|

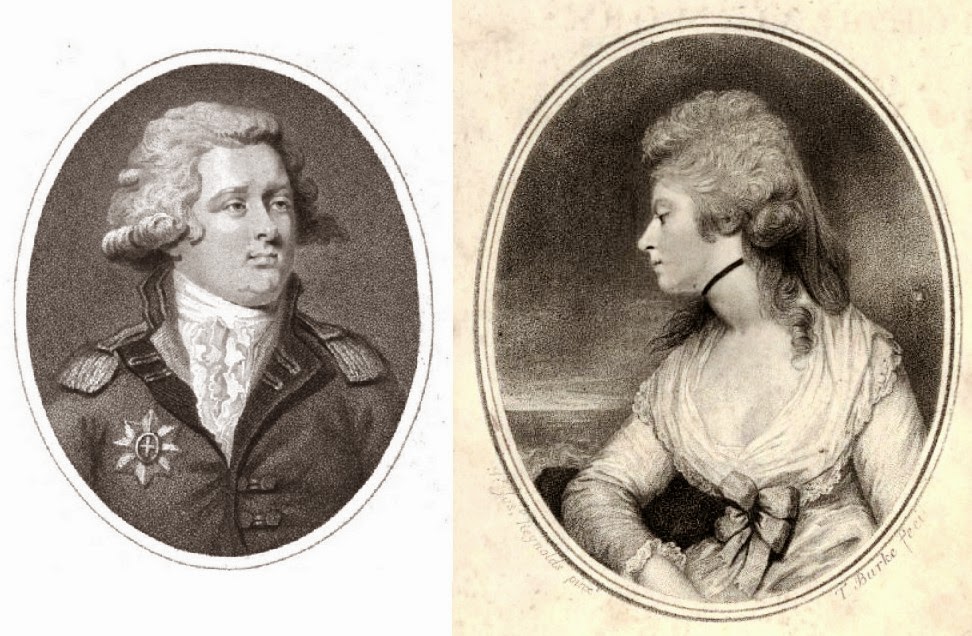

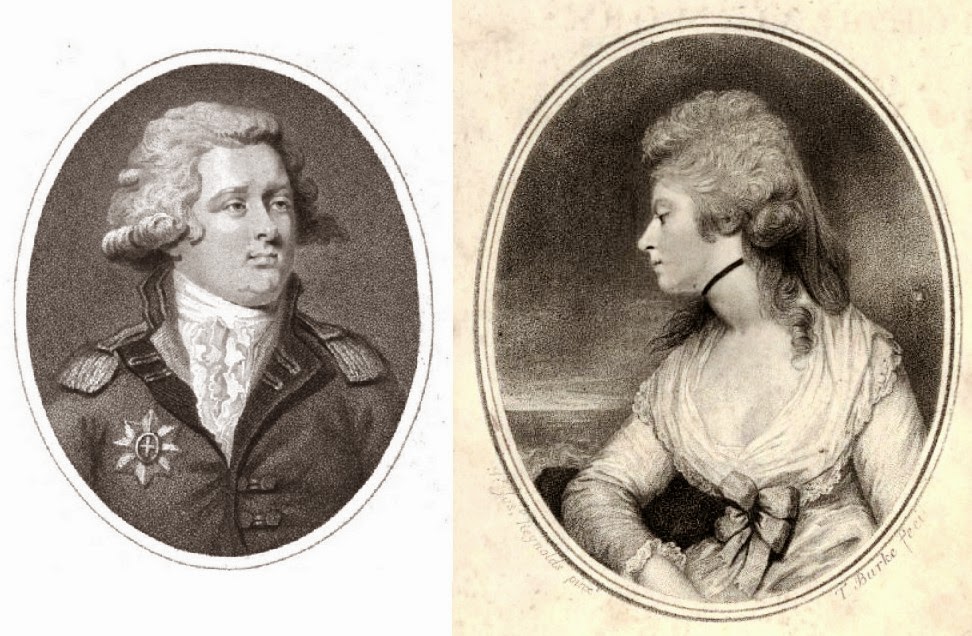

Left: Florizel - George, Prince of Wales from The Lady's Magazine (1792)

Right: Perdita - Mary Robinson from The Poetical Works of

the late Mrs Mary Robinson (1806) |

Who was Perdita?

On Saturday 20 November 1779,

Mary Robinson first played the part of Perdita at the

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane. Perdita was the female lead in

Perdita and Florizel, David Garrick’s adaptation of the last two acts of Shakespeare’s

A Winter’s Tale.

Rather than the flowing pretty dress usually worn by Perdita, Mary sported a closely fitted jacket with the red ribbons of a common milkmaid. Although this costume was criticised in some of the papers, it undoubtedly contributed to Mary’s success.

Mary Robinson

Mary had been about to launch her theatrical career in 1773 but had been persuaded to get married instead. Her husband was Thomas Robinson, an indigent solicitor’s clerk, who had lied about his future prospects. The couple lived beyond their means and, desperate for money, Robinson agreed to Mary becoming an actress.

Richard Brinsley Sheridan engaged Mary to perform at his theatre in Drury Lane. David Garrick, who had coached her for her 1773 debut that had never taken place, loyally came out of retirement to prepare her for the part of Juliet. Mary gave her first performance on 10 December 1776 to widespread acclaim.

|

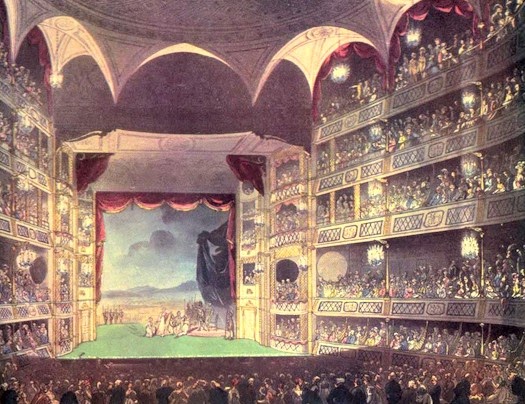

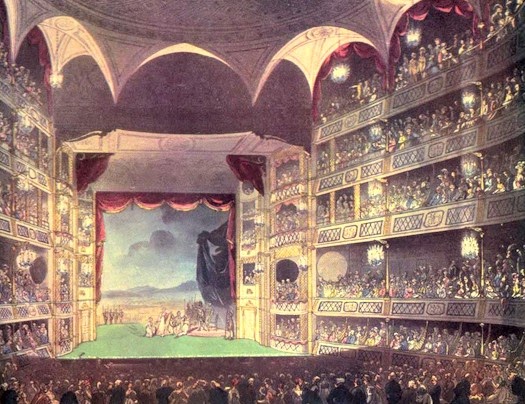

Theatre Royal, Drury Lane, from The Microcosm of London (1808-10)

|

The royal command performance

Perdita and Florizel was well-received and the King commanded a royal performance which took place on 3 December 1779. The King’s eldest son,

George, Prince of Wales, accompanied his parents to the theatre. The royal box was very close to the stage and gave the 17-year-old Prince a close view of the actors on the stage and in the wings.

|

George IV

from Huish's Memoirs of her late

royal highness Charlotte Augusta (1818) |

George made flattering comments that were loud enough for Mary to hear whilst Mary performed her lines as if for the Prince alone. George was dazzled. The next morning, he declared to his confidante Mary Hamilton, one of the ladies in waiting at court, that he had fallen madly in love with Mary Robinson.

Florizel in love

Adopting the name Florizel, the Prince started a passionate correspondence with ‘Perdita’. His friend, George Capel, Viscount Malden, acted as messenger, urging Mary to meet the Prince. Mary wrote back, encouraging the Prince to be patient and offering sisterly advice.

|

| Writing table at Hampton Court Palace |

Although for many months, George’s affair with Mary was no more than a passionate correspondence, the press was quick to comment on their relationship.

In order to quash this unfavourable publicity and comply with the Prince’s wishes, Mary agreed to leave the theatre. On 31 May 1780, she gave her farewell performance, playing the cross-dressed part of Eliza/Sir Harry Revel in The Miniature Picture and Widow Brady in The Irish Widow.

|

Mrs Robinson - the celebrated Perdita

from The Memoirs of George IV by R Huish (1830) |

Reputation at risk

The Prince continued to push for a meeting. Mary knew that she was risking her entire reputation if she agreed. It was not until George enclosed a bond for £20,000 to be paid on his reaching his majority in one of his letters that Mary eventually agreed to an assignation.

George and Mary probably did not meet until as late as June 1780. The chosen venue was Kew, near to the house where the Prince lived with the Duke of York. Over the next few months, they met many times at

Kew, either in the gardens or at one of the servants’ houses or at the inn on nearby Eel Pie Island in the River Thames.

|

The Old Palace at Kew

from Memoirs of HM Sophia Charlotte of Mecklenburg Strelitz,

Queen of Great Britain, by WM Craig (1818) |

Celebrity status

Mary’s relationship with the Prince pushed her into the limelight even more than her acting career had done. People were interested in what she wore and where she went. She had become a Georgian celebrity!

The Prince established Mary in a house in Cork Street where she lavishly entertained him and his male friends. She wore a miniature of George around her neck and paraded around town in a variety of carriages. One carriage in particular was emblazoned with her initials encircled by a wreath of rosebuds which at a distance gave the appearance of a royal coronet.

|

Vauxhall by T Rowlandson

- Mary is on the right in a white dress with the Prince of Wales

at her side © British Museum |

The end of the affair

Mary continued to receive bad press. Cartoons were printed lampooning the Prince and his lover. There was outrage when Mary had dared to take a side box at the Opera House as if she was one of the nobility and not merely a courtesan. There was an unfortunate incident at Covent Garden where Mary flew into a rage on finding her husband with another woman. The King did not like all the bad publicity and wanted the affair finished, promising George his own establishment.

|

Opera House from The Microcosm of London (1808-10)

|

The Prince’s interest began to wane. The bad press was uncomfortable and George doubted Mary’s faithfulness to him. And with good cause; Mary was intimately involved with his friend, Lord Malden. By the end of 1780, Mary’s charms had been superseded by those of the courtesan, Elizabeth Armistead. All at once, it was over. Mary did not see it coming.

The price of a reputation

Mary was determined not to go quietly. She had been living expensively and had massive debts. The Prince’s desertion was disastrous. She had a large number of the Prince’s love letters which she threatened to publish, using them as leverage in negotiations to compensate her for the loss of her reputation and her career. Eventually Mary agreed to give up the letters in return for £5,000 and the promise of an annuity.

|

George IV coin (2012)

|

The papers continued to link their names together for years, perhaps encouraged by Mary’s persistence in wearing the Prince’s miniature, now encrusted with diamonds, around her neck.

It is a sad reflection that Mary Robinson, an acclaimed actress and later a feminist writer and poet, is remembered today for her brief affair with the Prince of Wales and not for her other achievements.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources used include:

Ackermann, Rudolph, and Pyne, William Henry, The Microcosm of London or London in miniature (1808-1810, reprinted 1904)

Byrne, Paula, Perdita, the life of Mary Robinson (2004)

Huish, Robert, Memoirs of George IV (1830)

Levy, Martin J, Robinson, Mary (Perdita) (1756/8-1800) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 2 July 2013)

Robinson, Mrs Mary, The Poetical Works of the late Mrs Mary Robinson: including many pieces never before published (1806)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net

No comments:

New comments are not allowed.