Princess Sophia (29 May 1773 - 29 November 1844) was the daughter of Prince William Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester, a younger brother of George III.

Family history

Princess Sophia Matilda was born in Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, on 29 May 1773, the eldest child and only surviving daughter of William Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester, a younger brother of George III, and his wife, Maria, the illegitimate daughter of Sir Edward Walpole MP and widow of the 2nd Earl Waldegrave.

Family history

Princess Sophia Matilda was born in Grosvenor Street, Mayfair, on 29 May 1773, the eldest child and only surviving daughter of William Henry, 1st Duke of Gloucester, a younger brother of George III, and his wife, Maria, the illegitimate daughter of Sir Edward Walpole MP and widow of the 2nd Earl Waldegrave.

Sophia’s parents had married in secret in 1766 and her father did not tell his brother the King about his marriage until they found that Maria was pregnant. George III was hurt by his brother’s deceitfulness and instigated an investigation into the validity of the marriage which was carried out just six days before Sophia was born.

According to The Gentleman’s Magazine, “the usual notice was sent to the King requesting he would direct the proper officers to attend the birth” but “no notice was taken of the message.”1 George III was so displeased with the marriage that he banned the Duke of Gloucester and his family from the royal presence.

According to The Gentleman’s Magazine, “the usual notice was sent to the King requesting he would direct the proper officers to attend the birth” but “no notice was taken of the message.”1 George III was so displeased with the marriage that he banned the Duke of Gloucester and his family from the royal presence.

Sophia was christened privately on 26 June 1773 at Gloucester House by David Moss, Lord Bishop of St David’s and Rector of St George’s, Hanover Square. According to The Gentleman’s Magazine, her sponsors were “the Princess Amelia in person and their Royal Highnesses the Duke and Duchess of Cumberland.”1

Continental living

The Duke and Duchess and their daughter spent many years abroad for reasons of economy and for the sake of the Duke’s health. He suffered repeated bouts of a debilitating illness with symptoms not dissimilar to those later suffered by his brother George III. Sophia’s brother William was born in Rome in 1776 and the family returned to England the following year, but were abroad again for most of the period from 1784 to 1787. In time, the King became reconciled to the Duke, but not to the Duke’s marriage.

Royal provision

In 1778, at the King’s request, parliament made provision for the Duke’s children, by which Sophia was awarded a grant of £4000 a year after her father’s death.

George III also arranged for a Miss Dee to be governess to Sophia and her brother William.

Debut

Sophia made her debut at the King’s birthday in 1790, accompanied by her brother and her governess-companion, Miss Dee. According to Charlotte Keppel, Sophia was not treated very well. She and William were not invited to the dinner before the ball as they had expected and had to wait around for the ball to start. Sophia was “not dressed well in a very old fashioned style – her gown was very magnificent but the hair was dressed quite out of fashion.” She “danced very well but nobody paid her the least respect, and after the King and Queen were gone she was treated quite as a common person and pushed about.”2

Royal provision

In 1778, at the King’s request, parliament made provision for the Duke’s children, by which Sophia was awarded a grant of £4000 a year after her father’s death.

George III also arranged for a Miss Dee to be governess to Sophia and her brother William.

Debut

Sophia made her debut at the King’s birthday in 1790, accompanied by her brother and her governess-companion, Miss Dee. According to Charlotte Keppel, Sophia was not treated very well. She and William were not invited to the dinner before the ball as they had expected and had to wait around for the ball to start. Sophia was “not dressed well in a very old fashioned style – her gown was very magnificent but the hair was dressed quite out of fashion.” She “danced very well but nobody paid her the least respect, and after the King and Queen were gone she was treated quite as a common person and pushed about.”2

Noble modesty

According to her profile in La Belle Assemblée:

Her Royal Highness the Princess Sophia of Gloucester has kept an equal pace with her Royal cousins in the cultivation of every virtue and feminine accomplishment; she is to be distinguished for the same noble modesty of demeanour, the same benevolence and affability, the same preference of retirement and domestic life.3Fanny Burney described Princess Sophia in her diary:

She is very fat, with very fine eyes, a bright, even dazzling bloom, fine teeth, a beautiful skin, and a look of extreme modesty and sweetness.4

Sophia’s father owned a house in Weymouth, Gloucester Lodge, which the King used for his visits to the seaside from 1789 onwards. During the royal family’s visit of August to October 1804, Sophia and her father were of the party. The Gentleman’s Magazine records that on the 8 September, they travelled to Bincomb Downs where they watched “a grand review and sham fight between all the regiments.”5

|

| Gloucester Lodge, the Duke of Gloucester's house, Weymouth seafront (2012) |

In 1813, Sophia was appointed Ranger of Greenwich Park and Ranger’s House was altered to provide her with suitable accommodation. She was very popular with the people of Greenwich who saw her as a kind and generous benefactor to the town’s poor.

Devotion to William

|

| William Frederick, Duke of Gloucester from A Biographical Memoir of Frederick, Duke of York and Albany by John Watkins (1827) |

Sophia never married nor had any children, but she was excessively fond of her brother. After his marriage to Princess Mary in 1816, she was a frequent visitor to their home, Bagshot Park, but her sister-in-law resented her interfering behaviour which did not promote domestic harmony. When William died quite suddenly in 1834, Sophia was devastated. Princess Mary made sure that Sophia was not her constant companion in her widowhood.

The final years

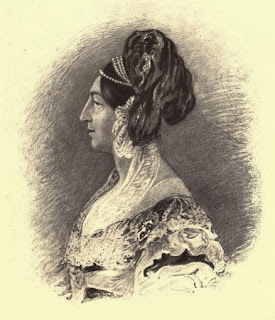

|

| Princess Sophia Matilda of Gloucester from from The Girlhood of Queen Victoria (1912) |

Sophia died at Blackheath, Kent, on 29 November 1844 and was buried in St George’s Chapel, Windsor.

Rachel Knowles writes clean/Christian Regency era romance and historical non-fiction. She has been sharing her research on this blog since 2011. Rachel lives in the beautiful Georgian seaside town of Weymouth, Dorset, on the south coast of England, with her husband, Andrew.

Find out more about Rachel's books and sign up for her newsletter here.If you have enjoyed this blog and want to encourage me and help me to keep making my research freely available, please buy me a virtual cup of coffee by clicking the button below.

Notes

(1) From The Gentleman’s Magazine (May 1773).

(2) From a letter by Charlotte Keppel to Anne Clement (June 1790) in Princesses by Flora Fraser.

(3) From La Belle Assemblée (1806).

(4) From The Diaries and Letters of Madame D’Arblay, Volume 3 of 3 (1846).

(5) From The Gentleman’s Magazine (Supp 1804)

Sources used include:

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée (John Bell, 1806)

Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett, volume III (Henry Colburn, 1846, London)

Fraser, Flora, Princesses, the six daughters of George III (2004)

The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle (1773-1804)

Victoria, Queen, The Girlhood of Queen Victoria, A Selection from Her Majesty's Diaries between the years 1832 and 1840, edited Viscount Esher 2 Volumes (1912)

Royal Borough of Greenwich website

All photographs by © RegencyHistory.net

(1) From The Gentleman’s Magazine (May 1773).

(2) From a letter by Charlotte Keppel to Anne Clement (June 1790) in Princesses by Flora Fraser.

(3) From La Belle Assemblée (1806).

(4) From The Diaries and Letters of Madame D’Arblay, Volume 3 of 3 (1846).

(5) From The Gentleman’s Magazine (Supp 1804)

Sources used include:

Bell, John, La Belle Assemblée (John Bell, 1806)

Burney, Fanny, Diary and letters of Madame D'Arblay, edited by her niece, Charlotte Barrett, volume III (Henry Colburn, 1846, London)

Fraser, Flora, Princesses, the six daughters of George III (2004)

The Gentleman's Magazine and Historical Chronicle (1773-1804)

Victoria, Queen, The Girlhood of Queen Victoria, A Selection from Her Majesty's Diaries between the years 1832 and 1840, edited Viscount Esher 2 Volumes (1912)

Royal Borough of Greenwich website

All photographs by © RegencyHistory.net