne’s mother resented being coerced into marrying a man old enough to be her grandfather and she took out some of her dissatisfaction with her lot on her children, especially Anne, who never seemed to get anything right, and often got the violent end of her mother’s temper. Anne’s governess, Henrietta Cummings, made things worse by developing a decided antipathy to Anne.

Anne grew up desperate for the approval that her mother failed to give her and was decidedly wary of a marriage like her mother’s. Anne’s soulmate was her sister Margaret, who was two years younger than her.

An indecisive beauty

Anne was beautiful and intelligent, developing her conversational skills in the Edinburgh salons of her grandmother Lady Dalrymple amongst the best minds in Scotland including the philosopher David Hume. Even with the tattered state of the family estates, Anne had numerous admirers, many of whom would have been happy to lay their worldly goods at her feet. The trouble was that she wasn’t sure she wanted them to. Anne was unconvinced that she liked any of her suitors well enough to marry them and was consequently very indecisive. Unfortunately, this gave the appearance of fickleness.

Eventually she was persuaded to accept one of her suitors, a wealthy merchant with a cork arm named Henry Swinton, but her family put a stop to the engagement when they heard rumours that Swinton was not as rich as they had thought. Poor Anne got the blame and was labelled a coquette – a tag that stuck with her for years.

Auld Robin Grey

Meanwhile, Margaret had fallen in love with an unexceptional young man of good family named James Burges. The relationship came to nothing because her mother thought she could do better. Better came in the form of Alexander Fordyce, a rich banking magnate who coveted Margaret as a prize to be won because of her beauty and birth. They were married in the summer of 1770 when Margaret was just 17. Margaret’s doomed love affair was the inspiration for Anne's most famous poem, Auld Robin Grey.

Anne went to stay with Margaret in London where the two beautiful sisters were much admired. Anne’s chances of making a brilliant match were hindered by the gossip that had followed her from Edinburgh, but she still found a bevy of new admirers including two of Fordyce’s friends – Henry Hope and Richard Atkinson.

Fordyce’s financial ruin

In 1772, Margaret’s world fell apart when Fordyce’s bank collapsed due to his poor speculation. Atkinson was a real friend, protecting her and Anne from the worst of the disgrace. Fordyce went into hiding and the sisters went home to Balcarres. Somehow Fordyce escaped bankruptcy and Margaret was soon back in London with him again.

On the edge of society

Anne did not return to London until after she inherited £300 on the death of her grandmother in 1776. Although back at the centre of London society, somehow she was not quite part of it. Her lack of funds meant that she was living at a very indifferent address and chose to wear colourful, self-made clothes that were decidedly unfashionable. Her Scottish accent was considered vulgar and her unconventional behaviour was labelled ‘odd’ by the ton.

The wicked viscount

Nevertheless, Anne continued to draw admirers and one of these was Thomas Noel, 2nd Viscount Wentworth. She was attracted to the handsome but dissipated viscount and his family supported the match, believing it might be his salvation from ruin. The marriage was widely expected, but Wentworth temporarily backed off because of the demands of his possessive mistress. By the time Wentworth renewed his attentions, after the death of his mistress, Anne realised that she was in love with a cause and not the man. Although her reputation had been compromised, when Wentworth proposed, she refused. Her notoriety as a coquette grew.

Friends in high places

Anne made friends with some of the less respectable members of society, such as Anne, Duchess of Cumberland (née Luttrell), and her disreputable gambling sister Elizabeth. Perhaps it was through them that Anne became acquainted with the young

George IV as he was emerging into adulthood.

|

George, Prince of Wales

from a pencil drawing by John Smart, Jnr (1807)

from The Windham Papers Vol 2 (1913) |

Fitz and the prince

Another of Anne’s friends was the twice-widowed

Maria Fitzherbert, whom Anne affectionately referred to as Fitz when writing to her sister. According to Anne’s memoirs, Fitz was in her box at Covent Garden in early 1784 when George, Prince of Wales, first saw her. Fitz confided to Anne how ardently the prince was pursuing her and persuaded Anne to accompany her abroad to escape his attentions.

The prince bombarded Fitz with love letters and offered to marry her, either publicly when he came of age if she would renounce her Catholic faith, or privately now. Anne advised her to do neither, and for a while it seemed as if her advice had succeeded, but sometime after Anne had returned to London, she discovered that Fitz had agreed to marry the prince.

Anne refused to see Fitz and the prince together and did all she could to persuade them to give up the match, but being the confidante of both, she was still blamed for the outcome. The prince and Fitz were married on 15 December 1785. Anne was not present and her continued refusal to see the couple together led to a cooling of her relationship with Fitz.

|

| Mrs Fitzherbert from The Creevey Papers (1904) |

An heiress?

While Anne was abroad, her friend Atkinson had died. Although Atkinson had proposed marriage to Anne and been turned down, he had remained her friend. He had looked after her and her sister after Margret’s husband Fordyce was ruined a second time. By investing Anne’s £300 inheritance wisely, Atkinson had amassed a small fortune for her. In addition, on his death, he made Anne the major beneficiary of his estate. She should have received as much as £30,000, but it never materialised. Atkinson’s family contested the estate and his firm collapsed without their brilliant senior partner. Maybe Anne could have got something from the estate if she had been willing to fight for it, but she refused to pursue it in court.

Rivals in love and politics

|

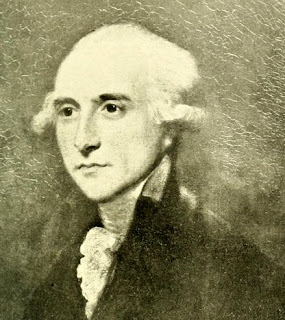

Henry Dundas from Henry Dundas,

Viscount Melville, by JA Lovat-Fraser (1916) |

At this time in her life, Anne had two chief suitors – Henry Dundas and William Windham. Dundas was at the height of his political power and thought Anne would make a fitting wife for a man in his position.

Anne was not interested. She had fallen in love with his political rival Windham. Windham was a brilliant conversationalist and romantically scarred by smallpox. He made Anne the object of his attentions. However, he was renowned for his indecision in parliament and was no better in his private life. He proved to be emotionally manipulative, blowing hot and cold, and keeping Anne hanging on, waiting for a proposal that never came

After refusing Dundas’s marriage proposal in 1791, Anne went to Paris where she observed the French Revolution at close hand. Windham was also in Paris and she gave him access to her hotel room at all hours, blinded to propriety by her obsession. At length, she confronted him and when he started accusing her of using tricks to catch him, she dismissed him. Anne left Paris and returned to London, where Dundas continued to court her as if nothing had happened.

|

William Windham

from The Windham Papers Vol 2 (1913) |

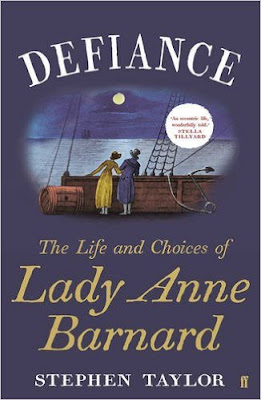

Marriage at last

In 1793, Anne was finally married. Her husband was not the powerful Dundas, but Andrew Barnard, the impoverished son of the Bishop of Limerick who had neither money nor connections to recommend him. Anne had refused his proposals two years earlier, but now, to everyone’s amazement, she accepted him. They were married at

St George’s Hanover Square on 31 October 1793.

2 Society branded Barnard an adventurer, but the marriage was a happy one. As Barnard was a commoner, Anne continued to use her courtesy title as the daughter of an earl and was known as Lady Anne Barnard for the rest of her life.

|

Andrew Barnard from Historic Houses of

South Africa by Dorothea Fairbridge (1922) |

The couple retreated to Ireland where they attempted, unsuccessfully, to live within their limited means. Anne determined to obtain a post for her husband and petitioned Dundas for a position. Eventually Dundas offered Barnard a salaried post – that of secretary to the governor at the Cape of Good Hope in South Africa. This was not quite what Anne had hoped for, but when it became obvious that nothing else was going to be forthcoming, she declared that she would accompany her husband.

Life at the Cape

|

Lord Macartney from

The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs

of Sir Nathaniel Wraxall Vol 4 (1884) |

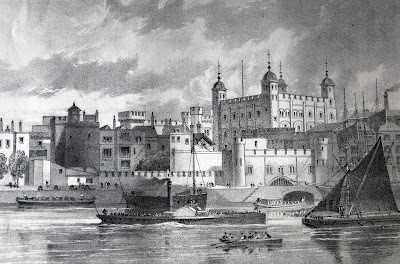

In February 1797, the Barnards sailed for the Cape of Good Hope, where they took up residence in the Castle of Good Hope with the governor, Lord Macartney. Macartney’s wife had not travelled out with him and so Anne acted as his hostess at the Castle. They entertained the army officers and the Dutch colonists as well as visitors who were passing through, such as Richard Wellesley, Lord Mornington, elder brother of the

Duke of Wellington.

Anne maintained a regular correspondence with Lord Mornington after he left for Bengal and thus she could include information about India as well as the Cape in the despatches that she regularly sent to Dundas.

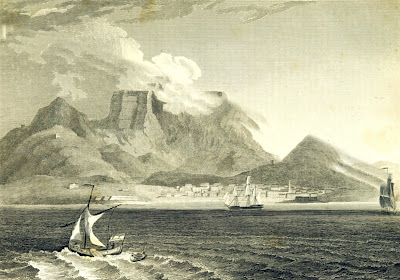

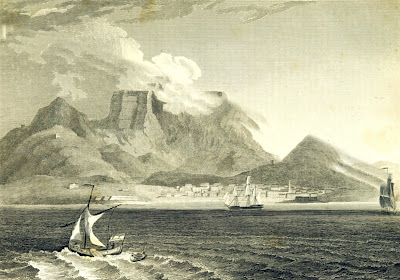

Anne climbed Table Mountain and went on several trips into the interior, recording what she saw both with words and drawings. Her journals reflected on the issues surrounding them, such as the massive slave population in the Cape. The Barnards renovated a run-down cottage named Paradise part the way up Table Mountain and for a while they lived there. Anne called these years the happiest of her life, marred only by her inability to have children.

|

Cape Town and the Table Mountain

from A New Geographical Dictionary by JW Clarke (1814) |

Changes in governorship

Barnard thrived under Macartney’s laid back leadership style, but when the governor returned to England with ill health, the colony was temporarily put under the control of General Dundas, a nephew of Anne’s old suitor. His authoritarian approach and contempt for Barnard made life very difficult. Soon, Barnard was secretary in name only as General Dundas bypassed his approval.

A new governor was appointed, but he was even worse. Sir George Yonge was arrogant and ineffectual and in time, he proved to be corrupt as well. Anne reported to Dundas that Yonge had accepted a huge bribe from an infamous slave trader to land a large number of slaves and, as a result, Yonge was removed from office. In 1801, before another governor could be appointed, Britain made peace with France. The colony was to be handed back to the Dutch.

With the loss of the Cape, Barnard lost his well-salaried post. Anne was worried about getting a new position for her husband as Dundas was no longer in power. In January 1802, Anne travelled back to England to try to gain patronage for her husband in person whilst Barnard stayed at the Cape until the official handover to the Dutch. Neither of them realised it was going to take a whole year.

A disastrous posting

Three years after Barnard’s return, he was still without a post. Finally, in 1806, shortly before he died, Henry James Fox recommended that Barnard should be given his old job back, as secretary to the new governor at the Cape. Windham reluctantly agreed. But having secured the post, Anne panicked that her husband’s health would not stand up to another stint living at the Cape. She pleaded with Windham to give him something else, but he was unmoved. Barnard said he would have to take the post or he could never be expected to be offered anything again. Anne stayed in England to petition on her husband’s behalf.

The new governor, Lord Caledon, was young and inexperienced and relied heavily on Barnard for help. Caledon was a kind man and very concerned about his secretary’s bilious attacks. He was right to be concerned. Barnard’s health got worse and on 27 October 1807, he died.

Surrogate mother

Anne was devastated by her husband’s death and blamed Windham for what had happened. But there was more to come. She received a letter from Lord Caledon telling her about a little mixed race girl, aged about six years old, the illegitimate daughter of her husband and a slave woman. The child had been conceived after she had left for England in 1802. Anne’s reaction was totally unconventional. She excused her husband’s infidelity, blaming herself for leaving him like a widower in South Africa and in 1809, she welcomed the girl, known as Christina Douglas, into her home at 21 Berkeley Square.

Christina was not the only child that Anne took care of. Barnard had fathered two illegitimate sons before his marriage and each of these placed a daughter in Anne’s care – Margaret and Anne Hervey.

Two other family members stayed often with her – Colonel Andrew Barnard, a nephew of her husband who was repeatedly injured in battle, and her nephew James Lindsay, whom she nursed back to health after the disastrous Walcheren Expedition to Holland in 1809.

A sister’s (brief) happiness

In 1812, Anne’s sister Margaret finally entered a few brief years of happiness. She married her old sweetheart James Burges who had recently been widowed. Sadly, it was short-lived; Margaret became ill with a tumour and died two years later.

Final years

In her last years, Anne increasingly lived as a recluse, devoting her time to writing and drawing and preparing a memoir of her life with Christina’s help. Some of her family were afraid of what she was writing, fearing that the contents would bring shame on the family if they got into the wrong hands. Anne was adamant that her work was never to be published and her memoirs remain so today.

In 1822, Sir Walter Scott quoted a verse from Auld Robin Grey in The Pirate, specifically referring to it as Lady Anne Lindsay’s beautiful ballad. After maintaining her anonymity as author through most of her life, she was finally given public credit for her poem. The full poem was published for the Bannatyne Club after Scott’s death.

Death

Anne died on 6 May 1825 at her home in Berkeley Square. She left legacies to all three of the girls who lived with her, and skipping over her brothers, left the rest of her property to her nephews, James and Lindsay.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) The ballad is popularly known by the title Auld Robin Gray spelt with an ‘a’ rather than an ‘e’ but Anne always wrote it with this spelling.

(2) The date is given as 30 October 1793 in Defiance, but 31 October in the Dictionary of National Biography and this is supported by the transcription of the marriage register of St George’s. All three of these sources are listed below.

Sources used include:

Barnard, Lady Anne Lindsay, South Africa a century ago; letters written from the Cape of Good Hope (1797-1801) (1910)

Chapman, John H (ed) The Register book of marriages belonging to the Parish of St George, Hanover Square in the County of Middlesex Vol 2 1788-1809 (1888)

Clarke, JW, A New Geographical Dictionary (1814)

Creevey, Thomas, The Creevey Papers, A selection from the correspondence & diaries of the late Thomas Creevey, MP, edited by Sir Herbert Maxwell (John Murray, 1904, London)

Fairbridge, Dorothea, Historic Houses of South Africa (1922)

Grosart, AB, Barnard (née Lindsay) Lady Anne (1750-1825), rev Trapido, Stanley, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004, accessed 12 Oct 2016)

Lovat-Fraser, JA, Henry Dundas Viscount Melville (Cambridge University Press, 1916)

Taylor, Stephen, Defiance - The Life and Choices of Lady Anne Barnard (Faber & Faber, 2016)

Windham, William,

The Windham Papers Vol 2 (1913)

Wraxall, Sir Nathaniel William,

The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs Sir Nathaniel Wraxall 1772-1784 ed by Henry B Wheatley (1884) Volume IV