|

| A Table D'Hote or French Ordinary in Paris by Thomas Rowlandson (1810) The Met Museum DP883708 |

When did a Regency lady eat her dinner?

When you’re writing a novel set in the Regency, it’s the simple things like mealtimes that can trip you up. It might not matter to everyone whether these facts are right or not, but I like to try and get the details as accurate as possible.

I’ve already blogged about breakfast here and lunch here. This post looks at dinnertime.

Did a Regency lady mean the same thing by the term ‘dinner’ as I do? And when did she eat her dinner? Was it at a fixed time every day or did it vary?

|

| Dining Room, Saltram House (2014) |

The definition in the 1810 version of Samuel Johnson’s Dictionary is:

Dinner – the chief meal of the day.1

The definition in Johnson’s earlier 1785 version is:

Dinner – the chief meal; the meal eaten about the middle of the day.2

And the definition in Thomas Dyche’s 1771 dictionary is:

Dinner – the meal or quantity of food a person eats about noon.3

The latter definitions are throwbacks to earlier years when dinner was eaten around noon or even earlier. However, by the Regency period, dinner was no longer eaten in the middle of the day, but during the afternoon or evening. It seems that dinner continued to mean the substantial nature of the meal even when the time of eating changed.

This fits with my experience of the word dinner. I would only use the word dinner to refer to my main meal of the day, though I usually eat it in the evening and sometimes call it supper.

When was dinnertime?

There is no definitive answer to this question! Dinnertime varied as much in the Regency as it does today. That said, we can build up a picture of when people tended to eat their dinner using contemporary sources, such as letters, journals and novels written in the period. Some of the best sources I have found are the journals of foreign visitors, who tended to note customs that were different from their own.

Dinnertime was affected by many factors: class; town or country; fashionable or less fashionable; dining as a family or giving a dinner with guests; on the road or at home.

As a visitor to England in 1810, Don Manuel Alvare Espriella wrote:

The dinner hour is usually five: the labouring part of the community dine at one, the highest ranks at six, seven, or even eight.4

|

| The Dashwoods at dinner with the Middletons Sense and Sensibility by Jane Austen (1811) Illustration by Hugh Thomson (1896) |

In the country, people tended to eat earlier than in town. Because of its association with London, eating later was seen as more fashionable.

In December 1798, Jane Austen, at home in Steventon, wrote to her sister Cassandra who was staying in the more fashionable Godmersham with their brother Edward:

We dine now at half after three, and have done dinner I suppose before you begin—We drink tea at half after six.—I am afraid you will despise us.5

Jane’s dinnertime had shifted somewhat by 1808. She wrote to her sister in December:

Kitty Foote came on Wednesday; and her evening visit began early enough for the last part, the apple-pie, of our dinner, for we never dine now till five.6

In Pride and Prejudice, when Elizabeth is staying at Netherfield:

At five o’clock the two ladies retired to dress, and at half-past six Elizabeth was summoned to dinner.7

The time of dining shifted later still as the Regency progressed and the start time for performances at the theatre were moved later to accommodate this. Feltham’s Picture of London for 1818 says:

The modern dinner hours of 7, 8, and 9 o'clock, have doubtless interfered with the frequent attendance of a large portion of the population, at entertainments which take place between the hours of 6 and 11; yet two theatres, through a season of 200 playing nights, each capable of containing 3000 persons, are moderately filled, and often crowded. To accommodate the public, the theatres have altered their times of beginning to seven o'clock.8

In her inimitable manner, Jane Austen poked fun at the fashionable custom of eating later and later in her unfinished novel, known as The Watsons:

He [Tom Musgrave] loved to take people by surprise with sudden visits at extraordinary seasons, and, in the present instance, had had the additional motive of being able to tell the Miss Watsons, whom he depended on finding sitting quietly employed after tea, that he was going home to an eight-o'clock dinner.

Tom Musgrave stayed past his stated dinnertime:

The carriage was ordered to the door, and no entreaties for his staying longer could now avail; for he well knew that if he stayed he must sit down to supper in less than ten minutes, which to a man whose heart had been long fixed on calling his next meal a dinner, was quite insupportable.9

|

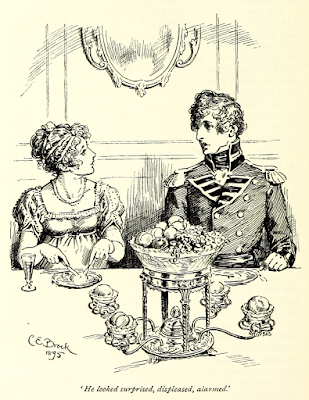

| Elizabeth Bennet and Mr Wickham at dinner Pride and Prejudice by Jane Austen (1813) Illustration by C E Brock (1895) |

A dinner entertainment

According to Samuel Johnson’s dictionary (1810):

Dine – to eat, or give a dinner.10

A dinner entertainment would be more elaborate and last much longer than a family dinner.

In the journal of his visit to London in 1810, the Persian ambassador wrote that a dinner lasted for four hours, from 6pm to 10pm.11

In Pride and Prejudice, Mrs Bennet mourns the fact that Mr Bingley is not able to join them for dinner because he has gone out of town:

After lamenting it, however, at some length, she had the consolation that Mr Bingley would be soon down again and soon dining at Longbourn, and the conclusion of all was the comfortable declaration, that though he had been invited only to a family dinner, she would take care to have two full courses.12

|

| Dinner in Celebration of the Emancipation of Holland from France, City of London Tavern, Bishopsgate December 14, 1813 after Thomas Rowlandson (1814) The Met Museum DP885293 |

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes1. Johnson, Samuel, Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language in Miniature, Rev Joseph Hamilton (1810).

2. Johnson, Samuel, A Dictionary of the English Language (6th edition 1785).

3. Dyche, Thomas and Pardon, William, A New General English Dictionary (14th edition 1771).

4. Espriella, Don Manuel Alvare, Letters from England, translated from the Spanish by Robert Southey 3rd edition (1814) Volume 1.

5. Austen, Jane, Jane Austen's Letters, Collected and Edited by Le Faye, Deirdre (Oxford University Press, 1995).

6. Ibid.

7. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813).

8. Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818).

9. Austen, Jane, The Watsons (a fragment published in Austen-Leigh, James Edward, Memoir of Jane Austen (1871)).

10. Johnson, Samuel, Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language in Miniature, Rev Joseph Hamilton (1810).

11. Hassan Khan, Mirza Abul, A Persian at the Court of King George 1809-10, edited by Margaret Morris Cloake (1988).

12. Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813).

Austen, Jane, Emma (1815)

Austen, Jane, Jane Austen's Letters, Collected and Edited by Le Faye, Deirdre (Oxford University Press, 1995)

Austen, Jane, Mansfield Park (1814)

Austen, Jane, Northanger Abbey (1817)

Austen, Jane, Pride and Prejudice (1813)

Austen, Jane, Sense and Sensibility (1811)

Austen, Jane, The Letters of Jane Austen selected from the compilation of her great nephew, Edward, Lord Bradbourne ed Sarah Woolsey (1892)

Austen, Jane, The Watsons (a fragment published in Austen-Leigh, James Edward, Memoir of Jane Austen (1871))

Cruickshank, Dan and Burton, Neil, Life in the Georgian City (1990)

Dyche, Thomas, A New General English Dictionary (1740)

Dyche, Thomas and Pardon, William, A New General English Dictionary (14th edition 1771)

Espriella, Don Manuel Alvare, Letters from England, translated from the Spanish by Robert Southey 3rd edition (1814) Volume 1

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Hassan Khan, Mirza Abul, A Persian at the Court of King George 1809-10, edited by Margaret Morris Cloake (1988)

Johnson, Samuel, A Dictionary of the English Language (6th edition 1785)

Johnson, Samuel, Johnson's Dictionary of the English Language in Miniature, Rev Joseph Hamilton (1810)

Pettigrew, Jane and Richardson, Bruce, A Social History of Tea (2014 edition)

Simond, Louis, Journal of a Tour and Residence in Great Britain, during the years 1810 and 1811 (1815)

All photographs © Regencyhistory.net

Interesting information. I loved the detail and research you put into this article.

ReplyDelete