|

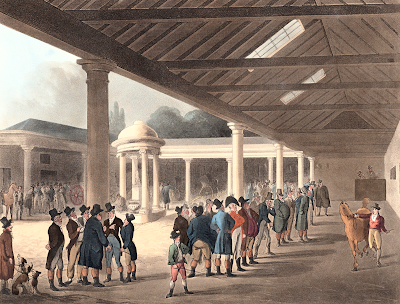

| The Mistletoe in Popular Pastimes by FW Stephanoff (1816) |

A Christmas tradition that romance authors love is kissing under the mistletoe.

But when did the tradition begin? Did young ladies of quality kiss under the mistletoe in the Regency? These are the questions I set out to answer in this blog.

What is mistletoe?

|

| Mistletoe decoration (2022) |

Mistletoe—sometimes spelt misletoe in old texts—is an evergreen plant with oval leaves that grow in pairs. It produces small white flowers, but is better known for its waxy, white berries which grow in clusters from October to May—right over the Christmas season.

It is an unusual plant because it is semi-parasitic. Rather than growing in the ground, it lives on the branches of other trees, such as apple, lime, pear, or oak.

Although all parts of the plant are poisonous, mistletoe is used in medicines to treat certain disorders like epilepsy and cancer.

When was mistletoe first associated with Christmas?

In pre-Christian Britain, mistletoe was connected with the winter solstice. The Druids revered the oak, and this reverence spread to everything connected with it—including mistletoe that grew on oak. It was revered for its healing properties and gathered in a ceremony steeped with superstition at the winter solstice.

When Christianity was established in Britain, new traditions developed. Stephanoff wrote in Popular Pastimes (1816):

The custom of decking our churches and habitations with evergreens, has existed from the very establishment of Christianity, and was unquestionably derived from the like similar practice of our Pagan ancestors.1

These evergreens included mistletoe, which is mentioned in Candlemas Eve, a poem written by Robert Herrick (1591–1674). He wrote about taking down the greenery, including mistletoe, on Candlemas Eve, signalling the end of the Christmas season:2

Down with the rosemary and bays,

Down with the mistletoe;

Instead of holly, now up-raise

The greener box, for show.3

Another early reference to mistletoe is in Art of Simpling, published in 1656. Coles wrote of mistletoe:

It is carryed many miles to set up in houses about Christmas time, when it is adorned with a white glistering berry.4

When did people first kiss under the mistletoe?

|

| Christmas Eve by J Burnett (1815) |

When at Christmas in the hall

The men and maids are hopping

If by chance I hear ‘em bawl,

Amongst ‘em quick I pop in.

When all the men, Jem, John, and Joe,

Cry, “What good luck has sent ye?”

And kiss beneath the mistletoe

The girl not turn’d of twenty.5

A poem quoted in Popular Pastimes (1816) is undated, but it hints at the possibility that the custom went back earlier:

The Misletoe hangs from an oaken beam,

The Ivy creeps up the outer wall;

The Bays our broken casements screen,

The Holly-bush graces the hall.

Then hey for our Christmas revelling,

For all its pastimes pleasures bring.

The Misletoe's berries are fair and white,

The Ivy's of gloomy sable hue;

Red as blood the Laurel's affect our sight,

And the Holly's the same with prickles too.

Then hey, & c.

Nor black nor ensanguined red for me: -

The Misletoe only is my delight:

For pure as love all its berries be,

And to kissing my Fanny's sweet lips invite.

Then hey for our Christmas revelling,

For thus its symbols pleasures bring.6

Upstairs or downstairs?

|

| Christmas Gambols by Thomas Rowlandson (1812) |

Mary Robinson’s poem, The Mistletoe – a Christmas Tale (1800) says:

‘Twas Christmas time, the peasant throng

Assembled gay, with dance and Song:

The Farmer's Kitchen long had been

Of annual sports the busy scene

…

It happen'd, that some sport to shew

The ceiling held a MISTLETOE.

A magic bough, and well design'd

To prove the coyest Maiden, kind.

A magic bough, which DRUIDS old

Its sacred mysteries enroll'd;

And which, or gossip Fame's a liar,

Still warms the soul with vivid fire;

Still promises a store of bliss

While bigots snatch their Idol's kiss.7

Observations on Popular Antiquities (1841) stated that mistletoe

…was the heathenish or profane plant, as having been of such distinction in the Pagan rites of Druidism, and it therefore had its place assigned it in kitchens.8

Stephanoff’s Popular Pastimes (1816) confirms this. He wrote mistletoe

…is still beheld with emotions of pleasurable interest, when hung up in our kitchens at Christmas; it gives licence to seize “the soft kiss” from the ruby lips of whatever female can be enticed or caught beneath. So custom authorizes, and it enjoins also, that one of the berries of the Misletoe be plucked off after every salute. Though coy in appearance, the “chariest maid” at this season of festivity is seldom loth to submit to the established usage; especially when the swain who tempts her is one whom she approves.9

Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (1836–7) suggests that though mistletoe was hung below stairs, the kissing was not restricted to the servants:

From the centre of the ceiling of this kitchen, old Wardle had just suspended, with his own hands, a huge branch of mistletoe, and this same branch of mistletoe instantaneously gave rise to a scene of general and most delightful struggling and confusion; in the midst of which, Mr Pickwick, with a gallantry that would have done honour to a descendant of Lady Tollimglower herself, took the old lady by the hand, led her beneath the mystic branch, and saluted her in all courtesy and decorum.

The old lady submitted to this piece of practical politeness with all the dignity which befitted so important and serious a solemnity, but the younger ladies, not being so thoroughly imbued with a superstitious veneration for the custom, or imagining that the value of a salute is very much enhanced if it cost a little trouble to obtain it, screamed and struggled, and ran into corners, and threatened and remonstrated, and did everything but leave the room, until some of the less adventurous gentlemen were on the point of desisting, when they all at once found it useless to resist any longer, and submitted to be kissed with a good grace.

Mr Winkle kissed the young lady with the black eyes, and Mr Snodgrass kissed Emily; and Mr Weller, not being particular about the form of being under the mistletoe, kissed Emma and the other female servants, just as he caught them. As to the poor relations, they kissed everybody, not even excepting the plainer portions of the young lady visitors, who, in their excessive confusion, ran right under the mistletoe, as soon as it was hung up, without knowing it!10

|

| Christmas Eve at Mr Wardle's by Phiz from Pickwick Papers by Charles Dickens (1836-7) |

I’ve not found a definitive answer to this one, although I’ve read multiple times of a superstition that it was bad luck to decorate the house before Christmas Eve. I’ve not found any contemporary evidence as yet to support this, but it is possible that the church discouraged people from decorating before the winter solstice (21 December) to separate the Christian festival of Christmas from the pagan celebration of the solstice.

Also, as Christmas Day was the start of the Christmas festivities, decorating on Christmas Eve would make sense. In the excerpt above from Pickwick Papers, this scene took place on Christmas Eve.

When was mistletoe taken down?

Another superstition I’ve come across is that it was bad luck to leave greenery up after Twelfth Night (5 January). Traditionally, greenery was taken down on Candlemas Eve (2 February) but at some point this changed to Twelfth Night.

Some sources suggest the lower classes were keen to keep the celebrations going and clung onto Candlemas as the end of the festivities for as long as possible.

What was a kissing bough?

|

| The Mistletoe Bough by F Wheatley (c1790) |

According to the English Heritage website, a kissing bough comprised two intersecting circles of greenery. It says:

It is not certain when kissing boughs were first introduced in England although they are often considered to have been a popular Christmas decoration in the Tudor period.11

A kissing bough was hung on a wall or from a ceiling or in a doorway near the entrance of the house to welcome visitors. Visitors embraced the master and mistress of the house under the kissing bough as a sign of goodwill.

I’ve come across various other names for a kissing bough, though it’s unclear whether these were all the same: a kissing ball, a Christmas bough, a mistletoe bough or a holy bough, with a clay figure of the baby Jesus in the middle.

Other sources suggest a kissing bough was the top part of a tree, hung upside down as a symbol of the Holy Trinity.

The inclusion of mistletoe in a kissing bough may have given rise to the tradition of kissing under the mistletoe.

In John Leech’s illustration of Mr Fezziwig’s Christmas party in A Christmas Carol (below), there appears to be a kissing bough hanging from the ceiling as well as mistletoe being held by hand over a girl’s head.

|

| Mr Fezziwig's Ball by John Leech from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens (1920 reprint of original 1843 edition) |

There seems to be some debate whether mistletoe was used to decorate churches or not.

John Gay (1685–1732) wrote in his poem The Approach of Christmas:

When Rosemary and Bays, the poet's crown,

Are bawled in frequent cries through all the town;

Then judge the festival of Christmas near,

Christmas, the joyous period of the year!

Now with bright Holly all the temples strew,

With Laurel green, and sacred MISLETOE.12

This seems to imply that all these evergreens were used to decorate churches at Christmas.

Observations on Popular Antiquities (1841) disagreed, stating that mistletoe

…never entered those sacred edifices, but by mistake or ignorance of the sextons.13

However, Popular Pastimes quoted Dr Stukeley as saying that the druids had a custom of laying mistletoe, which they called “All-heal”, on their altars, and that this custom still continued in the north, at York Minster.

Stephanoff added:

We learn that it [mistletoe] is still suffered to be put up (without scruple by the incumbent) in many of our churches at Christmas, where it remains with the other evergreens, till Candlemas-day.14

You can read more about Regency Christmas celebrations here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

- Stephanoff, Francis William, Popular Pastimes, Being a Selection of Picturesque Representations of the Customs & Amusements of Great Britain, in Ancient and Modern Times: Accompanied with Historical Descriptions (1816).

- Candlemas is on 2 February—40 days after Christmas—and celebrates the day Mary was purified according to Jewish law after giving birth to Jesus.

- Vizetelly, Henry, Christmas with the poets (1851).

- Quoted in Brand, John, & Ellis, Henry, Observations on Popular Antiquities (1841).

- Arnold, Dr, Two to One, a comic opera (1784).

- Stephanoff op cit.

- Robinson, Mary, The Mistletoe - a Christmas tale (1800).

- Brand & Ellis op cit.

- Stephanoff op cit.

- Dickens, Charles, The Pickwick Papers (1836-7).

- English Heritage website

- Vizetelly op cit.

- Brand & Ellis op cit.

- Stephanoff op cit.

Sources used include:

Arnold, Dr, Two to One, a comic opera (1784)

Brand, John, & Ellis, Henry, Observations on Popular Antiquities (1841)

Dickens, Charles, A Christmas Carol (1843)

Dickens, Charles, The Pickwick Papers (1836-7)

Hone, William, The Everyday Book (1826)

Newcomb, G, History of the Christmas Festival (1843)

Robinson, Mary, Lyrical Tales including The Mistletoe - a Christmas tale (1800)

Stephanoff, Francis William, Popular Pastimes, Being a Selection of Picturesque Representations of the Customs & Amusements of Great Britain, in Ancient and Modern Times: Accompanied with Historical Descriptions (1816)

The Kaleidoscope: or, Literary and scientific mirror (1821)

The New Monthly Magazine and Universal Register (1817)

Vizetelly, Henry, Christmas with the poets (1851)

English Heritage website on Tudor Christmas decorations

English Heritage website on Christmas greenery

Photograph © Rachel Knowles regencyhistory.net