|

| Pen and ink stand from A La Ronde, Exmouth |

What is a bluestocking?

According to the Chambers dictionary, a bluestocking is an intellectual woman. In the second half of the 18th century, the term referred to the men and women who attended the literary assemblies of the bluestocking circle or society, but it subsequently came to mean a lady of learning and was often applied in a derogative way, suggesting that too much knowledge was unfeminine.

|

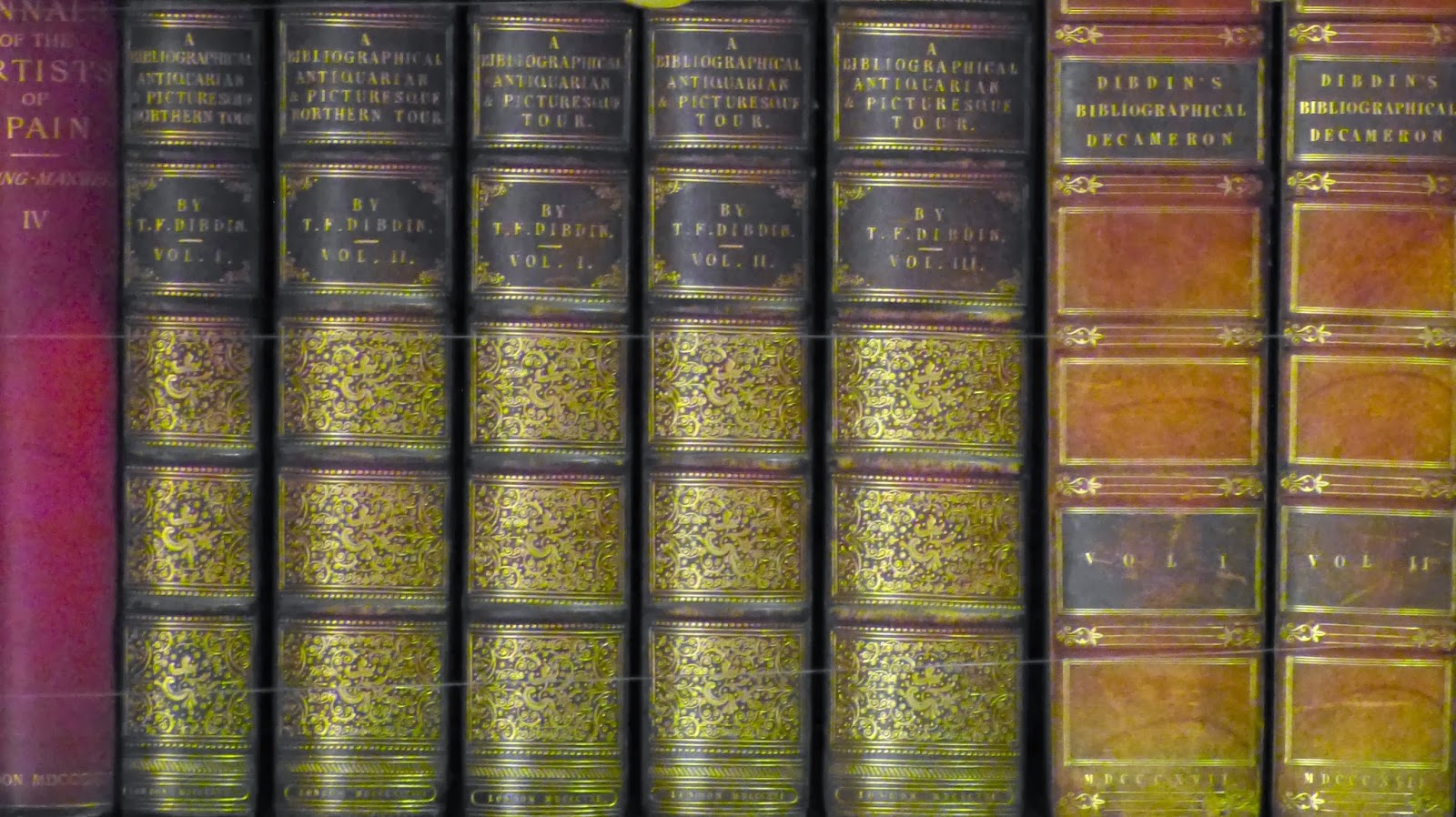

| Books on the shelves at Knightshayes, Devon |

The bluestocking circle

In the 1750s, a number of wealthy, intellectual women started to hold literary parties at their London houses. Although the bluestocking gatherings were hosted by women, they were open to people of both sexes and drew together people from different backgrounds. Their aim was to provide a setting where women could expand their knowledge by conversing freely with other women and men of learning.

James Boswell stated that...

it was much the fashion for several ladies to have evening assemblies, where the fair sex might participate in conversation with literary and ingenious men, animated by a desire to please. These societies were denominated Bluestocking Clubs.1

|

James Boswell from The Life of Samuel

Johnson by J Boswell (1851 edition) |

The bluestocking assemblies challenged the fashion of the day, offering stimulating conversation rather than cards or dancing, and tea rather than alcohol to drink. They were influenced by the French salons which were famous for their conversation, but unlike the French salons, they were unconnected with the court and insisted on high moral behaviour.

The bluestocking hostesses

Three of the most prominent bluestocking hostesses were

Elizabeth Montagu, Elizabeth Vesey and

Frances Boscawen. These wealthy, well-connected women held literary salons in their homes in London: Elizabeth Montagu in Hill Street and later in Portman Square; Elizabeth Vesey in Clarges Street; and Frances Boscawen in South Audley Street.

The hostesses vied with each other to offer the most distinguished company. According to Taylor:

Mrs Montagu bore away the bell, thanks as much to her name, her diamonds, her dinners, and her determination, as to her agreeableness or learning.2

Samuel Johnson dubbed Mrs Montagu “Queen of the Blues”.

|

Elizabeth Montagu

from The Letters of Mrs Elizabeth Montagu (1810) |

Mrs Montagu seated her guests in a large semi-circle in order to encourage a unified discussion whilst Mrs Vesey favoured more random, scattered groups, sometimes even placing chairs back to back.

The bluestockings

The bluestocking assemblies drew together a wide range of people – artists and writers, botanists and politicians, actors and musicians.

The bluestocking circle included Hester Thrale;

Hannah More; Hester Chapone; Mary Delany; Margaret Bentinck, Duchess of Portland; Elizabeth Carter;

Sir Joshua Reynolds and his sister Frances;

Fanny Burney; Samuel Johnson; William Pulteney, 1st Earl of Bath; James Boswell; David and Eva Garrick; Edmund Burke; George Lyttelton; Mrs Ord; Mrs Crewe and Benjamin Stillingfleet.

|

Elizabeth Carter from Memoirs of the Life

of Elizabeth Carter by Rev M Pennington (1816) |

Where did the term bluestocking come from?

The term bluestocking is said to derive from a story regarding Benjamin Stillingfleet, a botanist and author, who attended the bluestocking assemblies.

Boswell wrote that:

One of the most eminent members of those societies, when they first commenced, was Mr Stillingfleet, whose dress was remarkably grave, and in particular it was observed that he wore blue stockings. Such was the excellence of his conversation, that his absence was felt as so great a loss, that it used to be said, ‘We can do nothing without the blue stockings’ and thus by degrees the title was established.1

|

Benjamin Stillingfleet from Literary life

and selected works of Benjamin Stillingfleet (1811) |

The blue stockings referred to were blue worsted stockings, everyday rather than evening wear. The implication was that conversation was more important than fashion and informal dress was acceptable.

Taylor wrote a slightly different account, that Mrs Vesey had invited Stillingfleet to an assembly and cut short his excuses on account of his dress by saying ‘Pooh, pooh! Come in your blue stockings.’2

Taylor also suggested an alternative source for the term. He quoted Mrs Crewe, another of the bluestockings, as saying that it arose from Madame de Polignac appearing at one of Mrs Montagu’s assemblies in her blue silk stockings which were fashionable in Paris.2

The bluestocking influence

The bluestockings were active in philanthropy and advocated the provision of education. They patronised new talent and encouraged women to go into publication who might otherwise not have done so. Hannah More was the most widely published and encouraged other women by her example.

Despite its seemingly forward-thinking promotion of women’s education, the bluestocking circle was conservative in its views towards society and religion. When Hester Thrale married Gabriel Piozzi, an Italian musician, her fellow bluestockings reacted very negatively.

|

Hester Thrale Piozzi from Autobiography Letters

and Literary Remains of Mrs Piozzi (Thrale) (1861) |

Le bas bleu

In 1786, Hannah More published a poem, Le bas bleu, in defence of the bluestockings. The poem praised the bluestocking assemblies and attempted to show that conversation was more desirable than fashionable pursuits.

|

Hannah More

from Memoirs of the life and correspondence

of Mrs Hannah More by William Roberts (1835) |

The decline of the bluestocking circle

The bluestocking circle was at its peak between 1770 and 1785. After this time, the bluestocking influence began to decline. In 1785, Elizabeth Vesey’s husband died, leaving her in relative poverty. With failing health, she closed her home, dying in 1791. Elizabeth Montagu died in 1800 and Frances Boscawen in 1805.

In addition, the French revolution ushered in a time of greater conservatism. Learning in women was ridiculed by some influential writers, such as William Hazlitt, and bluestocking became a term of derision applied to women who were considered too learned to be marriageable.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

1. The Life of Samuel Johnson by James Boswell (1791).

2. Life and Times of Sir Joshua Reynolds by Robert Leslie and Tom Taylor (1865).

Sources used include:

Boswell, James, The Life of Samuel Johnson LL.D, with new additions by John Wilson Croker (1851 edition)

Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett (1846)

Eger, Elizabeth, Bluestocking circle (c1755-c1795), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, online edn Jan 2012, accessed 7 June 2012)

Leslie, Charles Robert, RA, and Taylor, Tom, MA, Life and Times of Sir Joshua Reynolds (1865)

McCalman, Iain (ed), Bluestockings, An Oxford Companion to the Romantic Age (OUP 2009 Oxford Reference Online, accessed 14 November 2011)

Schnorrenberg, Barbara Brandon, Montagu, Elizabeth (1718-1800) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004, online edn May 2009, accessed 7 June 2012)

Stillingfleet, Benjamin, Literary life and select works of Benjamin Stillingfleet, ed W Coxe (1811)

Thrale, Hester, Autobiography Letters and Literary Remains of Mrs Piozzi (Thrale) edited by A Hayward (1861)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net