|

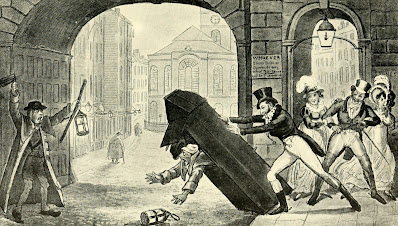

| Tom getting the best of a Charley by George Cruikshank (1820) from The man of pleasure by R Nevill (1913) |

The history of the watchman

|

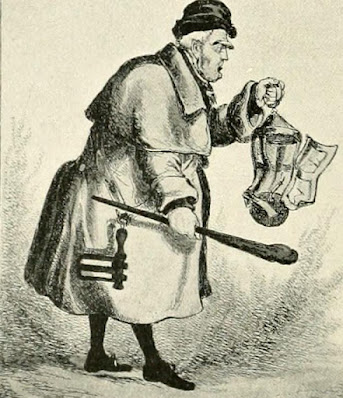

| A watchman from Fifty Years Ago by W Besant (1888) |

Night watchmen had been on the streets of England’s towns and cities since medieval times. Artificial light was a precious commodity, supplied only by the flame, be it in the form of candle, brazier or oil lamp. When it was employed to illuminate a street, such forms of lighting had a limited range. Because huge patches of darkness made it easy for the criminally intentioned to move about unseen, watchmen were a necessary protection.

In London, early night watchmen were householders obliged to carry on the duty on a rota basis.

In a letter to his family, Swiss traveller Cesar de Saussure described the role of the watchman in 1725:

London does not possess any watchmen, either on foot or on horseback as in Paris, to prevent murder and robbery; the only watchman you see is a man in every street carrying a stick and a lantern, who, every time the clock strikes, calls out the hour and the state of the weather.1

In addition, Saussure noted that the watchman used his stick to push on shop doors, alerting the owner if it wasn't fastened correctly.

In 1735, an Act of Parliament allowed the appointment of paid night watchmen in St James', Piccadilly, and St George’s, Hanover Square. Many other Acts followed during the century, providing a system of paid night watchmen that covered most of London. The cost of the watch was passed on to householders through the rates they were obliged to pay the parish.

The professional watchman’s job was to do more than just call out the time and weather and check for loose doors. The Act of Parliament establishing the St Martin-in-the-Fields watch said they were “to prevent as well the Mischiefs which may happen from Fire, as Murders, Burglaries, Robberies, and other Outrages and Disorders.”2

The system of night watchmen in central London ended in 1829, with the creation of the Metropolitan Police. However, it was several years before police forces were established in other town and cities, meaning that in many part of the country, the night watchmen would have continued to serve well into the 1830s. How many of the first police officers would previously have done time in the watch?

The job of the night watchman

Night watchmen were on patrol, usually in pairs, from around 9pm until sunrise and their job was to challenge anyone who seemed suspicious, unauthorised street traders and “any person casting night soil in the street.”3

|

| From Spring-heel'd Jack: the Terror of London by the author of the Confederate's Daughter (1867) |

There’s was not a well-paid or highly respected role, and there seems to have been some concern that some watchmen were too friendly with the criminals they were meant to be watching out for.

Indeed ‘Charlies’or 'Charleys', as watchmen were nicknamed, were caricatured in Georgian prints as often being asleep on the job, allowing criminals to take advantage. This image of the lazy, incompetent watchman goes back at least two hundred years to the time of Shakespeare, who made them comic figures in his play Much Ado About Nothing.

However, at least some Georgian watchmen were not afraid to step in when they thought a crime had been committed. In 1796, John Wilson was stopped by two watchmen in Hanover Square, London, and taken to the constable who, on searching him, discovered pewter pots stolen from a pub.

The dangers of being a watchman

Patrolling the dark streets also meant responding to cries of alarm. On the night of 4 February 1795, at least two watchmen were called by a girl shouting “Watch and murder!” to a house near St Paul’s cathedral. On arrival they were threatened and chased off by an angry householder, John Dunn, who brandished two pistols and threatened to shoot the next watchman who approached his home. He was possibly drunk.

It seems a number of watchmen were attracted to the commotion, perhaps drawn by a moment of excitement in what was often a dull job. So many came that Richard Fitzgerald, who patrolled the area that included the house, had to tell them to go back to their own beats. He also told some of them to stop using their rattle, as the noise seemed to aggravate Dunn.

In his testimony at the Old Bailey some months later, Fitzgerald and other witnesses recalled that Dunn seemed very angry with the watchmen, continually cursing and threatening them as he wandered in the street outside his house. Dunn encountered a trainee watchman, on only his second night, and gave him a real fright by threatening him with the guns.

The episode reached a climax when another watchman, Thomas Price, approached Dunn. For some reason Price was off his beat, perhaps unable to resist the sight of an armed man strutting a London street. Unfortunately, Dunn marched up to Price and, from a distance of just few inches, discharged one of his weapons. Price was killed instantly.

Dunn was tried at the Old Bailey on 16 April 1795, found guilty of murder and sentenced to death. It’s not clear if this was carried out.

The organisation of night watchmen

|

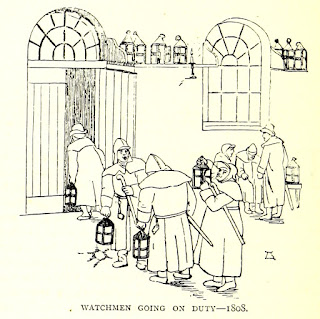

| From The Dawn of the XIXth Century in England by John Ashton (1886) |

The beadle was in charge of the watchmen, responsible for ensuring they were on duty at the correct time and reporting any problems to the churchwardens. Typically, one beadle was on duty at a time.

The watchhouse was the base from which the watchmen operated. It was their store, where equipment was kept, and could also act as a jail when someone needed to be detained. It was also where the watch book was stored, in which they made kept notes of their rounds.

The equipment of a night watchman

Contemporary illustrations of watchmen by Cruikshank and others show the typical items a watchman would have carried or used.

|

| Master Dogberry the Parish Watchman from Social England by HD Traill and JS Saumarez (1901) |

Coat. It’s no surprise that a watchman would usually be wearing a long, thick coat. Even at the height of an English summer it can get chilly in the early hours of the morning.

Hat. Every respectable, and even disreputable, Georgian had at least one hat. The watchman’s was less about fashion and more about practicality, having a wide brim to help against the rain on a damp night.

Hut. The watchman’s hut, similar in appearance to a sentry box, would have been a familiar sight on urban streets. One of Cruikshank’s illustrations, from 1820, shows young men showing off to their ladies by tipping one over, complete with its hapless occupant.

Lantern. Illustrations and written accounts suggest that candles were commonly used as a light source.

Rattle. Watchmen carried a rattle, a wooden device that made a loud clattering sound when spun on its handle. In contemporary accounts, the action of using a rattle was variously described by watchmen as: ‘rung my rattle’, ‘swung my rattle’, ‘turned my rattle’, ‘played the rattle’ or ‘sprung the rattle’.

Staff. A long wooden stick that could be used for self-defence or for prodding a sleeping drunk.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who wrote this post.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Cesar de Saussure, A foreign view of England in the reigns of George I and George II, (1902) p68.

2. Elaine A Reynolds, Before the Bobbies - The Night Watch and Police Reform in Metropolitan London, 1720-1830 (Macmillan Press Ltd, 1998) p24.

3. Dan Cruickshank and Neil Burton, Life in the Georgian City (Viking, 1990) p18.

2. Elaine A Reynolds, Before the Bobbies - The Night Watch and Police Reform in Metropolitan London, 1720-1830 (Macmillan Press Ltd, 1998) p24.

3. Dan Cruickshank and Neil Burton, Life in the Georgian City (Viking, 1990) p18.

Sources used include:

Cruickshank, Dan and Burton, Neil, Life in the Georgian City (Viking, 1990)

Emsley, Clive, Crime and Society in England 1750-1900 (Pearson Education Ltd, 4th edition 2010)

Reynolds, Elaine A, Before the Bobbies - The Night Watch and Police Reform in Metropolitan London, 1720-1830 (Macmillan Press Ltd, 1998)

Saussure, Cesar de, A foreign view of England in the reigns of George I and George II (1902)

the rattle hasn't changed has it? looks just like a football rattle. You didn't mention 'boxing charley' the 'sport' of young blades of turning a watchman in his box round and trapping him against a wall on the side the door is, a variant on tipping him over that Cruikshank showed here so well. I believe I am correct in saying that the watch did NOT have powers of arrest and had to hand miscreants into the hands of a constable who did.

ReplyDeleteWasn't aware of 'boxing charley'. Are there any reliable sources for this? As for making arrests, they certainly had the power to take someone to the watchhouse or constable. What's the history of the conceprt of 'arresting' someone, I wonder?

ReplyDeleteI've come across it a few times in books on the era, but I'm bothered if I can recall which offhand. One was a history of policing which I had from the library. I heard the term first in Georgette Heyer and went looking, but it was a long long time ago.

ReplyDeleteI believe that the word 'arrest' defines seizing to hand to the authorities. The word in that definition is attested to 1598 in the OED.

I'll keep my eyes open for 'boxing charley' in primary sources.

DeleteThere are many references in:Down and Out in Eighteenth Century London-Tim Hitchcock 2004

ReplyDeleteThat sounds like an interesting book. May need to put it on my Christmas list. Thanks for sharing, Ron.

DeleteFirst use of 'boxing a charlie' seems to be The Flash Dictionary (1821).

ReplyDeleteThe illustration comes from: Pierce Egan 'Life in London' (1821) (popularly known as 'Tom and Jerry' - who are pictured with their girlfriends): ‘This song has reminded me of a bit of fun which I had intended, Jerry, to have shown you before you left London. It is ‘Getting the best of a Charley;’ and I will put you up to it before we go to sleep tonight.’

interesting! it's not in the 1811 dictionary of the vulgar tongue; interestingly, Charley itself is not in there.

ReplyDeletethere are quite a few of the 1,423 watercolours of the 1820s in the Bristol Braikenridge collection of stone or timber Charlie boxes.

ReplyDelete