|

| Kensington Palace (2017) |

Kensington Palace is situated in Kensington Gardens in London.

History

Kensington Palace started life as a Jacobean mansion built around 1605. It was bought by William III and Mary II in 1689 and was transformed into a royal palace by Sir Christopher Wren so that the King and Queen could live away from the London air.

The palace is now in the care of Historic Royal Palaces.

Georgian connections

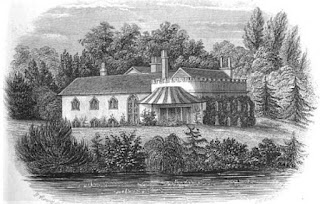

|

| Kensington Palace from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

Neither George III, George IV nor William IV chose to live at Kensington Palace. They granted “Grace and Favour” apartments to courtiers and members of the royal family. These included:

- George IV's estranged wife, Caroline, Princess of Wales

- Princess Sophia

- Augustus, Duke of Sussex

- Queen Victoria's father, Edward, Duke of Kent

|

| Kensington Palace through the Gold Gates (2017) |

|

| Kensington Palace from Kensington Gardens (2017) |

Visiting royal palaces is not a new entertainment. Although not opened to the public until 1899, it was possible to see inside Kensington Palace during the Regency period.

According to Feltham's Picture of London for 1818:

The palace is a large and splendid edifice of brick, and has a set of very handsome state apartments, and some beautiful staircases and ceilings, painted by Verrio and others. He continued: The whole may be seen any day except Sundays, by applying to the housekeeper, for a trifling douceur.1The State Apartments

The King's Staircase

|

| The King's Staircase, Kensington Palace (2012) |

|

| The Great Staircase, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| Queen Caroline's Drawing Room, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The Queen's Bedchamber, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The Queen's Dining Room, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The Queen's Gallery, Kensington Palace (2017) |

|

| The Queen's Gallery, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The Prescence Chamber, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The Admirals' Gallery, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The Cupola Room, Kensington Palace (2017) |

|

| The ceiling of the Cupola Room, Kensington Palace (2017) |

|

| The Cupola Room, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The King's Drawing Room, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| Learning to play Hazard in the King's Drawing Room, Kensington Palace (2017) |

|

| The King's Closet, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

Queen Caroline's Closet

|

| Queen Caroline's Closet, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

|

| The King's Gallery, Kensington Palace (2017) |

|

| The King's Gallery, Kensington Palace, from The History of the Royal Residences by WH Pyne (1819) |

Queen Victoria was born in Kensington Palace on 24 May 1819. It is believed that she was born in the North Drawing Room of her parents’ apartments.

|

| Room where Queen Victoria was born , Kensington Palace (2014) |

Victoria’s father, Edward, Duke of Kent, died suddenly less than a year after her birth, and Victoria and her mother were left virtually penniless. They returned to their apartments at Kensington Palace where Victoria was brought up in relative seclusion.

When William IV visited the palace in August 1836, he discovered that the Duchess of Kent had adopted some of the state rooms and altered them to suit herself. William was furious and publicly complained about the liberties his sister-in-law had taken and announced his wish that he would live long enough for Victoria to reach her 18th birthday, thereby preventing the Duchess from becoming regent. His wish was granted; he died just four weeks after Victoria turned 18.

If you enjoyed this article, you might also enjoy my guides to Kensington Gardens and Kew Palace.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Note

1. From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Sources used:

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Humphrys, Julian, The private life of palaces (Historic Royal Palaces, 2006)

Pyne, WH, The history of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House and Frogmore (1819)

Kensington Palace official website

Photographs © RegencyHistory.net

1. From Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Sources used:

Feltham, John, The Picture of London for 1818 (1818)

Humphrys, Julian, The private life of palaces (Historic Royal Palaces, 2006)

Pyne, WH, The history of the Royal Residences of Windsor Castle, St James's Palace, Carlton House, Kensington Palace, Hampton Court, Buckingham House and Frogmore (1819)

Kensington Palace official website

Photographs © RegencyHistory.net