|

George Brummell

from The History of White's

by Hon Algernon Bourke (1892) |

Profile

George "Beau" Brummell (7 June 1778 - 30 March 1840) was a Regency dandy and fashion leader, famous for his elegant dress, his witty remarks and his friendship with George, Prince of Wales, the future George IV.

From Downing Street to Eton

George Bryan Brummell, famously nicknamed “Beau”, was born on 7 June 1778, the younger son of Billy Brummell and Mary Richardson. He was born in Downing Street, where his father worked as private secretary to Lord North. In 1783, Billy Brummell retired from politics and bought an estate, Donnington Grove in Berkshire.

In 1786, Brummell was sent to Eton with his elder brother, William. They were Oppidans or fee-paying boys and boarded with Dame Young. Brummell mingled with the aristocracy, becoming known for his gentlemanly manners and ready wit, which kept him out of trouble. He developed an interest in dress and his elegant bearing earned him the nickname Buck Brummell.

A grand inheritance

When Brummell’s father died in 1794, he left his estate to be shared equally between his three children, rather than the whole going to his eldest son. The estate, valued at around £60,000, was to be held in trust until the children came of age. This was a huge fortune, equivalent to more than £5 million today using the retail price index, and more like £70 million when relative earnings are taken into account.(1)

The Hussars

Brummell went up to Oriel College, Oxford, in May 1794, but after just one term, he asked his father’s executors for a commission in the army. He became a cornet in the 10th Light Dragoons – the

Prince of Wales’ own regiment. The dragoons wore elaborate uniforms and liked to be known as Hussars. They were disorderly, hard drinking and known for their lack of morality, and included many of the Prince of Wales’ set, of which Brummell soon became an important member.

Brummell obtained promotion to lieutenant in 1795 and then captain in 1796, and with each promotion came a new, and grander, uniform. But life in the army had its costs. A fall, or possibly a kick, from his horse broke his nose, damaging his classic profile.

Brummell and the Prince

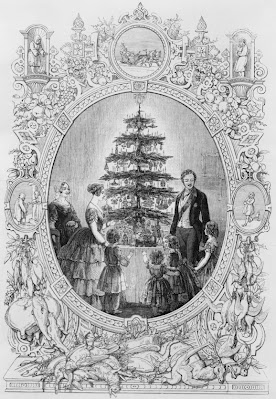

|

George, Prince of Wales

from Memoirs of George IV

by Robert Huish (1830) |

It seems incredible that a non-aristocratic boy of sixteen should be accepted into the Prince’s own regiment and then into his circle of intimate friends. How Brummell first came to the Prince’s notice is not known, but it seems likely that it was his wit and dress sense that attracted the Prince, probably while Brummell was still at Eton.

Brummell supported the Prince at his

wedding to Princess Caroline in 1795; he was also one of the drunken companions whom she accused of ruining her honeymoon.

When the regiment were ordered to Manchester in 1798, Brummell sold out, anxious not to lose his position of influence with the Prince. The following year, he came into his inheritance. He was now a man of means and meant to make his mark.

Beau Brummell the dandy

Brummell moved into 4 Chesterfield Street in 1799 and determined to become the best dressed gentleman in London. His levées became events of great importance as gentlemen, including the Prince of Wales, came to see how he dressed. It was around 1800, after Brummell’s first season in London, that he acquired the nickname Beau.

His style was understated elegance, with a limited palette of colours, rather than the gaudy finery of the Georgian gentleman. He was famous for the intricate folds of his neck cloth and the Bath coating material of his blue jacket. He patronized a variety of tailors so that no one could say that they made him famous.

Brummell rules the ton

For many years, it was Brummell’s opinion that mattered. It was he who influenced who should be given vouchers for

Almack’s. He could bring someone into fashion by showing them favour or put someone out of fashion by cutting them.

He was a member of Whites, Brooks and Watiers. A bow window in his club at White’s became known as the Beau window because that was where Brummell liked to sit. He was the perpetual president of Watiers which was established to provide better suppers to the gentlemen who ate in their clubs.

|

The bow window at White's

from The History of White's

by Hon Algernon Bourke (1892) |

Brummell’s lady friends

Though he flirted prolifically, Brummell’s affections were rarely engaged. Brummel’s first love was reputedly Julia Storer, later Julia Johnstone, who became a famous courtesan.

He was particular friends with Lady Hester Stanhope, the eccentric bluestocking; Lady Elizabeth Howard, Duchess of Rutland, until his rudeness alienated her; and the

Duchess of Devonshire who wrote poems for his collection.

But his closest lady friend was

Frederica, Duchess of York. He loved her unstructured house parties at Oatlands and shared her love of animals. He gave her a dog, Fidélité; she sent him gifts in exile, including a comfy chair. One of the few items in Brummell’s possession at his death was a miniature of Princess Frederica’s left eye. This suggests a level of intimacy that can only be guessed at. Brummell claimed it was out of respect for promises to the Princess that he refused to publish his memoirs even when he was desperate for money.

|

Frederica, Duchess of York

from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick,

Duke of York and Albany

by John Watkins (1827) |

Brummell’s downfall

Brummell was famous for his wit, but infamous for his rudeness. It was this rudeness which eventually cost him the Prince of Wales’ regard. “Alvanley, who’s your fat friend?”(2) he asked, referring to the Prince.

Brummell ran up debts through his extravagance, but also through his heavy gambling losses. He was continually borrowing money, but matters came to a head when a man named Richard Meyler discovered that Brummell was going to renege on his debt to him. He sat in White’s and told all who came of Brummell’s infamous conduct. He was, effectively, asking him out. Meyler became known as Dick the Dandy-killer.

Escape to Calais

On the night of 16 May 1816, after attending the theatre, Brummell fled from London to escape his debts. He travelled through the night to Dover and on to Calais, which was as far as he could go without a passport. He stayed at Dessin’s Hotel and entertained in his apartments whilst learning French and writing his memoirs.

Brummell had escaped his debts, but he could not escape the reality that he was ill. He probably acquired the habit of visiting prostitutes whilst in the army, and at some point, late in his time in London, he was infected with syphilis.

Before he died in 1830, George IV made Brummell the British consul in Caen. The salary enabled him to start paying off the debts he had already accumulated in Calais. He celebrated his freedom in Paris before taking up his post.

Consul in Caen

In Caen, he lodged with Madame de St Ursain and fell in love with her teenage daughter, Aimable. By now, he was suffering from terrible headaches and depression from the progression of his illness.

But his position as consul did not last and when the post was abolished in 1832, his debts became pressing and he had to hide to escape the bailiffs.

That summer, Brummell suffered a temporary paralysis. His letters to Aimable were discovered and her furious mother evicted him from his lodgings. When she was sent to England, Brummell gave her his album – poems that he had collected from his friends.

|

Brummell as an old man

from The History of White's

by Hon Algernon Bourke (1892) |

Decline and death

On 4 May 1835, Brummell was arrested for the money he owed to Leleux, the owner of Dessin’s Hotel in Calais. George Armstrong, a Caen grocer, agreed to travel to England to seek pecuniary help on Brummell’s behalf. Brummell was awarded compensation for the loss of the consulship and was duly released from prison on 21 July 1835.

Brummell struggled on as the syphilis took its course. He was increasingly in pain, delusional, depressed and subject to seizures and eventually insanity. In January 1839, he was transferred to an asylum where he died on 30 March 1840. His death went virtually unnoticed in England where he had ruled as king of the ton for so long.

Read more about Beau Brummell -

30 quotes and anecdotes.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian historical romance set in the time of Jane Austen. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.

If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(2) From Jesse's The Life of George Brummell Volume I p273.

Sources used include:

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée (John Bell, 1806, 1810, London)

Bourke, Hon. Algernon, The History of White's (1892)

Carter, Philip, Brummell, George Bryan (Beau Brummell) (1778-1840), Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn Jan 2011, accessed 5 Oct 2012)

Huish, Robert, Memoirs of George IV (1830)

Jesse, William, The Life of George Brummell, esq., Commonly called Beau Brummell (Saunders & Otley, 1844, London)

Kelly, Ian, Beau Brummell, The Ultimate Dandy (Hodder & Stoughton, 2005)

Watkins, John, A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany (1827, London)

MeasuringWorth website - for calculators of relative worth

The best part about writing a blog is when people take the time to let you know that they have enjoyed what you have written. Last week, I was delighted to receive an email from Susan Ardelie, author of the Life Takes Lemons blog, thanking me for my blog and nominating me for the One Lovely Blog Award.

The best part about writing a blog is when people take the time to let you know that they have enjoyed what you have written. Last week, I was delighted to receive an email from Susan Ardelie, author of the Life Takes Lemons blog, thanking me for my blog and nominating me for the One Lovely Blog Award.