|

| Nostell Priory |

An introduction to Georgian architecture

The reigns of George I through to

George IV are characterised by a distinctive form of building design and decoration. The symmetry and simplicity of Georgian architecture has become a symbol of British restrained good taste, and indeed of 'Britishness' itself.

This short guide is an introduction to what is a huge subject.

Early Georgian architecture

Importing a new monarchy from Hanover to Britain in 1714 represented a major break with the past. The optimistic, forward-looking spirit of the age was reflected in the adoption of a new architecture for the nation's buildings.

This change meant putting aside the Baroque, which peaked in

St Paul’s Cathedral, Castle Howard and Blenheim Palace. It was replaced by the Palladian style, based heavily on Roman antiquity and inspired by the works of Andrea Palladio (1508-1580).

|

Andrea Palladio

from The gallery of portraits with memoirs

by AT Malkin (1836) |

Two leading proponents of Palladian architecture in England were Lord Burlington (1694-1753) and William Kent (1685-1748). Burlington travelled to Italy to study Palladio’s work for himself. Here he met Kent, who became his assistant and spent much of his time designing sumptuous interior decoration.

|

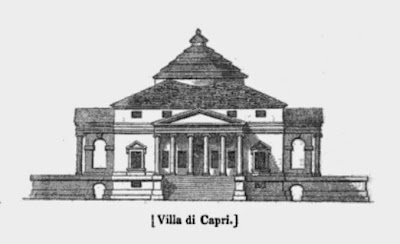

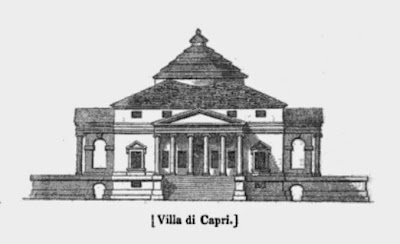

Palladio's Villa Capra or Villa Rotunda

from The gallery of portraits with memoirs

by AT Malkin (1836) |

The heyday of Palladianism was 1715 to 1760. Buildings of this style constructed in this period are often referred to as Neo-Palladian, to distinguish them from earlier uses of Palladian principles. Inigo Jones (1573-1652), who built the Banqueting House in Whitehall, was the first to apply the Palladian approach to British buildings, but the style fell from favour after the English Civil War.

|

The Pantheon,

- the inspiration for Palladio's Villa Capra |

Features of Palladian architecture

• Strict adherence to the rules of proportion. Palladio was heavily influenced by the writing of Roman architect Vitruvius, who believed there was a perfect symmetry and proportion in nature, which could be replicated in buildings. By studying the work of Vitruvius, and ruins of ancient buildings, Palladio created a set of architectural rules.

• Symmetry - one half of the building, or at least the façade, is a mirror image of the other.

• Columns topped with capitals carved into the shape of acanthus leaves, often referred to as Corinthian columns.

• Scallop shell motifs.

• Pediments over doors and windows - these are triangular, often containing some form of decoration.

|

| The entrance hall, Clandon Park |

True Palladian designs come over as heavy when compared to their Neoclassical successors.

Examples of Palladian architecture

• Chiswick House, West London, is usually regarded as the best example, being built by the leader in Palladian fashion, Lord Burlington, with interiors designed by William Kent.

|

| Clandon Park - rear view |

• Houghton Hall, Norfolk, built by Sir William Walpole, the first British Prime Minister, in the 1720s. The interiors were designed by William Kent.

Rebellion against the rules

Not everyone wants to be constrained, including architects.

Robert Adam (1728-92), from Kirkcaldy, Scotland, had no time for the restrictions imposed by the Palladian style and became an advocate of its successor, the Neoclassical.

While also rooted in the ancient world, Neoclassical design looked beyond Rome to include ideas from Greece. Archaeological curiosity and the advent of the

Grand Tour provided a wider perspective on classical cultures. Adam himself went on the Tour in 1754 and spent several years in Rome, studying architecture.

Features of Neoclassical architecture

Many of the features popular in Palladian architecture, such as symmetry, columns and pediments, also feature in the Neoclassical.

In general, Neoclassical style incorporates many more aspects of Ancient Greek art, such as cameos. Josiah Wedgwood, the famous Staffordshire potter, designed in the Neoclassical style.

Examples of Neoclassical architecture

• Kedleston Hall, Derbyshire, which Robert Adam worked on for around 20 years.

|

| Kedleston Hall |

•

Osterley Park, designed by Robert Adam and built by 1780.

•

Saltram House, again designed by Adam, who worked on it 1768-69.

|

| Saltram House |

What is the difference between Palladian and Neoclassical architecture?

At first glance, the building constructed in the Palladian style is very similar to a Neoclassical design. Both have pillars; both have symmetry; both have strong classical lines.

The date of construction might be a clue, with Palladian preceding Neoclassical, but there was a considerable period of overlap.

The biggest difference, which might be hard to spot, is that Palladian architecture adhered to the rules of proportion. Neoclassical architects, such as Robert Adam, made a conscious decision to break free of the restrictions these rules imposed. The results were lighter, more elegant constructions which, for many, represent the pinnacle of Georgian architectural achievement.

|

The Marble Hall, Kedleston Hall,

designed by Robert Adam |

An explosion of styles

The Georgians were not afraid to experiment and explore architectural alternatives to the classical form. The late eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries saw the emergence of Gothic revival and the

Regency style, while the incorporation of exotic ideas reached its zenith in the Brighton Pavilion.

|

| Brighton Pavilion |

Gothic revival

The Gothic style, firmly rooted in the medieval period, is celebrated in numerous churches and cathedrals across Britain. It made a resurgence in the late eighteenth century, most famously at

Strawberry Hill, built by writer Horace Walpole (1717-1797).

Here, in Twickenham, he built his “little Gothic castle”. Its battlements and towers rapidly became a tourist attraction, although he restricted entry to just four people per day, and no children. The popularity of the house, and the revived Gothic style, opened the way for the more significant Gothic revivals of the mid-nineteenth century.

|

| Gothic cottage, Stourhead |

The Regency style

The Georgian architectural legacy stretches far beyond grand houses and public buildings. Numerous towns and cities enjoy elegant rows of terraced houses built in what is now called the Regency Style.

|

| Part of Weymouth Esplanade |

Much of Bath, large swathes of London including Regent Street, the Esplanade in Weymouth - all these are surviving examples of the Regency Style. It began in Bath, where John Wood the Elder (1704-1754) combined the Palladian style with his own ideas on town planning.

The world-renowned Royal Crescent, probably the most photographed example of Georgian architecture, was built in 1767-1775 by John Wood the Younger, who continued the architectural vision of his father.

|

| Royal Crescent, Bath |

John Nash (1752-1835) took Wood’s ideas and applied them in his work for the Prince Regent, which began in earnest in 1810. His major project was the route linking Regent’s Park to Carlton House, a major exercise in town planning.

Brighton Pavilion

While the Georgian architecture of the eighteenth century was heavily influenced by classical Greek and Roman forms, the early nineteenth century began to absorb more exotic ideas.

|

| Brighton Pavilion |

These influences are exemplified in the extravagant display constructed by the Prince Regent in Brighton.

The Royal Pavilion, initially a farmhouse, then the

Neoclassical Marine Pavilion, became a curious mixture of Indian, Chinese, Tudor and Gothic styles. The domes and towers of the creation we see today are another example of the work of John Nash.

Georgian architecture in Britain reflected both the growing wealth of the nation and its increasing global reach. It also created a set of styles that are still popular with many today. Prince Charles famously holds strong views on building design and is constructing his own vision of a modern town at Poundbury in Dorset. The architecture is distinctly Neoclassical, literally building on the tradition established during the reign of his ancestor

George III.

|

| Poundbury, Dorset |

Rachel Knowles writes faith-based Regency romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew, who wrote this blog.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Sources used include:

Architectural Trust website

BBC website

Country Life website

Guardian website

Houghton Hall website

John Wood the Elder website

Strawberry Hill website

Suppes, Patrick, Rules of Proportion in Architecture (Stanford edu articles)

Telegraph website

V&A website: Gothic revival

V&A website: Neoclassicism

V&A website: Palladianism

All photographs by Andrew Knowles © regencyhistory.net