|

| Lady Beauchamp, later 2nd Marchioness of Hertford by John Hoppner (1784) from John Hoppner RA by WD McKay and W Roberts (1909) |

Isabella Ingram Seymour Conway, Marchioness of Hertford (10 June 1759 – 12 April 1834), was the intimate friend and possibly mistress of George, Prince of Wales, later George IV, from 1807 to 1819/20.

Family

Isabella Anne Ingram was born on 10 June 1759, the daughter of Charles Ingram, 9th Viscount Irvine (1727-1778), and his wife, Frances Shepheard (1733-1807). She had a younger sister Frances, but no brothers, and was consequently the joint heir of her father’s estate.

Wraxall described Isabella as one ‘of the riches heiresses of high birth to be found in England.’1

Marriage

On 20 May 1776, the 16-year-old Isabella became the second wife of Francis Seymour Conway, Viscount Beauchamp, later 2nd Marquess of Hertford (1743-1822), who was twice her age. They had one son, Francis, who was born on 11 March 1777. When Isabella’s mother died on 20 November 1807, Isabella and her husband took the additional surname Ingram in acknowledgement of the fortune they inherited.

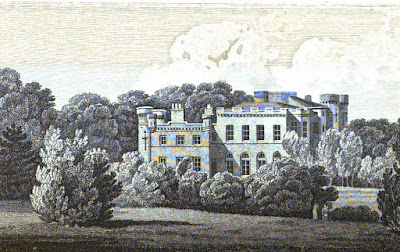

In 1797, Isabella’s husband became 2nd Marquess of Hertford on the death of his father, with an income in excess of £70,000 a year. His estates included Ragley Hall in Alcester, Warwickshire, and Sudbourne Hall in Suffolk as well as large estates in Ireland.

He bought the lease of Manchester House in 1797 and this became the Hertfords’ main London residence. Later renamed Hertford House, it now houses The Wallace Collection. Isabella inherited Temple Newsam in Leeds from her mother in 1807.

The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1816) judged the marriage a success. It wrote:

It is pleasing to record, after a matrimonial union of forty years, that the domestic felicity of Lord and Lady Hertford continues unimpaired; and the same cordiality and esteem still exists, which have ever marked the noble family as worthy of emulation.2

|

| Hertford House, previously Manchester House, in Manchester Square, London. Once the main London residence of Lord Hertford, it is now home to The Wallace Collection |

The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1816) wrote:

The Marchioness of Hertford inherited from her father considerable personal property, and by nature was endowed with much personal beauty, which, with uncommon mental acquirements, have ever rendered her the ornament and admiration of the higher circles of society, where her birth and alliance entitle her to associate.

It continued:

The Marchioness is in her person, although tending to the embonpoint, at once graceful and elegant, her manners are uncommonly fascinating, and notwithstanding she has passed, what is usually called, the meridian of life, being now in the fifty-eighth year of her age, it must be confessed, that her ladyship still possesses the charms of attraction, very superior to many of greater juvenility.3

Not everyone thought her so engaging. Lord Holland wrote:

Her character was as timid as her manners were stately, formal and insipid.4

Lady Hertford first started to attract the young George IV in 1806. The Prince was fighting a battle for the guardianship of Minney Seymour, the ward of his secret wife, Maria Fitzherbert. In an appeal to the House of Lords, the Prince used his influence to have Lord and Lady Hertford appointed Minney’s guardians, having been assured that they would not remove her from Maria Fitzherbert’s care.

What Mrs Fitzherbert perhaps did not foresee was that once the appeal was won, the Prince would lose interest in her. He fell in love with the beautiful Lady Hertford instead.

That same year, the Prince visited Lady Hertford at Temple Newsam and gave her some Chinese wallpaper and the Moses tapestries. He wrote to her repeatedly and made himself ill trying to win her affections.

Lord Hertford tried to avert the Prince’s attentions by taking his wife to Ireland, but this just increased the Prince’s passion. By the summer of 1807, the Prince was regularly visiting Lady Hertford, at both Ragley Hall and Manchester House.

Wraxall wrote that Lady Hertford

… besides the gifts of fortune, had received from nature such a degree of beauty as rarely bestowed upon woman. Lady Beauchamp, in 1785, though even then no longer in her first youth, possessed extraordinary charms. At the present time, in 1818, when she numbers over her head nearly sixty winters, she is still capable of inspiring passion. That she does indeed inspire passion in some sense of the word, must be assumed from the empire which she maintains at this hour over the regent; - an empire depending, however, from the first moment of its origin, more on intellectual and moral endowments, than on corporeal quantities, and reposing principally on admiration or esteem. We may reasonably doubt whether Diana de Poitiers, Ninon de l’Enclos, or Marion de l’Orme, three women who preserved their powers of captivating mankind even in the evening of life, could exhibit at her age finer remains of female grace than the Marchioness of Hertford retains at the present day.5

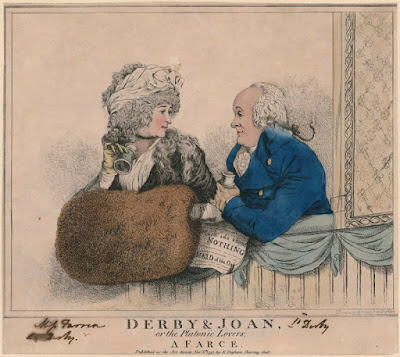

There is some debate as to whether Lady Hertford was the Prince’s mistress or just his intimate friend. TJ Hochstrasser believed that the relationship was platonic; Saul David, on the other hand, found it hard to believe that a man with such a voracious sexual appetite as the Prince would not have made Lady Hertford his mistress.

|

| George IV as Prince of Wales by John Hoppner © The Wallace Collection |

Lady Hertford’s influence

Lord and Lady Hertford were loyal Tories. When William Pitt the Younger began his second term as Prime Minister in 1804, Lord Hertford was appointed Master of the Horse. When he lost his position on Pitt’s death in 1806, he was compensated with the Order of the Garter.

During the time whilst Lady Hertford was the Prince’s favourite, she heavily influenced his politics and drew him away from his Whig friends.

Lady Hertford was very ambitious to advance her family’s position. She used her influence with the Prince of Wales to obtain the position of Lord Chamberlain of the Household for her husband in 1812 and her son Francis, Lord Yarmouth, who had become a member of the Prince’s set, was made Vice Chamberlain. She failed, however, to obtain the dukedom for her husband that she so desired.

The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1816) wrote:

The Royal Family, in particular, have always shown great favour and partiality to the Marchioness of Hertford, and the confidence and honours bestowed on the Marquis and the Earl of Yarmouth, have been, we presume, in a great measure the consequences of the Marchioness’s influence.6

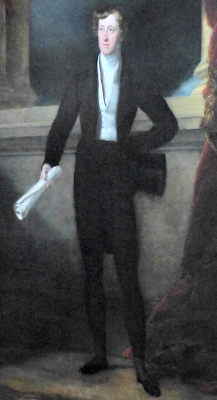

|

| Francis Ingram Seymour Conway, 3rd Marquess of Hertford by Thomas Lawrence (c1822-3) at The Wallace Collection (2015) on loan from National Gallery of Art, Washington |

Lady Hertford was ousted as the Prince’s favourite by another grandmother, Elizabeth, Marchioness of Conyngham, around 1819.

Lord Hertford died on 17 June 1822 at Manchester House and his wife died 12 years later, on 12 April 1834.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. Wraxall, Sir Nathaniel William, Posthumous Memoirs of his own time (1836) Volume I.

2. The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1816).

3. Ibid.

4. Lord Holland quoted in David, Saul, The Prince of Pleasure (Little, Brown & co., 1998).

5. Wraxall op cit.

6. The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1816).

Sources used include:

David, Saul, The Prince of Pleasure (Little, Brown & co., 1998)

Hochstrasser, TJ, Conway, Francis Ingram-Seymour, 2nd Marquess of Hertford (1743-1822), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004, updated 2008)

The Ladies’ Monthly Museum (1816)

Wraxall, Sir Nathaniel William, Posthumous Memoirs of his own time (1836) Volume I

All photographs © RegencyHistory