|

| Skating Lovers (1800) Drawn by Adam Buck; published William Holland; engraved by Piercy Roberts & JC Stadler © The Trustees of the British Museum Used under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) |

|

| Winter, figures skating (1790-1811) Drawn by Isaac Cruikshank © The Trustees of the British Museum Used under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) |

In time of frost, the Canal in St. James's park, and the Serpentine River in Hyde-park, are covered with skaiters; here a stranger will find much amusement.1

In severe winters, when the Serpentine River is frozen over, the ice is almost, covered with people. In one winter there were counted more than 6000 people at one time on the ice. A number of booths were pitched for the refreshment of the populace; and here and there was a group of six, eight, or more, fashionable young men, skaiting, and describing difficult figures, in the manner of a country dance, with peculiar neatness and facility of execution. In general, however, the English do not excel in this exhilarating and wholesome exercise.2

|

| Fashionable figures ice skating (c1795-1810) French school (?) © The Trustees of the British Museum Used under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) |

The Serpentine RiverWas yesterday a scene of attraction. The banks on the north-side were lined with elegant equipages, and those on the south with numerous groups of pedestrians. The day was cheered by the rays of the sun having dispersed the fog. The air, although keen, was invigorating. The ice was good, and the skaiters were in numbers incalculable.A subscription of several guineas having been made for the sweepers (they forming a strong phalanx) the circles were kept in good order. As is customary the best performers were confined within a very narrow space next to the edge nearest the carriages.Here exhibited their skill in circles and figures; on Saturday, the Honourable Mr Byng, of the Torrington Family, Mr Cavendish Bradshaw, Colonel Arthur Upton, Mr Stanhope, and Mr Grant. Mr Upton particularly excelled in what school-boys call a Turk’s-cap ie cutting the figure of three, three times, and thus forming an entire circle. We have seen Mr Cavendish Bradshaw skait more adventurously, but never with a greater degree of elegance and precision. – Lord Cochrane performed very well for a British tar; his efforts never exceeded a straight forward movement. Mr Chisholm, that elegant young man of fashion, and Mr Scott, were among the learners.3

The beautiful Mrs Russell Manners was among the humble pedestrians on the ice on Saturday. She was habited in buff kerseymere, with a broad margin of blue velvet; the costume was strictly a la Spaniola.4

|

| Winter Amusements - A Scene in France (1803) Published by Laurie & Whittle © The Trustees of the British Museum Used under Creative Commons Licence (CC BY-NC-SA 4.0) |

Among the fashionables who took the diversion of skaiting on the Serpentine River on Wednesday was the Duke of Argyle. An elegant female, in a green spotted dress, with a scarlet Spanish mantle, was attended by two Gentlemen. They were allowed by the amateurs to be perfect masters of the art; but the Gentlemen were decidedly excelled by the Lady, who cut out the letters O.P. with a precision and neatness truly astonishing.5

Serpentine RiverThe skaiters continue to be very numerous. A young Lady made a very conspicuous appearnce yesterday. She was attended by a servant, and appeared to take particular delight in sliding. The peculiarity attached to her was her dress, which resembled the covering of a swan, being a pelisse made entirely of swan’s down, and white feet.6

I went in the carriage with Sir Gore Ouseley and some other friends to the park. The weather was so cold that the river was frozen over and a large crowd of men and women was gathered there. Some of them had razor-sharp iron blades fixed to the soles of their boots and they moved like arrows across the ice. They say that ice-skating is a healthy winter exercise. If the ice should break and someone fall in, small boats are at hand to come to the rescue.I conceived a fancy to slide on the ice in the English manner and we got out of the carriage. But there was such a crowd of milling people that I soon lost courage.7

|

| Boat house of the Royal Humane Society from The story of the London Parks by J Larwood (1874) |

From the number of accidents which happen annually on this river when frozen over, his majesty gave the Humane Society a spot of ground on its banks, on which they have erected a most convenient receiving-house for the recovery of persons apparently drowned; it cost upwards of 500l and is worthy the inspection of the curious. The society, during the time of frost, keep men on the river to guard the unwary from danger, and to relieve those who may require their aid.8

|

| Cold Broth and Calamity by Thomas Rowlandson after Henry Wigstead (1792) The Met Museum DP885280 |

All the ponds and rivers in the neighbourhood of London were completely frozen, and skating was pursued with great avidity on the Canal in St James’s, and the Serpentine in Hyde Park. On Monday, the 10th of January, the Canal and the Basin in the Green Park were conspicuous for the number of steel-shod heroes who covered their glossy surfaces, and who, according to their respective qualities, administered to the pleasure of the throng which crowded their banks; some by the agility and grace with which they performed their evolutions, and others by the tumbles and other accidents which marked their clumsy career. There was, as usual, a motley collection of all orders of his Majesty’s subjects, engaged in the busy scene, who seemed all alike eager candidates for the applause of the multitude, and whether sweep, dustman, drummer, or beau, each seemed conscious of possessing some claim, not only to his own good opinion, but to that of the fair belles who viewed his movements. There were several accidents in the course of the day, but none we believe of a serious nature.

While these Parks were thus numerously attended, Hyde park had to boast of a more distinguished order of visitors, who, in the course of the afternoon, flocked in prodigious crowds to the banks of the Serpentine, which was covered with most excellent ice. Notwithstanding the keenness of the breeze, several females of dash, clad in robes of the richest fur, bid defiance to tis chilling embrace, and, on the fragile bosom of the river ventured their fair frames. The skaters were in great numbers, and were of first-rate note. Some of the most difficult movements of the art were executed with an agility and grace which excited universal admiration.

A lady and two officers performed a reel with a precision scarcely conceivable, and attracted a very numerous circle of spectators, whose boisterous applause so completely terrified the fair cause of their ecstasy, as to induce her to forego the pleasure she herself received from the amusement, and to put an end to that which she afforded to such as were disposed to admire her in silence.

Two unfortunate accidents occurred; one skating lady dislocated the patella or kneepan, and five gentlemen and a lady were immersed in the icy fluid, but received no farther injury than a severe ducking.9

On the 22d of January, and for some days afterwards, the ice on the Serpentine River exhibited a singular appearance, from the mountains of snow which the sweepers had collected together in different situations. The spaces allotted for the skaters were in the forms of circles, squares, and oblongs. Next to the carriage ride (on the north side) were many astonishing evolutions displayed. Skipping on skates, and the Turk-cap backwards, were among the most conspicuous.10

|

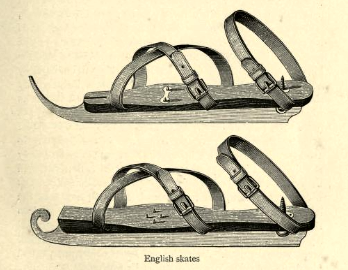

| English skates from Skating by JM Heathcote et al (1892) |

Frostiana stated:

The English, though often remarkable for feats of agility upon skates, are very deficient in gracefulness; which is partly owning to the construction of the skates. They are too much curved in the surface which embraces the ice, consequently they involuntarily bring the users of them round on the outside upon a quick and small circle; whereas the skater, by using skates of a different construction, less curved, has the command of his stroke, and can enlarge or diminish the circle according to his own wish or desire.11It compared the English to the Dutch:

To the native of Holland, skating is quite as familiar as walking, and he puts on his skates with the same indifference as we do our shoes; - the instruments, indeed, are indispensable to the Dutch in the winter season; and are used by men, women and children, constantly … Skating is pursued in England as an amusement only, and for a single week, perhaps, in the course of the year; but in Holland, it is absolutely necessary, and supplies a cheap and commodious method of transport to all classes of people.

The Dutch skates are not so finely shaped as those we use; and the skaters are more remarkable for the ease, than elegance of their execution.12

|

| Skaters on the reservoir at La Villette (1813) Fashion in Paris (1898) from British Library |

We have heard that some skaters in the fens of Cambridgeshire and Huntingdonshire, have skated two miles in two minutes, the strokes on an average being each ten yards. This velocity exceeds that of most race horses, and the fatigue occasioned by it is much less.

A very remarkable skating-feat is said to have taken place during the late frost. A Mr Maxwell, celebrated for his skill and dexterity in this useful art, skated from Long Acre to St James’s Park in four minutes and fifty seconds. This was for a wager, and the given time was five minutes.13

I have not come across anything to say that Jane Austen skated, but her brother Frank loved to skate. Jane Austen wrote to her sister Cassandra from Southampton in January 1807:

We did not take our walk on Friday, it was too dirty, nor have we yet done it; we may perhaps do something like it to-day, as after seeing Frank skate, which he hopes to do in the meadows by the beech, we are to treat ourselves with a passage over the ferry. It is one of the pleasantest frosts I ever knew, so very quiet. I hope it will last some time longer for Frank's sake, who is quite anxious to get some skating; he tried yesterday, but it would not do.14

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

8. Davis, George, Frostiana; or a history of the River Thames in a frozen state (1814)

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid.

11. Ibid.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Jane Austen to Cassandra, January 7, 1807 in Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892)