Naming a royal baby is a huge responsibility. Other parents can choose whatever names they like, but William and Kate have to select those that are suitable for a future monarch and meet the approval of the royal family.

So what advice would the Georgian royals have given to William and Kate?

The nine sons of George III

George III and

Queen Charlotte had fifteen children. The eldest was born “at twenty-four minutes past seven” on 12 August 1762 after a hard labour. Lord Huntingdon, the Groom of the Stole, pre-empted the Queen’s Vice-Chamberlain and announced to the King that the Queen had given birth to a baby girl.

|

Queen Charlotte

from Memoirs of her most

excellent majesty Sophia-Charlotte

Queen of Great Britain

by John Watkins (1819) |

The King replied that he was “but little anxious as to the sex of the child” so long as the Queen was safe. It was just as well. The Queen had, in fact, given birth to a “strong, large and pretty boy”! The baby was christened George Augustus Frederick – the names of his father and his paternal grandparents, Augusta and Frederick. After his father’s death, he became King

George IV.

George III’s other sons were named

Frederick,

William Henry,

Edward Augustus,

Ernest Augustus,

Augustus Frederick,

Adolphus Frederick,

Octavius and

Alfred. Clearly George III was very fond of the name Augustus.

The five daughters of George III

George III’s first daughter, born on 29 September 1766, was similarly given family names. She

was christened

Charlotte Augusta Matilda – the names of her mother, her paternal grandmother and her aunt, George III’s youngest sister. But Princess Charlotte did not get to use her names; she was always referred to by her title, Princess Royal.

George III’s other daughters were named

Augusta Sophia,

Elizabeth,

Mary,

Sophia and

Amelia. Note the recurrence of Augusta – the second name of the Princess Royal and the first of her next youngest sister.

George III’s advice for William and Kate

|

George III

from Memoirs of Queen Charlotte

by WC Oulton (1819) |

For a boy, William Charles Augustus – for the child’s father and grandfather and because George really liked the name Augustus.

For a girl, Catherine Charlotte Diana Augusta – for the child’s mother, father and grandmother and because George really liked the name Augusta.

The birth of Princess Charlotte Augusta

|

Princess Charlotte

from La Belle Assemblée (1816) |

The marriage of the future George IV to his cousin

Caroline of Brunswick was a complete disaster. Amazingly, in the short time that they lived together before their separation, Caroline conceived. George stayed up for two whole nights waiting for news of the birth. On 7 January 1796 he was able to tell the Queen: “The Princess, after a terrible hard labour for above twelve hours, is this instant brought to bed of an immense girl, and I assure you notwithstanding we might have wished for a boy, I receive her with all the affection possible.”

The new baby was not given her hated mother’s name, but was christened

Charlotte Augusta, the names of her two grandmothers.

George IV’s advice to William and Kate

|

George, Prince of Wales

from Memoirs of her late

royal highness Charlotte Augusta

by Robert Huish (1818) |

For a boy: George William – for himself and the child’s father - George liked himself too much to choose anyone else’s name above his own!

For a girl: Elizabeth Mary – for the child’s great grandmother and George’s favourite sister. He would not use the child’s mother’s name because he hated his own wife and would not use her grandmother’s name because it would remind him of his own failed marriage.

The birth of Queen Victoria

After the death of Princess Charlotte, the race was on to provide an heir to the throne. In 1819, the Dukes of Cumberland and Cambridge both had sons whom they named George, but the child of the Duke of Kent stood before them in line for the throne. On 24 May 1819, a daughter was born to the Duke of Kent and his wife, Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg-Saalfeld.

|

Queen Victoria

by Dalton after F Winterhalter

from The Girlhood of Queen Victoria (1912) |

The Duke and Duchess of Kent proposed to name their daughter Victoire or Victoria after her mother, Georgiana after the Regent, Alexandrina after the Tsar and Charlotte and Augusta, after her aunts, or possibly after her grandmother and great grandmother. As a matter of form, they submitted the names to the Regent for approval. George chose to be difficult. He declared that he did not like to put his own name before the Tsar’s, but neither did he wish it to appear after it. He would not countenance the baby being given the name of his poor dead daughter and decreed that Augusta was “too majestic”.

When the christening service began, nobody knew what the baby was to be named. The Regent stated that the baby was to be called Alexandrina; the Duke of Kent proposed Elizabeth. The Regent dismissed that suggestion and finally agreed to the baby receiving her mother’s name, though he insisted that it had to follow the name of Tsar. So the baby was named Alexandrina Victoria and as a small girl, she was often called Drina.

The Duchess of Kent’s mother wrote to her daughter that she hoped she was happy with a girl. “The English like Queens,” she wrote. The Duke of Kent was delighted and proudly showed her off, telling people to “look at her well, for she will be Queen of England.” And he was right.

The Duke of Kent’s advice to William and Kate

|

Edward, Duke of Kent

from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick,

Duke of York and Albany

by John Watkins (1827) |

For a boy: William Charles – for the child’s father and grandfather.

For a girl: Catherine Diana Elizabeth – for the child’s mother and grandmother and great grandmother, the Queen.

What names do you think the Georgians would have chosen?

My choice? William Charles Augustus for a boy and Charlotte Catherine Diana for a girl.

Postscript

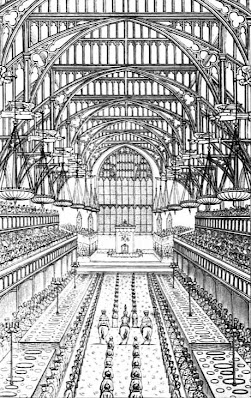

The Duke and Duchess of Cambridge's first baby was a boy and has been named George Alexander Louis. George IV would have approved. The christening is to be held on Wednesday 23 October at 3pm in the Chapel Royal in St James' Palace.

|

St James' Palace

from Leigh's New Picture of London (1827) |

Sources used include:

Hibbert, Christopher,

George III (1998, Viking, Great Britain)

Hibbert, Christopher,

George IV (1972, Longmans, 1973, Allen Lane, London)

Hibbert, Christopher,

Queen Victoria (HarperCollins, 2000, London)

Huish, Robert,

Memoirs of her late royal highness Charlotte Augusta (1818)

Oulton, Walley Chamberlain,

Authentic and Impartial Memoirs of Her Late Majesty Charlotte, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (1819, London)

Victoria, Queen,

The Girlhood of Queen Victoria, A Selection from Her Majesty's Diaries between the years 1832 and 1840, edited Viscount Esher 2 Volumes (1912)

Watkins, John,

A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1827, London)