Mary Robinson (27 November 1757 – 26 December 1800) was an actress and author, famous for being the first mistress of the young George IV.

Family background

Mary Darby was born in Bristol on 27 November 1757, the daughter of Nicholas Darby, a merchant sailor, and his wife Hester, who was thought to have married beneath her.1 Mary had two brothers, John and George, who survived into adulthood.

Mary was educated in Bristol, at a school run by Hannah More and her sisters. In 1765, Darby left to try to establish fisheries on the Labrador coast. The enterprise failed and they were forced to sell the family home. Mary’s parents separated and Mary went to live in London with her mother.

Marriage or the stage

Mary was introduced to David Garrick who coached her for the stage. But before Mary’s theatrical career could get started, she was persuaded to marry Thomas Robinson, an articled clerk with good prospects. Robinson and Mary were married on 12 April 1773, but it soon transpired that Robinson had lied and his future prospects had been grossly exaggerated. He proved to be an unreliable and unfaithful husband.

Family background

Mary Darby was born in Bristol on 27 November 1757, the daughter of Nicholas Darby, a merchant sailor, and his wife Hester, who was thought to have married beneath her.1 Mary had two brothers, John and George, who survived into adulthood.

Mary was educated in Bristol, at a school run by Hannah More and her sisters. In 1765, Darby left to try to establish fisheries on the Labrador coast. The enterprise failed and they were forced to sell the family home. Mary’s parents separated and Mary went to live in London with her mother.

Marriage or the stage

Mary was introduced to David Garrick who coached her for the stage. But before Mary’s theatrical career could get started, she was persuaded to marry Thomas Robinson, an articled clerk with good prospects. Robinson and Mary were married on 12 April 1773, but it soon transpired that Robinson had lied and his future prospects had been grossly exaggerated. He proved to be an unreliable and unfaithful husband.

On 18 October 1774, Mary gave birth to a daughter, Maria Elizabeth, who was Mary’s constant companion for the rest of her life – her “adored and affectionate secondself”. A second daughter, Sophia, was born in May 1777, but died from convulsions as a baby.

Money problems

The Robinsons lived beyond their means and in May 1775, Robinson was arrested for debt. Mary and baby Maria spent 15 months in the Fleet Prison with him.

|

| The Fleet Prison, from The Microcosm of London (1808-10) |

Desperate for money, Robinson agreed that Mary should go on stage. She was engaged by Richard Brinsley Sheridan at the Drury Lane Theatre and Garrick loyally came out of retirement to coach her for the part of Juliet. On 10 December 1776, she gave her first performance and was an instant success.

Perdita and Florizel

Mary was very attractive with curly, dark auburn hair and soft blue eyes. George, Prince of Wales, became obsessed with her after seeing her in the role of Perdita in Florizel and Perdita, on 3 December 1779. The Prince embarked on a passionate correspondence, styling himself as Florizel to Mary’s Perdita.

Perdita and Florizel

Mary was very attractive with curly, dark auburn hair and soft blue eyes. George, Prince of Wales, became obsessed with her after seeing her in the role of Perdita in Florizel and Perdita, on 3 December 1779. The Prince embarked on a passionate correspondence, styling himself as Florizel to Mary’s Perdita.

|

| George, Prince of Wales, later George IV by Hoppner © The Wallace Collection |

George and Mary became lovers after he gave her a bond for £20,000 to be paid on his majority. At the Prince’s urging and to help reduce the bad press they were getting, Mary gave up her career, performing for the last time on 31 May 1780. But by the end of the year, the affair was over. The fickle Prince had transferred his affections to the courtesan, Elizabeth Armistead.

Mary was deeply in debt and accepted £5,000 and the promise of an annuity in exchange for the Prince’s love letters.

Fashion leader

Mary’s relationship with the Prince pushed her to the forefront of the fashionable world. She introduced new styles from Paris and English designs were named for her, such as the Perdita – “a chip hat with a bow and pink ribbons puff’d round the crown” in spring 1781.2 Mary was also famous for her smart carriages.

Whig supporter

Mary was an ardent Whig and supporter of Charles James Fox, both on the streets like the Duchess of Devonshire, campaigning for the Whigs in the 1784 general election, and through her poetry.

Fashion leader

Mary’s relationship with the Prince pushed her to the forefront of the fashionable world. She introduced new styles from Paris and English designs were named for her, such as the Perdita – “a chip hat with a bow and pink ribbons puff’d round the crown” in spring 1781.2 Mary was also famous for her smart carriages.

Whig supporter

Mary was an ardent Whig and supporter of Charles James Fox, both on the streets like the Duchess of Devonshire, campaigning for the Whigs in the 1784 general election, and through her poetry.

|

| Charles James Fox from The Historical and Posthumous Memoirs of Sir Nathaniel Wraxall (1884) |

Mary was continually propositioned by gentlemen including Lord Lyttelton and George Fitzgerald, who Mary claimed tried to abduct her from Vauxhall. As well as the Prince, Mary’s name was linked with several other prominent figures including Viscount Malden, the Duke of Lauzun, Charles James Fox and Colonel Banastre Tarleton.

Colonel Banastre Tarleton

|

| Lieutenant Colonel Banastre Tarleton Print by M Rosenthal after C Blackberd (1885) © British Museum |

Mary’s most enduring relationship was with Colonel Banastre Tarleton, the love of her life, which lasted, on and off, from 1782 until 1797. Their affair was passionate but stormy. Tarleton was expensive and a gambler and they were always short of money.

In 1783, Mary became pregnant with Tarleton’s child. Fearing that he was deserting her and fleeing the country to escape his debts, Mary pursued him through the night. As a result, she lost her baby and became extremely ill with a rheumatic fever which left her lame for the rest of her life.3

This time, she and Tarleton were reunited, but in 1797, he left her permanently and afterwards married Susan Bertie, an heiress of £20,000.

In 1783, Mary became pregnant with Tarleton’s child. Fearing that he was deserting her and fleeing the country to escape his debts, Mary pursued him through the night. As a result, she lost her baby and became extremely ill with a rheumatic fever which left her lame for the rest of her life.3

This time, she and Tarleton were reunited, but in 1797, he left her permanently and afterwards married Susan Bertie, an heiress of £20,000.

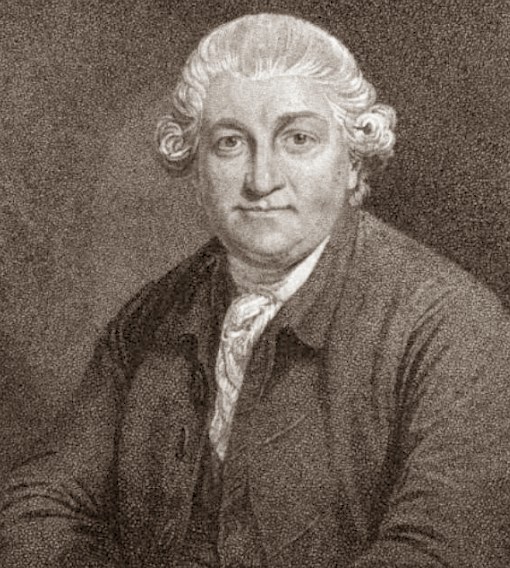

|

| Mary Robinson from an engraving by Smith after Romney in Memoirs of Mary Robinson (1895) |

Mary’s illness forced her to adopt a new way of life. Back in 1775, she had published a book of her poems and gained the patronage of the Duchess of Devonshire. Now she dedicated herself to writing.

Mary wrote profusely. She published more volumes of her poetry and wrote for different publications, such as The World, The Oracle and The Morning Post, using pseudonyms, such as Laura, Tabitha Bramble and The Sylphid, as well as her own name. She published several novels with feminist undertones and a feminist essay. She also wrote two plays and an opera, but these were not successful.

Mary also composed her Memoirs.4 Although they were predisposed in her own favour, they nevertheless represent an early instance of an English writer’s autobiography.

Friends

Mary inspired devoted friendships. Amongst her close friends and supporters were Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Mary wrote profusely. She published more volumes of her poetry and wrote for different publications, such as The World, The Oracle and The Morning Post, using pseudonyms, such as Laura, Tabitha Bramble and The Sylphid, as well as her own name. She published several novels with feminist undertones and a feminist essay. She also wrote two plays and an opera, but these were not successful.

Mary also composed her Memoirs.4 Although they were predisposed in her own favour, they nevertheless represent an early instance of an English writer’s autobiography.

Friends

Mary inspired devoted friendships. Amongst her close friends and supporters were Sir Joshua Reynolds, David Garrick, William Godwin, Mary Wollstonecraft and Samuel Taylor Coleridge.

Despite her diligence, Mary’s income was low and her expenses high. Her lameness necessitated keeping a carriage and payment of the annuities from the Prince and Lord Malden were erratic. In 1800 she was arrested for debt but released soon after.

Illness and death

Mary struggled with poor health for the rest of her life and visited Bath, Brighton and continental health resorts in search of some amelioration for her sufferings. She lived at Englefield Cottage, in Old Windsor, with her daughter, where she still entertained a small group of intimate friends.

Mary died on 26 December 1800 and was buried in Old Windsor churchyard. Only two people attended the funeral: the satirist, John Wolcot, (who used the pseudonym ‘Peter Pindar’) and William Godwin.

Illness and death

Mary struggled with poor health for the rest of her life and visited Bath, Brighton and continental health resorts in search of some amelioration for her sufferings. She lived at Englefield Cottage, in Old Windsor, with her daughter, where she still entertained a small group of intimate friends.

Mary died on 26 December 1800 and was buried in Old Windsor churchyard. Only two people attended the funeral: the satirist, John Wolcot, (who used the pseudonym ‘Peter Pindar’) and William Godwin.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) There is some confusion over Mary’s birth year. Her gravestone and the printed version of her Memoirs state her birth date as 27 November 1758. However, there is a baptismal record in the church of St Augustine the Less in Bristol of a Polly Derby on 19 July 1758. If this was indeed Mary’s baptism, then she must have been born the year before, in 1757. In her Memoirs, Mary stated that she was married at the age of 15. This supports a birth year of 1757.

(2) From The Lady’s Magazine (1781).

(3) Martin Levy in his article for the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography wrote that Mary had a paralytic stroke at this time and suffered from rheumatism later in life.

(4) Memoirs of the Late Mrs Robinson written by herself were published posthumously by her daughter in 1801.

Sources used include:

Byrne, Paula, Perdita, the life of Mary Robinson (2004)

Davies, Thomas, Memoirs of the Life of David Garrick (1808)

Levy, Martin J, Robinson, Mary (Perdita) (1756/8-1800) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 2 July 2013)

Robinson, Mary, Memoirs of Mary Robinson "Perdita" from the edition edited by her daughter with intro & notes by J Fitzgerald Molloy (1895)

Robinson, Mrs Mary, The Poetical Works of the late Mrs Mary Robinson: including many pieces never before published (1806)

Byrne, Paula, Perdita, the life of Mary Robinson (2004)

Davies, Thomas, Memoirs of the Life of David Garrick (1808)

Levy, Martin J, Robinson, Mary (Perdita) (1756/8-1800) Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2008, accessed 2 July 2013)

Robinson, Mary, Memoirs of Mary Robinson "Perdita" from the edition edited by her daughter with intro & notes by J Fitzgerald Molloy (1895)

Robinson, Mrs Mary, The Poetical Works of the late Mrs Mary Robinson: including many pieces never before published (1806)

All photographs © RegencyHistory.net

Another poor woman shamefully treated, but what happened to the £20.000 bond, did the prince renege on that?

ReplyDeleteMary was desperate for money and accepted the £5000 in return for the letters. She tried to hold out for more, but when she realised she wasn't going to get it, I guess she just accepted that £5K now was a lot better than nothing or even the promise of the £20K later which I don't suppose would have been enforceable as the Prince was under age when he gave it.

DeleteTarleton was a notorious supporter of the slave trade, and he has a street named after him in Liverpool, the chief slave-trading port. Does this show a degree of moral blindness on Mary's part?

ReplyDeleteWell, yes and no. Yes, in as much as she didn't interfere with Tarleton's politics. No, when it came to her own beliefs which became increasingly radical and opposed to Tarleton's. Her later works included some anti-slavery poems.

DeleteIs it true Mary often helped Tarleton write his parliamentary speeches (before the separation)?

DeletePossible, but I'm afraid I don't know.

DeleteAnne, you're looking at the situation from today's point of view.There were a number of enlightened souls at that time who opposed slavery but it was generally accepted by many others. I understand that there are several statues of the genocide Cromwell in the UK, even now, streets named after him and there is actually a portrait of him in Parliament, which to my mind is far less excusable.

ReplyDelete